By directly detecting gravitational waves, LIGO has given us a whole new way of observing the universe. That extraordinary technical accomplishment and the discoveries it promises are awe-inspiring. We had been blind, but now we can see!

Of course, astrophysicists had already known that gravitational waves exist for four decades before the LIGO announcement. LIGO scientists recount that history in the opening paragraphs of their own 2016 paper in Physical Review Letters: “The discovery of the binary pulsar system PSR B1913+16 by Hulse and Taylor and subsequent observations of its energy loss by Taylor and Weisberg demonstrated the existence of gravitational waves.”

In 1974, the binary pulsar was the test of Einstein’s theory that everyone had been waiting for. Had the orbit of the binary pulsar not decayed as predicted, the headlines would have read, “Einstein wrong! Gravitational waves don’t exist!” And LIGO would never have been built. Hulse and Taylor were awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work. Isaac Newton famously said, “If I have seen further than others it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” For LIGO, those giants included Hulse, Taylor, and Weisberg.

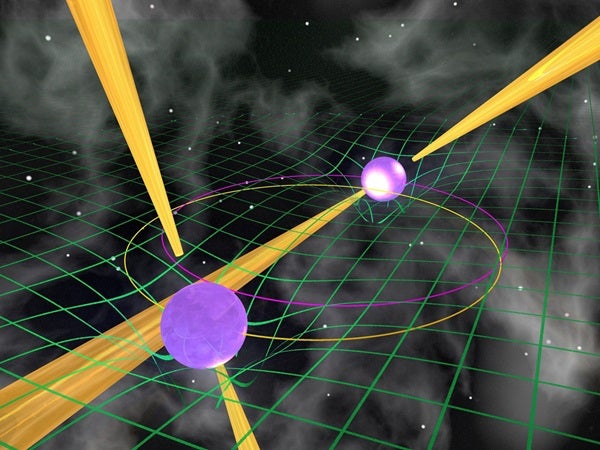

During the gravitational waves press conference, Rainer Weiss, a LIGO co-founder, seemed about to tell that story. He set it up beautifully, talking about the rapid orbital decays of collapsed objects like black holes and neutron stars. The next words out of his mouth should have been “Hulse and Taylor.” Instead it was as if a chapter had been eliminated from a book. In the narrative, suddenly it was 2015 and LIGO was confirming Einstein’s predictions for the first time.

Another surprising omission came later. When Kip Thorne, black hole expert and fellow LIGO co-founder, took his turn at the mic, he enthused, “All of our previous windows through which astronomers have looked are electromagnetic!” In the process he ignored not one but two Nobel Prizes. The 2002 and 2015 prizes both recognized neutrino astronomy, which not only confirmed our fundamental understanding of the workings of stars and core-collapse supernova explosions, but also provided the first hard evidence of a failure of the Standard Model of particle physics — neutrinos were supposed to be massless.

Maybe I’m just being a curmudgeon. Events like the LIGO press conference are about sharing the excitement of a moment. Believe me, I get it. I was among those who addressed the American Astronomical Society in January 1994, celebrating the successful repair of the Hubble Space Telescope. Sometimes you have to shout “we’re number one!” and spike the ball in the end zone.

Then there is realpolitik. Back in the day, then Hubble project scientist Ed Weiler had a favorite saying: “Congress doesn’t read The Astrophysical Journal. Congress reads The New York Times.” He was right.

As the most expensive project ever supported by the National Science Foundation, LIGO faces that same reality. Press conferences are important. They are scripted and rehearsed, with PR types directing the show. That’s fine. But when crucial things like the binary pulsar and neutrino astronomy aren’t mentioned, it is usually because someone worried they would “detract from the story.” That’s not OK.

Maybe an example best illustrates my concerns. When then presidential candidate Rick Perry ridiculed climate science, he would typically sidestep the science itself and instead attack the credibility of scientists. “There are a substantial number of scientists who have manipulated data so that they will have dollars rolling into their projects,” he claimed in a speech to New Hampshire voters in 2011.

Those attacks were unfounded, but a lot of people were (and are) predisposed to believe them anyway. Perry was tapping into and reinforcing a common perception that scientists routinely gild the lily in their all-consuming quest for publicity and funding. He marginalized solid and important research by painting scientists as hucksters.

Over the years I’ve heard that sentiment more times than I can count. “Hey Jeff, what’s this new thing? What’s the spin? How much of it is real?” Is the LIGO press conference to blame for that perception? Of course not! But, if only in small ways, LIGO did play that game.

The detection of gravitational waves from merging black holes was a truly profound and triumphant event. A few spoken sentences placing LIGO in its proper historical and scientific context would only have added to the celebration of such an extraordinary accomplishment.

Jeff Hester is a keynote speaker, coach, and astrophysicist. Follow his thoughts at jeff-hester.com