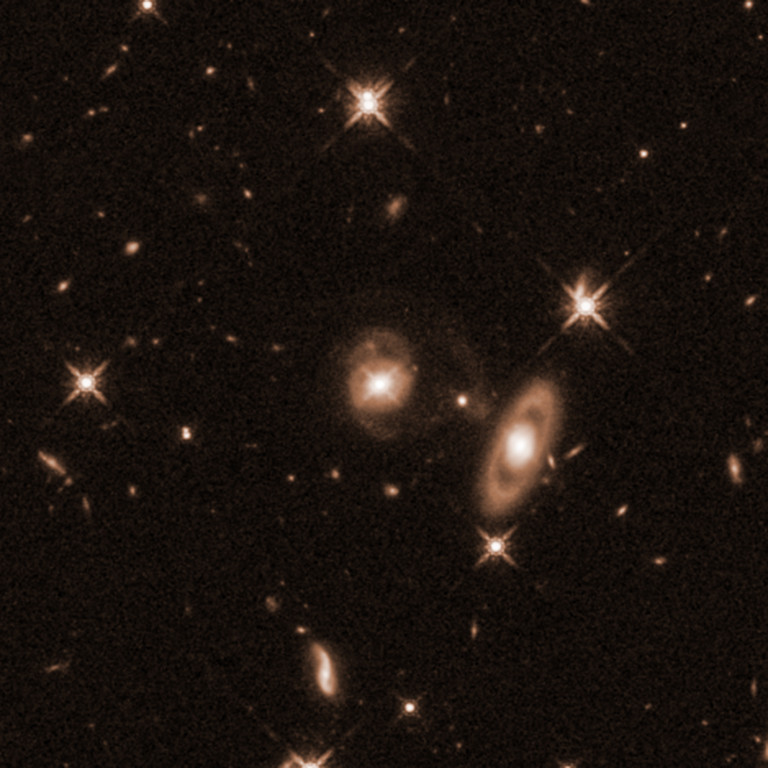

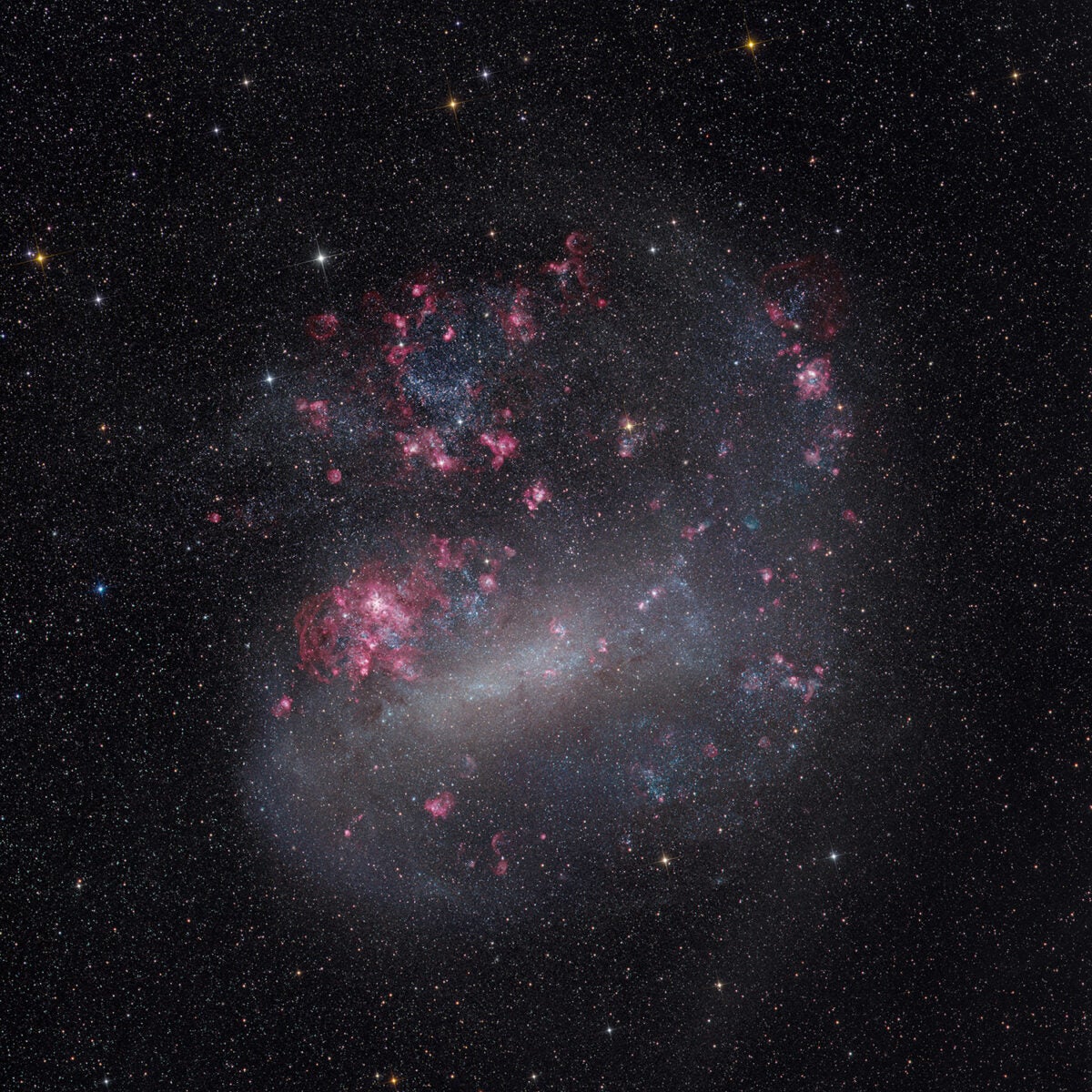

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) is one of the Milky Way’s closest neighbors. It’s a small, irregular galaxy that orbits the Milky Way, and is an easy naked-eye object from the Southern Hemisphere. As one of the only galaxies outside our own where telescopes can resolve individual stars and small scale structures, astronomers love to examine the LMC to compare and contrast it with the Milky Way.

While large galaxies host central supermassive black holes (SMBH) as a rule, dwarf galaxies like the LMC are more mixed. Astronomers have speculated about it containing a black hole, but the data has been inconclusive.

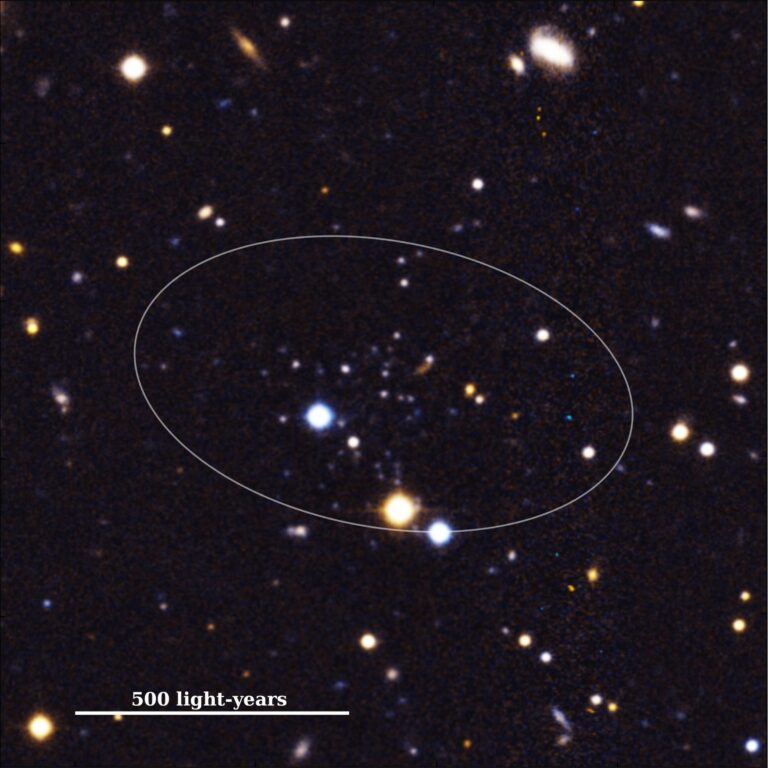

Now, data from the Gaia space telescope, which tracked more than a billion stars to measure their movements and positions, has pointed to a surprising addition to this object that sits right in our cosmic backyard: It appears to have a central black hole weighing 600,000 times as much as the Sun. The research, led by Jesse Jiwon Han of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Speedy stars

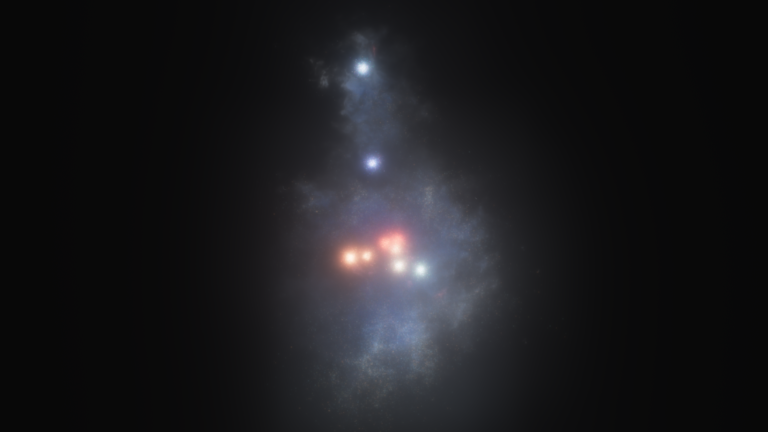

The discovery comes from a study of hypervelocity stars in the Milky Way. These are stars that, as their name indicates, are moving rapidly compared to their neighbors — up to 2.2 million miles per hour (1,000 kilometers per second), instead of cruising along with the rest of the stars in the current of the Milky Way. Astronomers thought that most of these hypervelocity stars reached those high speeds after an encounter with the Milky Way’s own central black hole, Sagittarius A*. (Such speedy stars were one of the biggest clues that led astronomers to discover and understand Sag A*.)

But when Han, a graduate student at the CfA, looked at a batch of hypervelocity stars in the Gaia data, he tracked their path back not toward the Milky Way’s core, but to the LMC.

There aren’t many things that can accelerate a star to such high speeds. A star exploding in a supernovae or being ejected from a tight cluster of stars are a couple ways. Close encounters with a black hole are another. Usually black holes can “kick” a star to higher speeds than the other methods, but there aren’t clear cutoffs.

What stood out to Han and colleagues wasn’t just the speed of the stars, high even for hypervelocity stars — it was the way they clustered on the sky, in one tight group, dubbed the Leo Overdensity because it lies within the boundaries of the constellation Leo. That gave the team the big clue they needed to figure out the stars’ origins.

“Since these stars are young and massive,” Han told Astronomy, “They have to come from either the disk or the center of the LMC — those are the only two options.” And if they come from the disk, Han says, models show that the stars would be spread out across a bigger chunk of the sky. “That is to say, only an ejection from the center of the LMC can produce an overdensity as tight as the Leo Overdensity.”

Xavier Luri, an astrophysicist at the University of Barcelona and a member of the Gaia data processing consortium who was not involved with the study, called Han’s work “very complete and thorough … The conclusions are based on a number of assumptions and hypotheses that can still be questioned in the future, but overall they consistently point to an origin of a part of the sample linked to an LMC central black hole.”

The Leo Overdensity has been observed for a long time. In fact, in 2016, astronomers Douglas Boubert and Wyn Evans from the University of Cambridge, U.K., even proposed an SMBH in the LMC as the culprit. But it took until now, with the precise data from Gaia, to trace enough hypervelocity stars to their source to make the argument sound.

“Using the latest data from Gaia, Jesse and his stellar team of co-authors have proven [our] outlandish theory,” says Boubert. “Half of the hypervelocity stars we know of in the Northern Hemisphere also come from the Large Magellanic Cloud.”

Surprising find

Astronomers have known for a while now that every major galaxy contains a central SMBH. What’s more, the size of the black hole scales quite predictably with the size of the galaxy, a characteristic astronomers call the M-sigma relationship. But dwarf galaxies don’t always follow this rule, and the LMC wasn’t known to have a black hole. If confirmed, this black hole would mark a big change in how astronomers understand our small neighbor’s structure and evolution.

On the other hand, Han’s team can measure how massive a black hole would need to be to eject stars at the measured velocities, and they calculate it would be roughly 600,000 solar masses. That turns out to fit perfectly into the expected M-sigma relationship, given what we know about the LMC’s overall mass.

Han says, “So, while it’s rather surprising how we found evidence for the SMBH, the actual mass of the SMBH is totally within reason, and should’ve been somewhat expected.”

Looking ahead

Now that there are solid clues for the LMC’s SMBH, astronomers will surely look to confirm its existence. Common ways to look for black holes include looking for X-ray and radio signals, which splash out from the vicinity of black holes as material falls in. Or, astronomers could look for more direct dynamical clues, like star clusters moving around an invisible central mass.

Moreover, the data Han and his team used is from only the first three years of Gaia data. A more complete data release is scheduled for 2026, and the full 10 years of the observatory’s data will be available at the end of the decade. That will give astronomers everywhere more data for examining how stars move about, both in our galaxy and in the LMC.

Boubert says that by proving the existence of the LMC’s SMBH, “Jesse and team lay down a gauntlet to astronomers to find the rest of the hypervelocity star stream from the Large Magellanic Cloud. Once found, this population of hypervelocity stars will transform our understanding of the dynamics and history of our local galactic neighborhood — knowing both the locations and speeds of stars in the present-day and where they were born places incredibly tight constraints on the dance of the Milky Way and Large Magellanic Cloud over the last several hundred million years.”