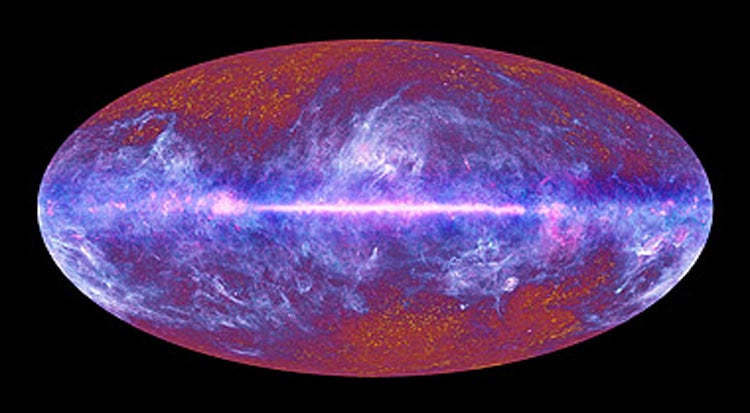

The microwave sky as seen by Planck.

ESA

July 6, 2010

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Planck mission has delivered its first all-sky image. It not only provides new insight into the way stars and galaxies form, but also tell us how the universe itself came to life after the Big Bang.

“This is the moment that Planck was conceived for,” said David Southwood, director of science and robotic exploration at ESA. “We’re not giving the answer. We are opening the door to an Eldorado where scientists can seek the nuggets that will lead to deeper understanding of how our universe came to be and how it works now. The image itself and its remarkable quality is a tribute to the engineers who built and have operated Planck. Now the scientific harvest must begin.”

From the closest portions of the Milky Way to the farthest reaches of space and time, the new all-sky Planck image is an extraordinary treasure chest of new data for astronomers. The main disk of our galaxy runs across the center of the image. Immediately striking are the streamers of cold dust reaching above and below the Milky Way. This galactic web is where new stars are being formed, and Planck has found many locations where individual stars are edging toward birth or just beginning their cycle of development.

Less spectacular, but perhaps more intriguing, is the mottled backdrop at the top and bottom. This is the “cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation.” It is the oldest light in the universe, the remains of the fireball out of which our universe sprang into existence 13.7 billion years ago.

While the Milky Way shows us what the local universe looks like now, those microwaves show us what the universe looked like close to its time of creation, before there were stars or galaxies. Here we come to the heart of Planck’s mission to decode what happened in that primordial universe from the pattern of the mottled backdrop.

The microwave pattern is the cosmic blueprint from which today’s clusters and superclusters of galaxies were built. The different colors represent minute differences in the temperature and density of matter across the sky. Somehow these small irregularities evolved into denser regions that became the galaxies of today.

The CMB covers the entire sky, but most of it is hidden in this image by the Milky Way’s emission, which must be digitally removed from the final data in order to see the microwave background in its entirety.

When this work is completed, Planck will show us the most precise picture of the microwave background ever obtained. The big question will be whether the data will reveal the cosmic signature of the primordial period called inflation. This era is postulated to have taken place just after the Big Bang and resulted in the universe expanding enormously in size over an extremely short period.

Planck continues to map the universe. By the end of its mission in 2012, it will have completed four all-sky scans. The first full data release of the CMB is planned for 2012. Before then, the catalog containing individual objects in our galaxy and whole distant galaxies will be released January 2011.

“This image is just a glimpse of what Planck will ultimately see,” said Jan Tauber, project scientist at ESA.