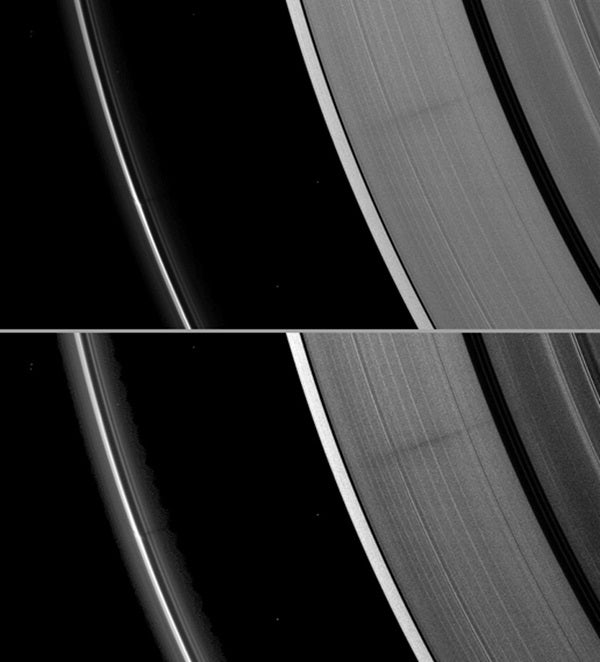

The structure can be seen as a bulge within the bright core of the F ring on the left of the image. The structure rises far enough above the ring plane for the shadow to be cast across the Roche Division and onto the A ring. The shadow is barely visible stretching across the top right quadrant of the image. The shadow appears very faint here because this view looks toward the unlit side of the rings.

Thanks to a special play of sunlight and shadow as Saturn continues its march towards its August 11 equinox, recent images captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft are revealing new three-dimensional objects and structures in the planet’s otherwise flat rings.

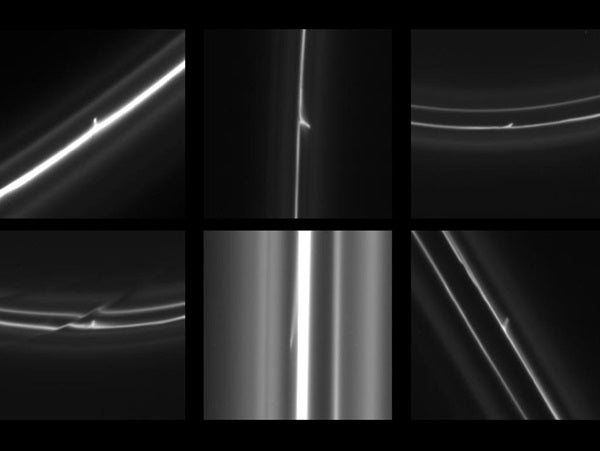

Through the detections of shadows cast upon the rings, a moonlet has been spotted for the first time in Saturn’s dense B ring and narrow vertical structures are seen soaring upward from Saturn’s intricate F ring.

The search for three-dimensional structures in Saturn’s rings has been a major goal of the imaging team during Cassini’s “Equinox Mission,” the 27-month-long period containing exact equinox — that moment when the Sun is seen directly overhead at noon at the planet’s equator. This novel illumination geometry occurs every half-Saturn-year, or about 15 Earth years. It lowers the Sun’s angle to the ring plane and causes out-of-plane structures to cast long shadows across the rings’ broad expanse, making them easy to detect.

Saturn’s rings are hundreds of thousands of miles wide, but the main rings — D, C, B and A rings (working outward from the planet) — are only about 30 feet (10 meters) thick. These main rings lie inside the relatively narrow F ring. The thinness of the rings — well below the resolving power of the spacecraft’s cameras — makes the determination of vertical deviations from them difficult through routine imaging. Solid evidence of these newly seen structures and others like them become available only during the period of equinox when features protruding above and below the rings can cast shadows.

The structure can be seen as a bulge near the bright core of the ring on the right of the image. Imaging scientists are working to understand the origin of structures such as this one, but they think this image shows the shadow of what appears to be a vertically extended object in the core of the F ring.

The second (bottom) version of the image has been brightened to enhance the visibility of the ring and shadow. Background stars appear elongated in the image because of the camera’s exposure time.

In recent weeks, scientists also have collected a series of images of shadows being cast by vertically extended structures or objects in the F ring. One image shows the shadow of what appears to be a vertically extended object in the core of the F ring, while another image may show the shadow of an object on an inclined orbit that has punched through the F ring and dragged material along in its path. A third image shows an F-ring structure casting a shadow long enough to reach across the wide Roche Division and appear on the A ring. Imaging scientists are working to understand the origin of these structures.

New sights such as these — and the questions they raise and the insights they may provide — will continue in the coming days of Saturn’s equinox.