New images from the European Space Agency’s Planck space observatory reveal the forces driving star formation and give astronomers a way to understand the complex physics that shape the dust and gas in our galaxy.

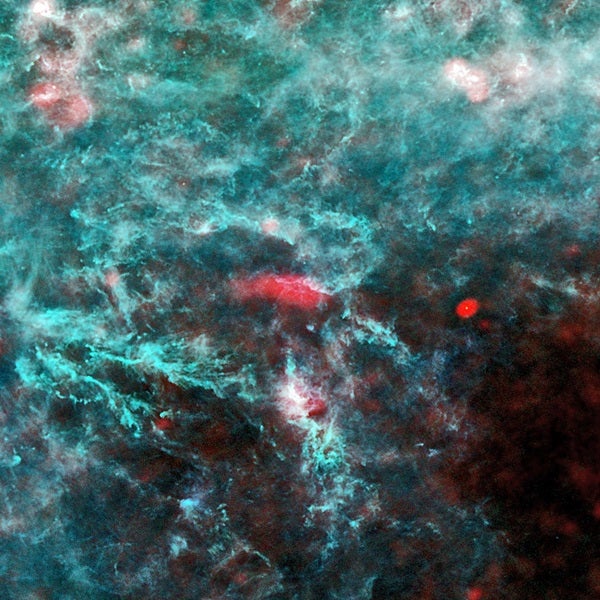

Star formation takes place hidden behind veils of dust but that doesn’t mean we can’t see through them. Where optical telescopes see only black space, Planck’s microwave eyes reveal myriad glowing structures of dust and gas. Now, Planck has used this ability to probe two relatively nearby star-forming regions in our galaxy.

The Orion region is a cradle of star formation, some 1,500 light-years away. It is famous for the Orion Nebula, which can be seen by the naked eye as a faint smudge.

The first image covers much of the constellation of Orion. The nebula is the bright spot to the lower center. The bright spot to the right of center is around the Horsehead Nebula.

The giant red arc of Barnard’s Loop is thought to be the blast wave from a star that blew up inside the region about 2 million years ago. The bubble it created is now about 300 light-years across.

The images both show three physical processes taking place in the dust and gas of the interstellar medium. Planck can show us each process separately. At the lowest frequencies, Planck maps emission caused by high-speed electrons interacting with the galaxy’s magnetic fields. An additional diffuse component comes from spinning dust particles emitting at these frequencies.

At intermediate wavelengths of a few millimeters, the emission is from gas heated by newly formed hot stars.

At still higher frequencies, Planck maps the meager heat given out by extremely cold dust. This can reveal the coldest cores in the clouds, which are approaching the final stages of collapse, before they are reborn as fully fledged stars. The stars then disperse the surrounding clouds.

The delicate balance between cloud collapse and dispersion regulates the number of stars that the galaxy makes. Planck will advance our understanding of this interplay because, for the first time, it provides data on several major emission mechanisms in one go.

Planck’s primary mission is to observe the entire sky at microwave wavelengths in order to map the variations in the ancient radiation given out by the Big Bang. Thus, it cannot help but observe the Milky Way as it rotates and sweeps its electronic detectors across the night sky.