Remember that cry of excitement when you recognized those seven stars for the first time? It could have been decades ago, or maybe just last night. Either way, the Dipper quickly became a lifelong friend. It’s there every clear night throughout the year to greet us as we venture out into the universe.

Beginners come to know the Big Dipper as a handy signpost for finding other stars in the sky — “Follow the Pointers to Polaris” or “Arc to Arcturus.” This month, we’ll use some of the Dipper’s visual cues to hunt down binocular targets in the area north and west of the Dipper’s bowl. Next month, in “Big Dipper, part two,” we’ll use its crooked handle to discover other binocular-friendly targets.

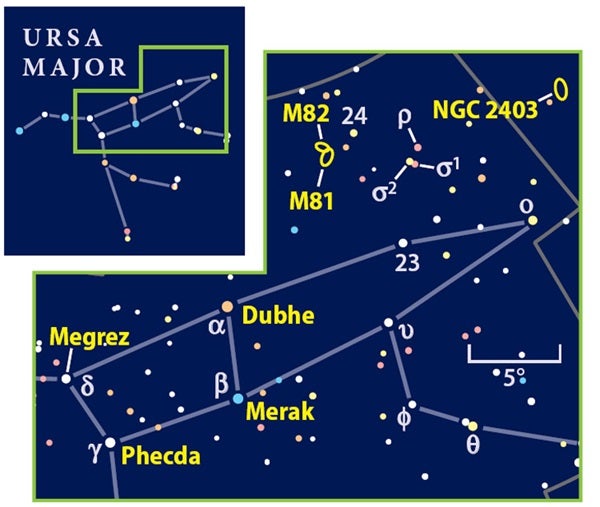

Let’s first examine each of the four stars that make up the bowl: Dubhe, Merak, Phecda, and Megrez. All shine nearly white, except for Dubhe at the bowl’s northwest corner, which radiates an orangish glow. That’s no surprise because Dubhe is an orange, type-K giant star — larger but cooler than our own Sun.

Using your imagination, draw a line from Phecda, at the bowl’s southeastern corner, to Dubhe. Extend that line an equal distance to the northwest until you come to a small right triangle of stars. The star marking the right angle itself is cataloged as 24 Ursa Majoris, while most star charts don’t name the other stars.

If you look carefully, you just might spot a faint blur to the triangle’s southeast. That’s no star but rather the distant spiral galaxy M81. Admittedly, finding M81 can be daunting at first, but, give it a chance, and you’re bound to spot it.

Look just north of M81, and try to make out a dimmer splinter of grayish light. If so, you have found M82, a dramatic irregular galaxy shown in long-exposure photographs to be erupting from within. 7×35 binoculars also reveal this galaxy’s famous cigar shape, provided the night is dark. Unlike M81, however, which shows a brighter core, M82 appears uniformly dim from end to end.

M81 and M82 each lie about 12 million light-years from us, but about 100,000 light-years separate them. Together, they form one of the most striking galaxy pairs in the sky. Other galaxies belong to the M81/M82 group, but, unfortunately, all but one are too faint for our binoculars.

That visible member galaxy lies a good distance away, across the border within the faint constellation Camelopardalis. Comet-hunter Charles Messier (1730–1817) and his contemporaries never saw this spectacular spiral galaxy even though it shines as brightly as M82. With no M classification, it’s known today as NGC 2403, its entry in the New General Catalog.

Hunting down NGC 2403 can be tough, but here’s how I do it. Start at M81, and move about 1 binocular field southwest, to a slender triangle formed by 5th-magnitude stars Rho (ρ), Sigma1 (σ1), and Sigma2 (σ2) Ursae Majoris. This distinctive triangle points toward the west-northwest, right at a lone 5th-magnitude star about a field away. From there, jog another binocular field southwest to a larger right triangle of three 6th-magnitude stars. Our target lies halfway between the triangle’s right angle and its southern corner.

Recently, I visited NGC 2403 through my 10×50 binoculars. I just made out its tiny oval glow against the background sky from my backyard here on Long Island. It’s a challenging test, but now is the best time of year to give it a go in the evening sky — it crests near our zenith.

Try your luck with each of these three galaxies on the next clear night, and then drop me a line here to let me know how you did. And be sure to visit Astronomy.com this month, where I list a few more challenges in Ursa Major.