“These two worlds are having close encounters,” said Josh Carter from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“They are the closest to each other of any planetary system we’ve found,” said Eric Agol of the University of Washington in Seattle.

Scientists spotted the planets in data from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, which can detect a planet when it passes in front of, and briefly reduces the light coming from, its parent star.

The newfound system contains two planets circling a subgiant star much like the Sun, except several billion years older. The inner world, Kepler-36b, is a rocky planet 1.5 times the size of Earth that weighs 4.5 times as much. It orbits about every 14 days at an average distance of less than 11 million miles (18 million kilometers).

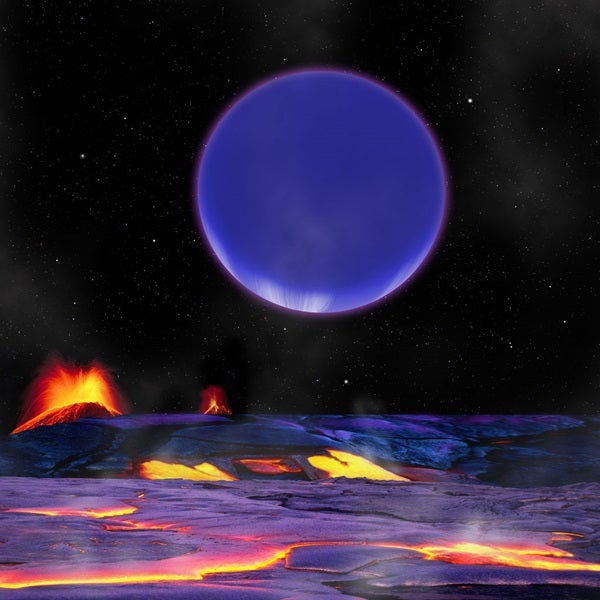

The outer world, Kepler-36c, is a gaseous planet 3.7 times the size of Earth that weighs eight times as much. This “hot Neptune” orbits once each 16 days at a distance of 12 million miles (19 million km).

The two planets experience a conjunction every 97 days, on average. At that time, they are separated by less than five Earth-Moon distances. Since Kepler-36c is much larger than the Moon, it presents a spectacular view in its neighbor’s sky. (Coincidentally, the smaller Kepler-36b would appear about the size of the Moon when viewed from Kepler-36c.) Such close approaches stir up tremendous gravitational tides that squeeze and stretch both planets.

Researchers are struggling to understand how these two different worlds ended up in such close orbits. Within our solar system, rocky planets reside close to the Sun while the gas giants remain distant.

Although Kepler-36 is the first planetary system found to experience such close encounters, it undoubtedly won’t be the last. “We’re wondering how many more like this are out there,” said Agol.

“We found this one on a first quick look,” said Carter. “We’re now combing through the Kepler data to try to locate more.”

This result was made possible with asteroseismology — the study of stars by observing their natural oscillations. Sun-like stars resonate like musical instruments due to sound waves trapped in their interiors. And just like a musical instrument, the larger the star, the “deeper” are its resonances. This trapped sound makes the stars gently breathe in and out, or oscillate.

“Kepler-36 shows beautiful oscillations,” said Bill Chaplin from the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. “By measuring the oscillations, we were able to measure the size, mass, and age of the star to exquisite precision. Without asteroseismology, it would not have been possible to place such tight constraints on the properties of the planets.”