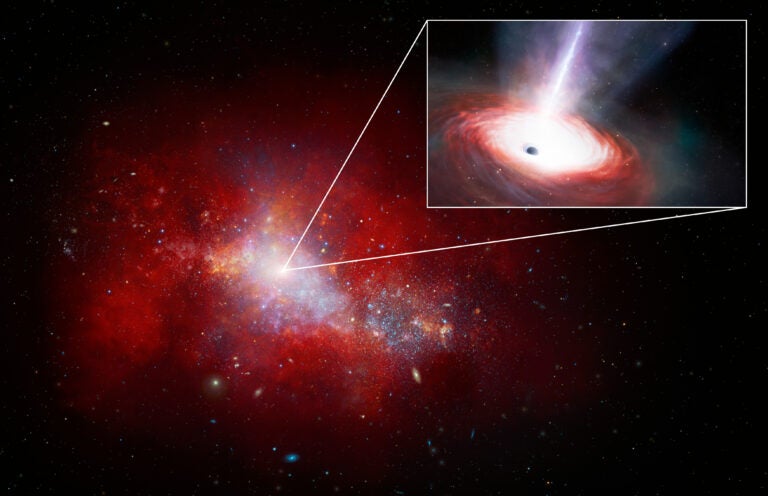

Massive galaxies harbor black holes with millions of times more mass than our Sun at their centers. When two such galaxies collide, their supermassive black holes join in a close orbital dance that ultimately results in the pair combining. That process, scientists expect, is the strongest source of the long-sought, elusive gravitational waves, still yet to be directly detected.

“Gravitational waves represent the next great frontier in astrophysics, and their detection will lead to new insights on the universe,” said David Roberts of Brandeis University. “It’s important to have as much information as possible about the sources of these waves,” he added.

Astronomers worldwide have begun programs to monitor fast-rotating pulsars throughout our Milky Way Galaxy in an attempt to detect gravitational waves. These programs seek to measure shifts in the signals from the pulsars caused by gravitational waves distorting the fabric of space-time. Pulsars are spinning superdense neutron stars that emit lighthouse-like beams of light and radio waves that allow precise measurement of their rotation rates.

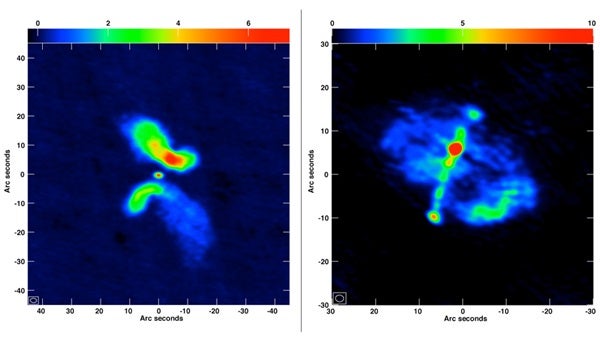

Roberts and his colleagues studied a sample of galaxies called “X-shaped radio galaxies,” whose peculiar structure indicated the possibility that the radio-emitting jets of superfast particles ejected by disks of material swirling around the central black holes of these galaxies have changed directions. The change, astronomers suggested, was caused by an earlier merger with another galaxy, causing the spin axis of the black hole as well as the jet axis to shift direction.

Working from an earlier list of 100 such objects, they collected archival data from the VLA to make new, more detailed images of 52 of them. Their analysis of the new images led them to conclude that only 11 are “genuine” candidates for galaxies that have merged, causing their radio jets to change direction. The jet changes in the other galaxies, they concluded, came from other causes.

Extrapolating from this result, the astronomers estimated that fewer than 1.3 percent of galaxies with extended radio emission have experienced mergers. This rate is five times lower than previous estimates.

“This could significantly lower the level of very-long-wave gravitational waves coming from X-shaped radio galaxies, compared to earlier estimates,” Roberts said. “It will be very important to relate gravitational waves to objects we see through electromagnetic radiation, such as radio waves, in order to advance our understanding of fundamental physics.”

Gravitational waves, ripples in space-time, were predicted in 1916 by Albert Einstein as part of his theory of general relativity. The first evidence for such waves came from observations of a pulsar orbiting another star, a system discovered in 1974 by Joseph Taylor and Russell Hulse. Observations of this pair over several years showed that their orbits are decaying at exactly the rate predicted by Einstein’s equations that indicate gravitational waves carrying energy away from the system.

Taylor and Hulse received the 1993 Nobel Prize in physics for this work, which confirmed a predicted effect of gravitational waves. However, no direct detection of such waves has yet been made.

Roberts worked with Jake Cohen and Jing Lu from Brandeis, who retrieved the data from the VLA archive and produced the images of the galaxies, and Lakshmi Saripalli and Ravi Subrahmanyan of the Raman research Institute in Bangalore, India.