Having something block your view when taking a photo can be a real pain — except perhaps when studying cosmic mirages and dark matter.

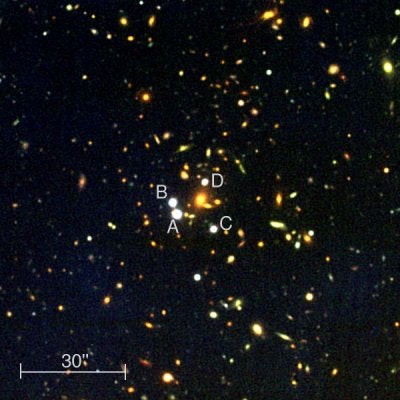

Astronomers have discovered a gravitationally lensed quasar located more than 10 billion light-years away that is shedding new light on dark matter in the universe. Parked behind a massive cluster of galaxies, the quasar’s feeble light has been bent and split into four distorted images that have the largest angular separation ever found. According to the discovery team, this wide-angle effect is evidence that invisible cold dark matter dominates the foreground cluster and is responsible for the record-breaking quadruple mirage.

Since 1979, more than 80 gravitationally lensed quasars have been cataloged, however none were found to have separations of more than 7 arcseconds. Despite theoretical models that predicted larger splitting of quasar images, numerous searches had come up empty — until now.

Mining the colossal database of over 30,000 quasars from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), an international team of astronomers led by Naoisha Inada and Masamune Oguri from the University of Tokyo pinpointed SDSS J1004+4112 in the constellation Leo Minor.

“Additional observations obtained at the Subaru 8.2-meter Telescope and Keck Telescope confirmed that this system is indeed a gravitational lens,” explains lead author Inada. “Quasars split this much by gravitational lensing are predicted to be very rare, and thus can only be discovered in very large surveys like the SDSS.”

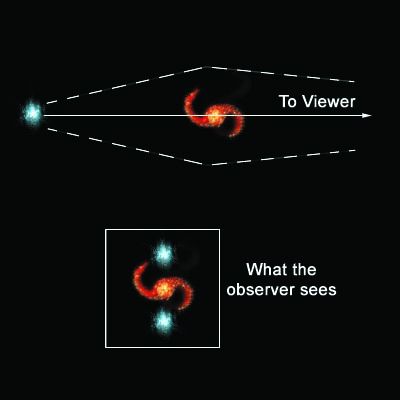

First predicted by Einstein more than six decades ago, gravitational lensing occurs when the gravity from a massive foreground object bends and amplifies the light from a more distant object, as seen from Earth. Astronomers have been using this giant magnifying-lens effect to bring into view quasars and galaxies that otherwise would be too faint to detect. Some lensed quasars produce multiple images including, in rare cases (if the alignment is perfect), rings around the lensing galaxies.

Oguri added: “Discovering one such wide gravitational lens out of over 30,000 SDSS quasars surveyed to date is perfectly consistent with theoretical expectations of models in which the universe is dominated by cold dark matter. This offers additional strong evidence for such models.”

The authors expect many more such wide-angle lensed quasars will be encountered and that they will become powerful tools in the study of the distribution of dark matter in the universe. “The gravitational lens we have discovered will provide an ideal laboratory to explore the relation between visible objects and invisible dark matter in the universe,” adds Oguri.