In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, postcards were the social medium of choice, The period between 1907 and 1915 is now known as the Golden Age of Postcards. At its peak, it is estimated that the U.S. postal service mailed out over a billion one-penny postcards each year, many of which were printed in color. Often these postcards had astronomical themes such as great observatories or photographs of deep-sky and solar system objects — including comets.

Early beginnings

Patriotic covers were an early predecessor of the modern postcard. These were often posted during times of war. At the beginning of the Civil War, the Great Comet of 1861 (C/1861 J1) — also called the War Comet — blazed across the skies. At its peak, it had a magnitude between 0 and –2 and the tail spanned 90°, inspiring the production of a bizarre postal cover of a comet with the head of General Winfield Scott. Another version had Abraham Lincoln.

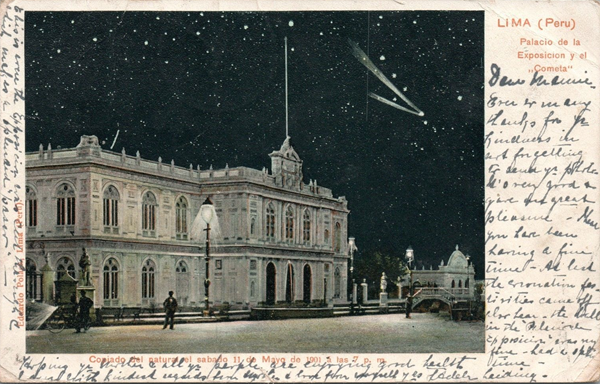

By the late 1890s, millions of postcards featuring drawings and photographs — many in color —were produced every year. One of these “new” picture postcards featured the Great Comet of 1901, also called Comet Viscara. Though primarily a Southern Hemisphere object, color postcards helped give it worldwide appeal.

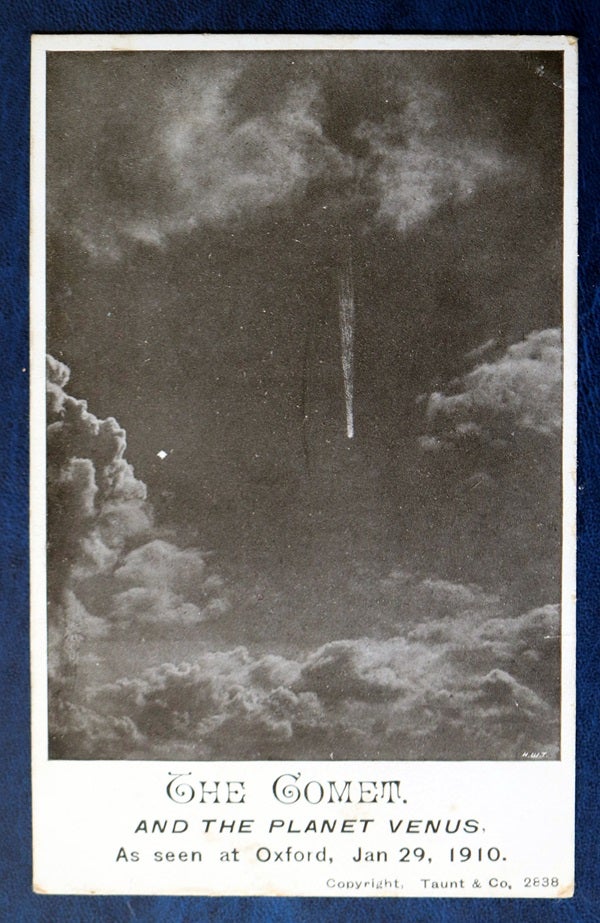

Comet C/1908 R1 (Morehouse) in 1908 was featured next, but the real show came in 1910, when two great comets blazed across the skies. The first was C/1910 A1 or the Great January Comet of 1910, sometimes referred to as the Daylight Comet. Likely discovered on Jan. 12, it quickly became a naked-eye object and by Jan. 17 was visible in daylight at magnitude–5, brighter than the planet Venus. It sported a broad 50° tail. A few beautiful postcards were produced, but were quickly overshadowed by the return of Halley’s Comet.

Through the tail

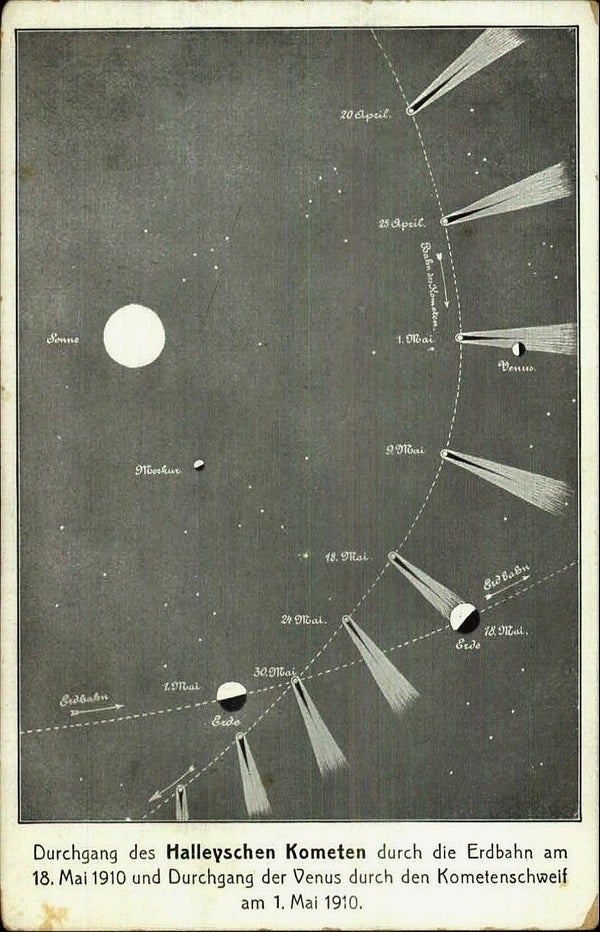

By far the most famous of all comets, 1P/ Halley has been observed continuously since 240 B.C. Based on its roughly 76-year period, its return in the spring of 1910 was predicted to be an especially good one. The sudden appearance of the Great January Comet several months before Halley’s perihelion on April 20 certainly helped to fire up the public’s expectations.

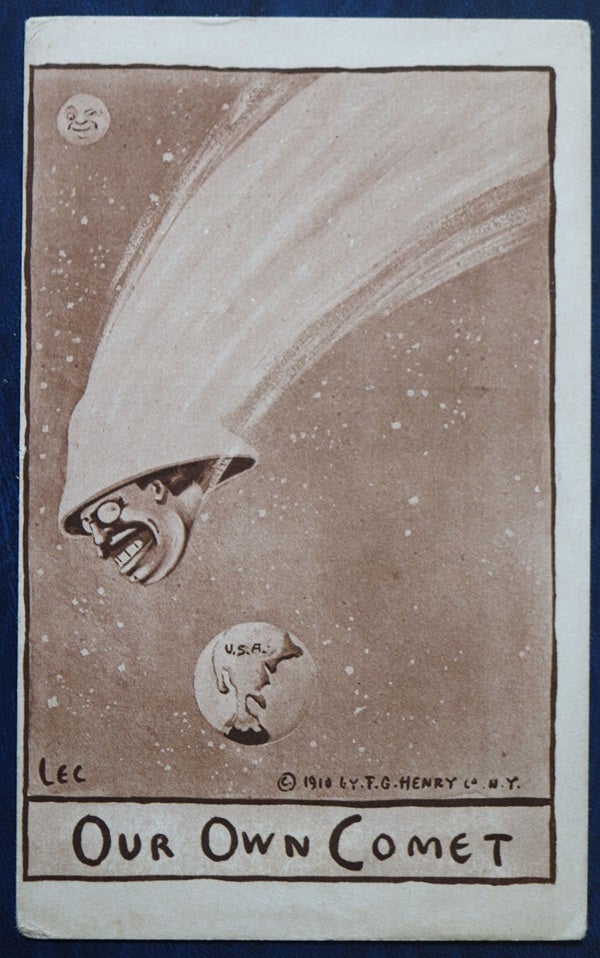

For thousands of years, comets have been seen as harbinger of change. So perhaps it’s big no surprise that Halley’s Comet was used to promote Teddy Roosevelt’s Progressive Party ticket.

The deadly gas cyanogen had just been discovered in the tail, and the passage led to worldwide panic. The famous French astronomer Camille Flammarion added fuel to the panic when The New York Times published his prediction that “cyanogen gas would impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet.” The truth was that Halley’s cyanogen was far too rarefied to be remotely a real threat — but panic still took hold. This led to products like comet pills, comet insurance, anti-comet umbrellas, and, of course, bizarre panic postcards. Of note is a French-produced series of strangely amusing cards depicting humanity desperately trying to evacuate the planet. On the other hand, German postcards of the event were purely whimsical in nature.

Yet other Halley postcard themes were more grounded in reality, showing the comet’s from main streets in America or from exotic vistas from around the world.

Comet mania lasted throughout the 1910s, with these ethereal objects appearing on holiday, greeting, and even advertising cards.

Calm before the storm

Over the next several decades, a series of brilliant comets graced the skies, though none inspired the same sort of comet mania seen in 1910.

That all changed March 7, 1973, when Luboš Kohoutek discovered a distant long-period comet. As a first-time visitor to the inner solar system, Comet C/1973 E1 (Kohoutek) was predicted to become the “comet of the century,” rivaling the planet Venus during Christmas 1973. But it failed to brighten as predicted and was considered a bust. It did become a naked-eye object with a tail 25° long, but never lived up to all the media hype. Still, several large observatories and even Skylab 4 took impressive images of the comet, which soon were featured on postcards and covers.

Halley’s return

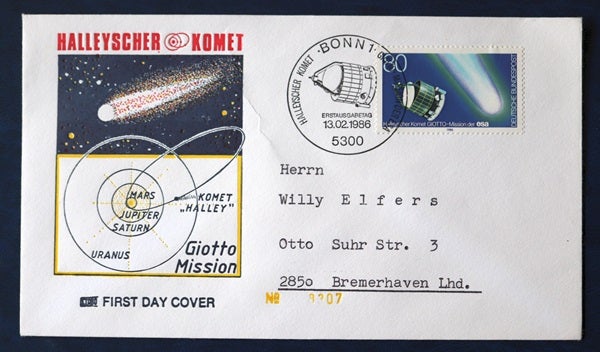

Unlike its appearance in 1910, Halley’s next apparition in 1986 was its least favorable in more than 2,000 years of observation. This time, instead of Earth passing through its tail, the comet passed at a distance of 0.42 AU. Barely reaching 2nd magnitude and with a short, fan-shaped tail, Halley was a pale glimmer of its former glory.

But the media hype was incredible. Dozens of countries produced hundreds of stamps, postcards, covers, and other memorabilia commemorating the comet’s passage, as well as the small flotilla of spacecraft en route to collect data from this visitor from the outer solar system. Even today, it is easy to find a broad selection of postage stamps, first day covers, and postcards, most at affordable prices.

Times are a-changin’

The 20th century went out with a bang as two impressive comets — C/1996 B2 (Hyakutake) and C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp) — took turns lighting up the northern skies. Hale-Bopp was magnitude 0 or brighter for many weeks, visible even from the heart of large cities. It was likely the most widely observed comet in history. But by this time, postcards were no longer a medium of choice, so compared to Halley’s Comet, relatively few postcards and covers were produced to commemorate its passage.

Today, online social media platforms have long since overtaken letters and postcards as a primary means of keeping touch. After a major astronomical event such as an eclipse, bright comet, image release from the James Webb Space Telescope, thousands if not millions of images and posts pop up online in a span of a few hours.

But old postcards and covers have a special charm of their own, and true collectors believe they won’t be easily replaced in the hustle of the digital age.