The Planck mission released a new data catalog Tuesday from initial maps of the entire sky. The catalog includes thousands of never-before-seen dusty cocoons where stars are forming and some of the most massive clusters of galaxies ever observed. Planck is a European Space Agency (ESA) mission with significant contributions from NASA.

“NASA is pleased to support this important mission, and we have eagerly awaited Planck’s first discoveries,” said Jon Morse, NASA’s Astrophysics Division director at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. “We look forward to continued collaboration with ESA and more outstanding science to come.”

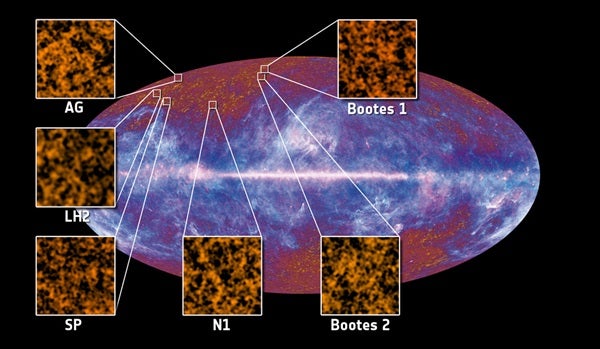

Planck launched in May 2009 on a mission to detect light from just a few hundred thousand years after the Big Bang, an explosive event at the dawn of the universe approximately 13.7 billion years ago. The spacecraft’s state-of-the-art detectors ultimately will survey the whole sky at least four times, measuring the cosmic microwave background (CMB), or radiation left over from the Big Bang. The data will help scientists decipher clues about the evolution, fate, and fabric of our universe. While these cosmology results won’t be ready for another 2 years or so, early observations of specific objects in our Milky Way Galaxy, as well as more distant galaxies, are being released.

“The data we’re releasing now are from what lies between us and the cosmic microwave background,” said Charles Lawrence, the U.S. project scientist for Planck at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We ultimately will subtract these data out to get at our cosmic microwave background signal. But by themselves, these early observations offer up new information about objects in our universe — both close and far away, and everything in between.”

Planck observes the sky at nine wavelengths of light, ranging from infrared to radio waves. Its technology has greatly improved sensitivity and resolution over its predecessor missions, NASA’s Cosmic Background Explorer and Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe.

The result is a windfall of data on known and never-before-seen cosmic objects. Planck has cataloged approximately 10,000 star-forming “cold cores,” thousands of which are newly discovered. The cores are dark and dusty nurseries where baby stars are just beginning to take shape.

They also are some of the coldest places in the universe. Planck’s new catalog includes some of the coldest cores ever seen, with temperatures as low as 7 degrees above absolute zero, or –447° Fahrenheit. In order to see the coldest gas and dust in the Milky Way, Planck’s detectors were chilled to only 0.1 kelvin.

The new catalog also contains some of the most massive clusters of galaxies known, including a handful of newfound ones. The most massive of these holds the equivalent of a million billion suns worth of mass, making it one of the most massive galaxy clusters known.

Galaxies in our universe are bound together into these larger clusters, forming a lumpy network across the cosmos. Scientists study the clusters to learn more about the evolution of galaxies, dark matter, and dark energy — the exotic substances that constitute the majority of our universe.

“Because Planck is observing the whole sky, it is giving us a comprehensive look at how all the smaller structures of the universe are connected to the whole,” said Jim Bartlett, a U.S. Planck team member at JPL and the Astroparticule et Cosmologie-Universite Paris Diderot in France.

Planck’s new catalog also includes unique data on the pools of hot gas that permeate roughly 14,000 smaller clusters of galaxies; the best data yet on the cosmic infrared background, which is made up of light from stars evolving in the early universe; and new observations of extremely energetic galaxies spewing radio jets. The catalog covers about one and a half sky scans.

The Planck mission released a new data catalog Tuesday from initial maps of the entire sky. The catalog includes thousands of never-before-seen dusty cocoons where stars are forming and some of the most massive clusters of galaxies ever observed. Planck is a European Space Agency (ESA) mission with significant contributions from NASA.

“NASA is pleased to support this important mission, and we have eagerly awaited Planck’s first discoveries,” said Jon Morse, NASA’s Astrophysics Division director at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. “We look forward to continued collaboration with ESA and more outstanding science to come.”

Planck launched in May 2009 on a mission to detect light from just a few hundred thousand years after the Big Bang, an explosive event at the dawn of the universe approximately 13.7 billion years ago. The spacecraft’s state-of-the-art detectors ultimately will survey the whole sky at least four times, measuring the cosmic microwave background (CMB), or radiation left over from the Big Bang. The data will help scientists decipher clues about the evolution, fate, and fabric of our universe. While these cosmology results won’t be ready for another 2 years or so, early observations of specific objects in our Milky Way Galaxy, as well as more distant galaxies, are being released.

“The data we’re releasing now are from what lies between us and the cosmic microwave background,” said Charles Lawrence, the U.S. project scientist for Planck at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We ultimately will subtract these data out to get at our cosmic microwave background signal. But by themselves, these early observations offer up new information about objects in our universe — both close and far away, and everything in between.”

Planck observes the sky at nine wavelengths of light, ranging from infrared to radio waves. Its technology has greatly improved sensitivity and resolution over its predecessor missions, NASA’s Cosmic Background Explorer and Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe.

The result is a windfall of data on known and never-before-seen cosmic objects. Planck has cataloged approximately 10,000 star-forming “cold cores,” thousands of which are newly discovered. The cores are dark and dusty nurseries where baby stars are just beginning to take shape.

They also are some of the coldest places in the universe. Planck’s new catalog includes some of the coldest cores ever seen, with temperatures as low as 7 degrees above absolute zero, or –447° Fahrenheit. In order to see the coldest gas and dust in the Milky Way, Planck’s detectors were chilled to only 0.1 kelvin.

The new catalog also contains some of the most massive clusters of galaxies known, including a handful of newfound ones. The most massive of these holds the equivalent of a million billion suns worth of mass, making it one of the most massive galaxy clusters known.

Galaxies in our universe are bound together into these larger clusters, forming a lumpy network across the cosmos. Scientists study the clusters to learn more about the evolution of galaxies, dark matter, and dark energy — the exotic substances that constitute the majority of our universe.

“Because Planck is observing the whole sky, it is giving us a comprehensive look at how all the smaller structures of the universe are connected to the whole,” said Jim Bartlett, a U.S. Planck team member at JPL and the Astroparticule et Cosmologie-Universite Paris Diderot in France.

Planck’s new catalog also includes unique data on the pools of hot gas that permeate roughly 14,000 smaller clusters of galaxies; the best data yet on the cosmic infrared background, which is made up of light from stars evolving in the early universe; and new observations of extremely energetic galaxies spewing radio jets. The catalog covers about one and a half sky scans.