These findings, as well as information gleaned from a recent NASA EPOXI spacecraft flyby of Comet 103P/Hartley, are expected to offer new insights as researchers strive to better understand comets and the role they could possibly play in aiding human solar system exploration, said Nalin H. Samarasinha from PSI.

“Understanding the makeup of comets has immediate relevance to planetary exploration efforts. Small bodies of the solar system such as asteroids and comets could potentially act as way stations, as well as to supply needed resources, for the human exploration of the solar system,” Samarasinha said. “For this purpose, it is necessary to know the properties and the character of these objects to maximize our investment.”

The research team analyzed images of the rotationally excited, or tumbling, Hartley comet taken during 20 nights between September 1 and December 15, 2010, using the 2.1-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona.

A blue filter that isolates the light emitted by cyanogen (CN) molecules was used to observe CN features in the coma of the comet, Samarasinha said. This showed clear variations during timescales ranging from a few hours to several days. The coma is the extended “atmosphere” of the comet that surrounds the solid nucleus that consists of ice and dirt.

“The rotational state of a comet’s nucleus is a basic physical parameter needed to accurately interpret other observations of the nucleus and coma,” Samarasinha said. “Analysis of these cyanogen features indicates that the nucleus is spinning down and suggests that it is in a state of a dynamically excited rotation.Our observations have clearly shown that the effective rotation period has increased during the observation window.”

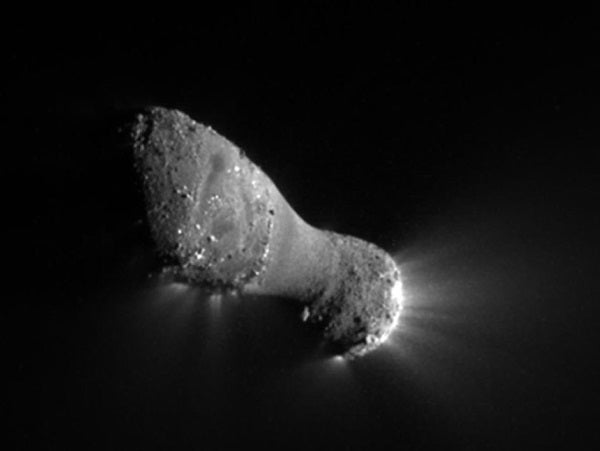

Hartley, a relatively small comet with a 1.2-mile-long (2 kilometers) nucleus, is highly active for its size, he said. It is experiencing rotational changes due to torque caused by jets of gases emitting from the icy body.

Information on the makeup of Comet Hartley gleaned from this research and the EPOXI flyby, and similar research on additional comets, could offer the early tools researchers need to determine the best way to deal with a comet on a collision course with Earth.

“Although extremely rare, comets can collide with Earth. This could cause regional or global damage to the environment and to life on Earth,” Samarasinha said. “However, fortunately for the first time, we are on the threshold of our technical know-how to mitigate such a hazardous impact. In order to do that, we need to know the material properties of comets. The most appropriate mitigation strategy for a strong rigid body is different from that for a weakly bound agglomerate.”

Hartley offered a significant opportunity for research, said Beatrice E.A. Mueller from PSI.

“This comet had such a great apparition. It came close to Earth and was observable from the ground over months with great resolution, and was encountered by the EPOXI spacecraft,” said Mueller. “Ultimately, one wants to deduce the physical parameters of the nucleus as well as its structure. This will give insights into the conditions during the formation of the solar system.”

These findings, as well as information gleaned from a recent NASA EPOXI spacecraft flyby of Comet 103P/Hartley, are expected to offer new insights as researchers strive to better understand comets and the role they could possibly play in aiding human solar system exploration, said Nalin H. Samarasinha from PSI.

“Understanding the makeup of comets has immediate relevance to planetary exploration efforts. Small bodies of the solar system such as asteroids and comets could potentially act as way stations, as well as to supply needed resources, for the human exploration of the solar system,” Samarasinha said. “For this purpose, it is necessary to know the properties and the character of these objects to maximize our investment.”

The research team analyzed images of the rotationally excited, or tumbling, Hartley comet taken during 20 nights between September 1 and December 15, 2010, using the 2.1-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona.

A blue filter that isolates the light emitted by cyanogen (CN) molecules was used to observe CN features in the coma of the comet, Samarasinha said. This showed clear variations during timescales ranging from a few hours to several days. The coma is the extended “atmosphere” of the comet that surrounds the solid nucleus that consists of ice and dirt.

“The rotational state of a comet’s nucleus is a basic physical parameter needed to accurately interpret other observations of the nucleus and coma,” Samarasinha said. “Analysis of these cyanogen features indicates that the nucleus is spinning down and suggests that it is in a state of a dynamically excited rotation.Our observations have clearly shown that the effective rotation period has increased during the observation window.”

Hartley, a relatively small comet with a 1.2-mile-long (2 kilometers) nucleus, is highly active for its size, he said. It is experiencing rotational changes due to torque caused by jets of gases emitting from the icy body.

Information on the makeup of Comet Hartley gleaned from this research and the EPOXI flyby, and similar research on additional comets, could offer the early tools researchers need to determine the best way to deal with a comet on a collision course with Earth.

“Although extremely rare, comets can collide with Earth. This could cause regional or global damage to the environment and to life on Earth,” Samarasinha said. “However, fortunately for the first time, we are on the threshold of our technical know-how to mitigate such a hazardous impact. In order to do that, we need to know the material properties of comets. The most appropriate mitigation strategy for a strong rigid body is different from that for a weakly bound agglomerate.”

Hartley offered a significant opportunity for research, said Beatrice E.A. Mueller from PSI.

“This comet had such a great apparition. It came close to Earth and was observable from the ground over months with great resolution, and was encountered by the EPOXI spacecraft,” said Mueller. “Ultimately, one wants to deduce the physical parameters of the nucleus as well as its structure. This will give insights into the conditions during the formation of the solar system.”