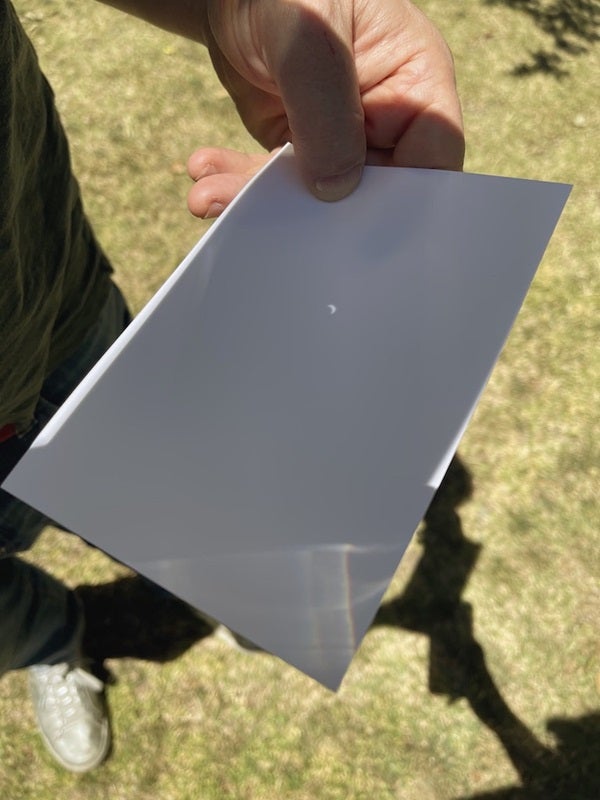

Solar eclipses give astronomers a unique opportunity to view objects around the Sun, such as Mercury and nearby stars normally blocked by the Sun’s brilliance.

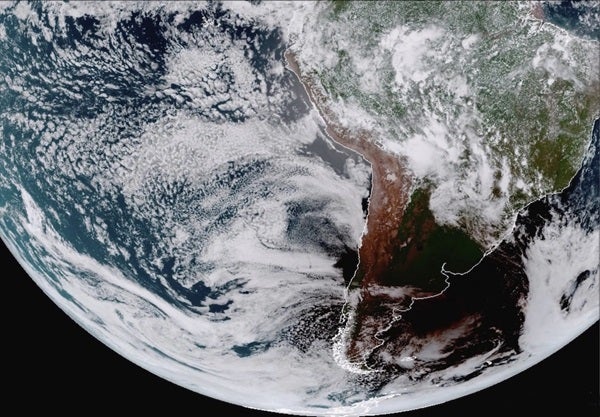

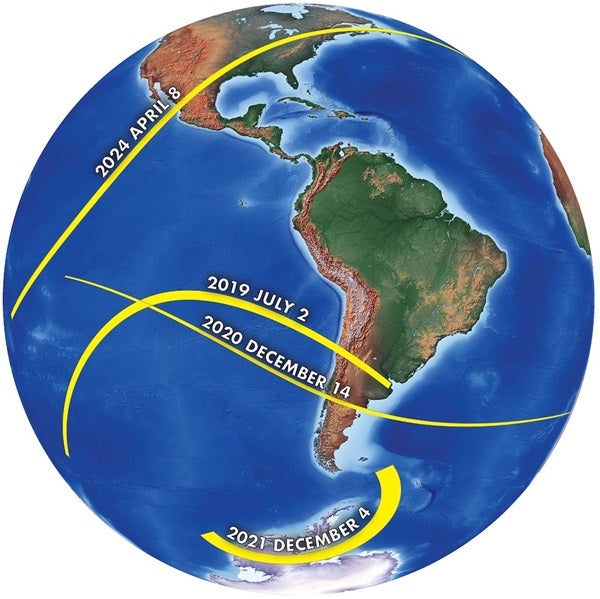

Unlike totality during the July 2, 2019, eclipse — which was visible low in the sky along a narrow path through Chile and Argentina shortly before sunset — the December 14, 2020, total eclipse was high in the sky over the Patagonia region in South America. But that wasn’t the only major difference between the two eclipses. Planning for the December 2020 total solar eclipse was especially sporadic due to fluctuating travel restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. My scientific team’s original plans involved accompanying a tour group to a viewing site in Argentina, but restrictions led to the cancellation of most tours, including our own. However, my team still managed to obtain permission to enter Chile and view from the otherwise-closed Villarrica National Park.

Capturing an eclipse

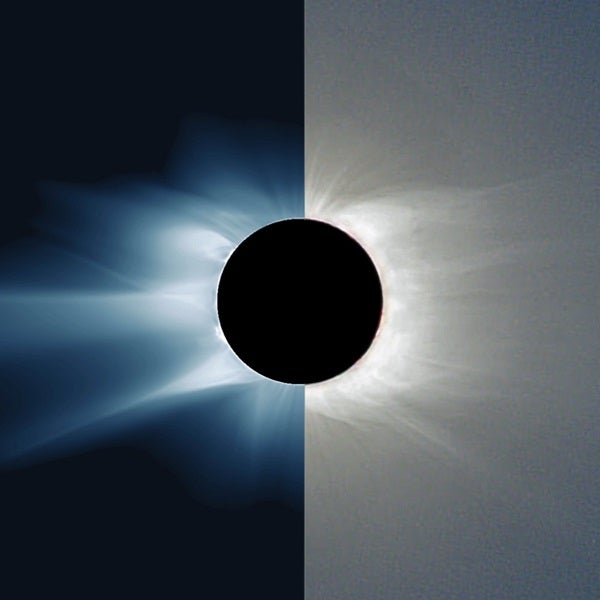

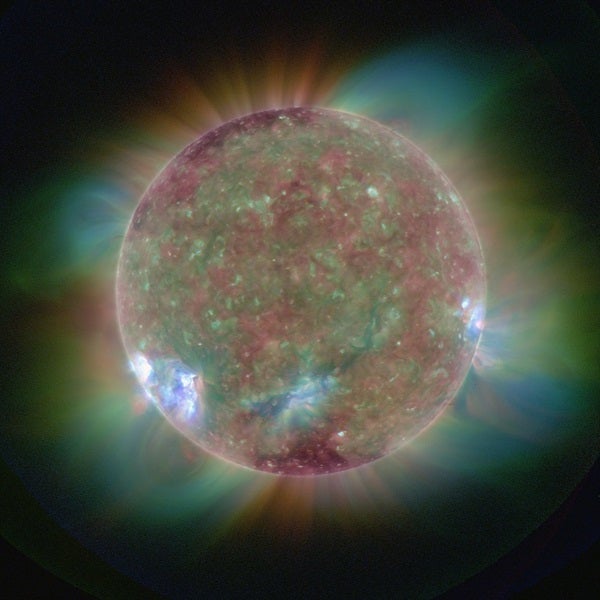

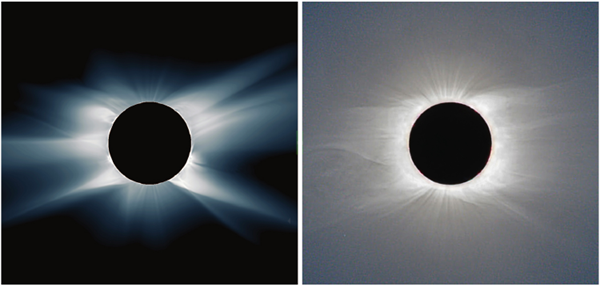

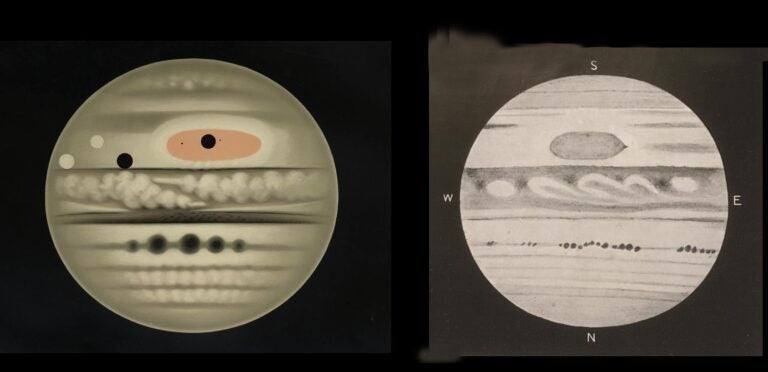

Leading up to the eclipse, a research group from Predictive Science Inc. continued their streak of predicting what the Sun’s corona would look like. These computations were based on observations from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory of the solar magnetic field in the months leading up to the eclipse. Because the Sun’s activity cycles from low to high and back to low about every 11 years, and the latest cycle began at the end of 2019, the researchers predicted that observers would see increased activity, such as forked streamers near the equator on either side of the Sun as well as plumes emanating from the poles. After the eclipse, some of the earliest images we received showed such prominences arcing up from the surface of the Sun.

The first notification I received of coronal observations through reasonably clear skies came from Andreas Möller of Germany, who had gone to Argentina with the U.K. Astro-Trails tour — one of the few tours that had not been canceled — to a site at Piedra del Águila. Back in New York City, my longtime colleague, computer-adept composer Wendy Carlos, created a composite of Möller’s images by choosing the best exposed part of each. She sent the result to Joy Ng and Lina Tran of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who compared the photos with predictions generated by Predictive Science Inc. The resulting press release not only shows a fade from their prediction to our actual image of the event, but also provides a slider that allows readers to compare the two images in detail.

Comet light, comet bright

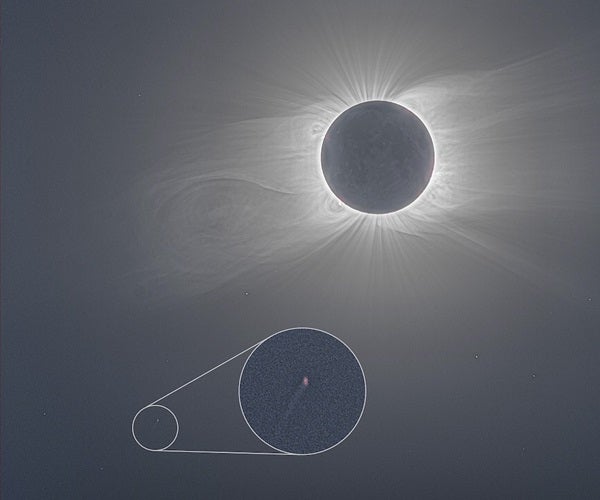

Looking through satellite data from the NASA-funded citizen science Sungrazer Project, Thai amateur astronomer Worachate Boonplod spotted a new comet speeding by the Sun on December 13, a day before the eclipse. Sungrazer encourages citizens scientists to scour images from the joint European Space Agency and NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) to find new comets. Astronomers were eager to see if the little speck would be visible in eclipse photographs.

Hopeful it would appear in ground-based observations, I sent a full set of Andreas Möller’s raw eclipse images to my colleagues Vojtech Rusin and Roman Vanur in Slovakia. Lo and behold, Vanur’s resulting composite, made from five dozen of Möller’s images, indeed shows the comet.

Considering about 2,000 SOHO comets are still unnumbered, I reached out to the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, encouraging them to number this new comet. It soon became SOHO–4108. Later, the International Astronomical Union Minor Planet Center at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory released the comet’s new name — C/2020 X3 (SOHO). Additional observations showed it to be a Kreutz sungrazer, a family of comets stemming from a parent comet that broke up well over a thousand years ago.

Looking forward

What’s next? We have plenty of observations to keep us busy, but that doesn’t mean we aren’t already planning to collect more in the future, as the Sun continues through its sunspot cycle. This year’s annular eclipse over Canada, northwestern Greenland, the North Pole, and Siberia on June 10, 2021, will have partial phases visible in the northeastern U.S. Unfortunately the same can’t be said for the Antarctica eclipse on December 4, 2021. Predictions made by Jay Anderson at http://eclipsophile.com indicate clouds will impact the viewing.

But those annular eclipses are child’s play compared to what’s coming in 2024: The next Great American Eclipse. Totality during this much-anticipated event will cross from Mexico through Texas and on through the upper Midwest to northern New England and the Canadian Maritimes. And, if one can bear to wait a few more decades, the May 1, 2079, total solar eclipse will cross over both New York and Boston.

Regardless of which eclipse you may see, you certainly won’t be disappointed — whether you’re an astronomer or simply an eclipse enthusiast.