The evening sky boasts several planets as well, but only one, magnificent Saturn, shines brightly. It lingers in twilight during November’s first 10 days. Binocular users can track down Uranus and Neptune throughout the evening hours, while a large telescope can pull in Pluto as it makes a rare close pass by a naked-eye star in Sagittarius.

We’ll begin our tour of the solar system in evening twilight during early November. On the 1st, Saturn stands between 5° and 10° above the southwestern horizon 45 minutes after sunset. (The higher values correspond to observers who live closer to the equator.) Shining at magnitude 0.5, the planet should show up with naked eyes for those with a haze-free sky and an unobstructed horizon. If you can’t spy it right away, binoculars will bring it into view.

Saturn resides among the background stars of northern Scorpius, 8.5° northwest of that constellation’s luminary, 1st-magnitude Antares. You’ll see the ruddy star directly to the planet’s left. The two become increasingly harder to see as the days pass and they dip closer to the horizon. Both disappear during the month’s second week; Saturn passes behind the Sun from our perspective November 29.

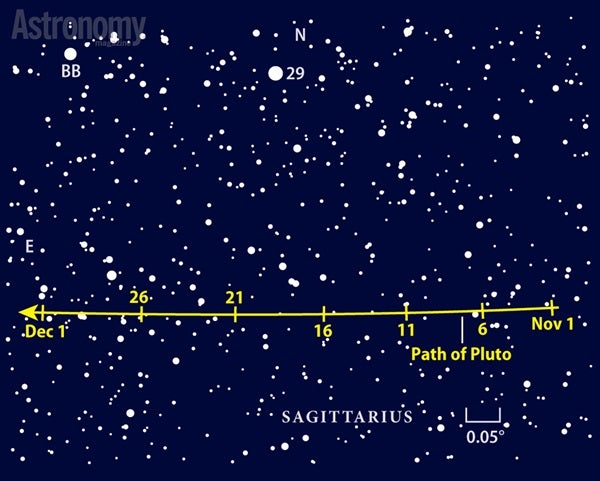

Pluto lurks low in the southwest after darkness falls. Hunt for the magnitude 14.2 world as soon as the last traces of twilight fade away (around 6:15 p.m. local time in mid-November). Pluto then stands nearly 20° high and should be within reach of 10-inch and larger scopes from a dark site. Imagers can capture it through smaller scopes.

A second dwarf planet also lingers in Sagittarius. Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, begins the month in the far eastern part of the constellation. It then crosses northern Microscopium during November’s second and third weeks before entering southern Capricornus. Although you can glimpse the 9th-magnitude asteroid through binoculars, a small telescope makes the task easier. A good time to look is the evening of November 27 when it passes 0.3° north of 4th-magnitude Omega (ω) Capricorni, the constellation’s southernmost bright star.

Neptune hangs much higher in the evening sky. The planet lies against the backdrop of Aquarius the Water-bearer in a region that appears nearly due south and about halfway to the zenith once darkness falls.

Neptune glows at magnitude 7.9, so you’ll need binoculars or a telescope to track it down. Fortunately, it remains in nearly the same spot all month because its slow westward motion against the stellar backdrop comes to an end in mid-November; it then embarks on an equally languid trek to the east. To find it, first locate 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Aquarii through your binoculars, and then scan 6° southwest to pick up 5th-magnitude Sigma (σ) Aqr. Neptune lies 1.5° northeast of Sigma all month. You can confirm a Neptune sighting by targeting the object with a telescope. The planet will show a 2.3″-diameter disk with a pronounced blue-gray color.

Immediately northeast of Aquarius is the constellation Pisces the Fish, the current home of Uranus. The seventh planet reached opposition and peak visibility last month and remains a fine sight throughout November. It resides more than halfway to the zenith in the southern sky nearly all evening.

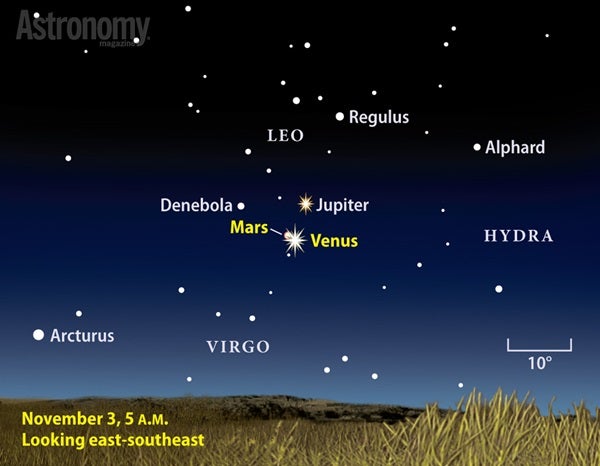

As Uranus dips low in the west in the early morning, a trio of much brighter planets rises in the east. Venus, Mars, and Jupiter all reside in Leo on November 1. While Jupiter remains in this constellation all month, Mars jumps into neighboring Virgo on the 2nd, and Venus follows a day later.

Jupiter is the first of the three to appear. It rises just after 2 a.m. local time on the 1st and climbs 30° high by the time twilight commences around 5 a.m. By the 30th, the giant planet pokes above the horizon two hours earlier and stands 50° high at the first hint of twilight.

Jupiter viewers already have started tracking cloud features in the planet’s massive atmosphere. Beginners immediately notice two dark belts, one on either side of a brighter zone that coincides with the world’s equator. Experienced viewers pick up features within the belts and often spot details at the turbulent boundaries of these cloud bands. The views get better as November progresses and Jupiter grows bigger (its equatorial diameter swells from 33″ to 36″) and climbs higher in the sky. It also grows brighter this month, increasing from magnitude –1.8 to –2.0.

You’ll definitely want to watch Venus and Mars as they dance with each other during November’s first few days. On the 1st, the pair rises a half-hour after Jupiter, and Venus appears 1.1° from Mars. The gap closes to 0.8° by the following morning and then to 0.7° when they appear closest on the 3rd. Venus dazzles at magnitude –4.4, some 275 times brighter than a still respectable magnitude 1.7 Mars.

In the following days, watch as the waning crescent Moon passes by the planet trio. On the 6th, the 23-percent-lit Moon stands a few degrees to Jupiter’s right; on the 7th, Luna (now 16 percent illuminated) appears within 2° of both Venus and Mars. Grab your camera to capture the scenes on these two mornings. From mid-northern latitudes, all these objects rise before 3 a.m. local time. And shortly after 5 a.m., the eastern sky starts to brighten with the approach of dawn, adding gorgeous twilight colors to your images.

Venus and Mars continue to stretch out across Virgo during November. Venus moves faster relative to the background stars, passing 1° south of 3rd-magnitude Gamma Virginis on the 18th and 4° north of 1st-magnitude Spica on the 28th. (Through a telescope in November’s final days, the planet appears 18″ across and two-thirds lit.) Mars’ slower eastward motion has it sliding 1° south of Gamma Vir on November 30.

Keen-eyed observers might be able to glimpse Mercury on November’s first morning. The innermost planet then shines brightly at magnitude –1.0 but lies just 4° high in the east-southeast 30 minutes before sunrise. Mercury passes behind the Sun from our perspective on the 17th and will return to view on December evenings.

Many people avoid observing around the time of Full Moon because its light washes out fainter objects and renders brighter ones more difficult to see. But skywatchers will be glued to the Full Moon the night of November 25/26 as it passes 1st-magnitude Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus the Bull.

Observers in Canada and the northern United States will see our satellite occult (pass in front of) the star in the predawn hours of November 26, while those in the southern tier of states will witness the Moon passing just north of Aldebaran. Viewers located along a narrow track that stretches from the California-Oregon border to South Carolina will experience a grazing occultation. Seen through a telescope, the star will disappear behind lunar mountains and then reappear through valleys, often many times within a few minutes. The event occurs at roughly 6 a.m. EST (3 a.m. PST), though the timing varies depending on your location. Check out Brad Timerson’s predictions at www.iota.timerson.net for precise times for your site.

The lunar crater Plato impresses the newcomer as much as it mesmerizes experienced selenophiles. During the early evening of November 19, the large half-lit oval is a striking sight in the Moon’s northern half. The Sun paints long jagged shadows onto the canvas of its smooth floor. Over the course of the next few hours, the Sun climbs higher in the lunar sky and forces their retreat.

The mountains along the crater’s rim are not as sawtooth-shaped as their shadows imply. You can test this by stepping outside near sunset and confirming that your own head isn’t as pointy as its shadow!

The central peaks that formed during Plato’s birth lie hidden below the now-solid surface. During the great floods some 3.5 billion years ago, red-hot molten lava welled up through cracks in the crater’s floor but could get no farther than the high walls. Since then, a handful of modestly small impacts have pitted the frozen floor. Through a 6-inch telescope and a steady atmosphere, patient observers can pick out the largest of these craterlets near Plato’s center.

It pays to return to Plato on the next couple of evenings. The higher Sun better shows off the way the crater’s walls have slumped into the basin. You can replicate some of these features the next time you’re at the beach. Simply dig a few holes to different depths in the moist sand, and watch how the sides cave in. It’s also fun to compare the texture just inside and outside Plato’s rim — the smooth floor appears noticeably different from the dappled area beyond the crater’s wall.

After you’ve examined Plato on the 19th, shift your scope’s aim to just south of the lunar equator. There you will see the stunning Straight Wall casting a thin black shadow.

The night of November 17/18 brings the peak of the annual Leonid meteor shower. The waxing crescent Moon sets around 10 p.m. local time, leaving the favored morning hours free from its glare. The meteors appear to radiate from the Sickle asterism in Leo the Lion, a region that climbs high in the southeast before dawn. Experts predict that observers under clear, dark skies will see up to 15 meteors per hour.

Leonids strike Earth’s atmosphere at 44 miles per second, the fastest of any meteors. The high speeds mean they produce more fireballs — brilliant meteors that shine at least as brightly as Venus — than most showers.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Saturn (southwest) |

Uranus (southwest) |

Mercury (east) |

| Uranus (east) |

Neptune (west) |

Venus (southeast) |

| Neptune (southeast) |

Mars (southeast) |

|

| |

Jupiter (southeast) |

|

| |

||

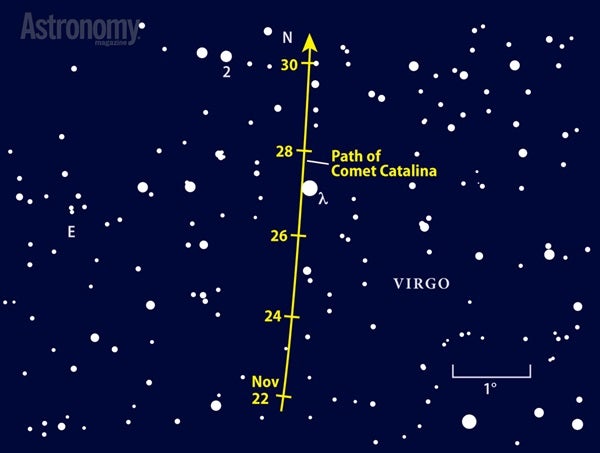

Late November should bring a nice binocular comet into view for Northern Hemisphere observers. Astronomers predict Comet Catalina (C/2013 US10) could reach 4th magnitude by the end of the month, bringing welcome relief after a summer of faint dirty snowballs. Still, if you want to see its 2°-long tail, you’ll have to plan a predawn observing session at a country location with a dark eastern horizon.

The comet reaches perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun, in mid-November, so its gas and dust production should be near maximum. The timing couldn’t be better because Catalina moves northward and thus climbs higher in the eastern sky with each passing day. That trend will continue into early next year, by which time

it will be visible all night.

Your first opportunity to view the comet comes around November 22 when it just clears the horizon by the start of twilight. Catalina then lies in southeastern Virgo, near that constellation’s border with Libra. Use magnitude 4.5 Lambda (λ) Virginis as your guide. The comet passes just 0.1° east of this star the morning of the 27th. Although the Moon returned to the morning sky a couple of days earlier (on the 25th), you should still give the comet a try.

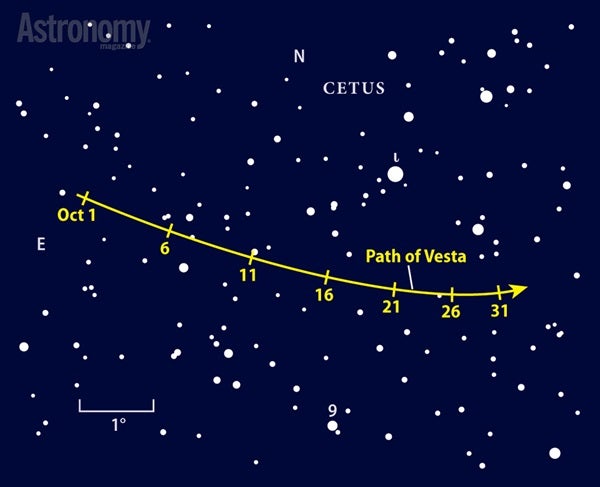

Asteroid 4 Vesta ranks as one of the easiest asteroids to find and track largely because it is so bright. Even though it reached opposition and peak visibility in late September, it still shines at 7th magnitude this month and remains well placed for Northern Hemisphere observers using binoculars or a telescope.

You can find Vesta about halfway up in the southern sky during midevening. It spends the month within a couple of degrees of the magnitude 3.5 star Iota (ι) Ceti, which itself lies 11° north-northwest (to the upper right) of 2nd-magnitude Beta (β) Ceti.

You might consider a simple one- to two-month sketching or imaging project that tracks this 325-mile-wide asteroid. In mid-November, Vesta’s westward motion relative to the background stars comes to a stop, and the space rock then begins moving to the east. With only a piece of paper and a few dots to mark the location of nearby stars, return every two or three nights to place a new point on the sheet. Only five stars within a 2° field shine brighter than Vesta. Imagers can align and stack their exposures, revealing the non-stellar intruder as a curving line of little pearls.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.