Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and Rosetta now lie 252 million miles (405 million kilometers) from Earth, about halfway between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars, rushing toward the inner solar system at nearly 34,000 mph (55,000 km/h).

Related: See all the latest images from Rosetta

The comet is in an elliptical 6.5-year orbit that takes it from beyond Jupiter at its furthest point to between the orbits of Mars and Earth at its closest to the Sun. Rosetta will accompany it for over a year as they swing around the Sun and back out toward Jupiter again.

Comets are considered to be primitive building blocks of the solar system and may have helped “seed” Earth with water, perhaps even the ingredients for life. But many fundamental questions about these enigmatic objects remain, and through a comprehensive,in-situ study of the comet, Rosetta aims to unlock the secrets within.

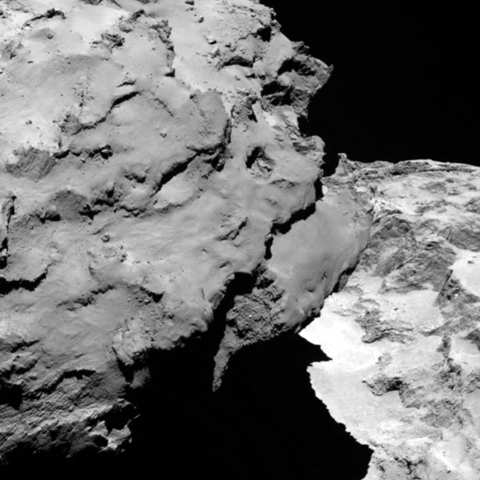

Close-up detail of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The image was taken by Rosetta’s OSIRIS narrow-angle camera and downloaded August 6. The image shows the comet’s “head” at the left of the frame, which is casting shadow onto the “neck” and “body” to the right. The image was taken from a distance of 75 miles (120 kilometers) and the image resolution is 7.2 feet (2.2 meters) per pixel.

“After 10 years, five months, and four days traveling towards our destination, looping around the Sun five times and clocking up 6.4 billion kilometers [4.0 billion miles], we are delighted to announce finally ‘we are here,’” said Jean-Jacques Dordain, ESA’s director general. “Europe’s Rosetta is now the first spacecraft in history to rendezvous with a comet, a major highlight in exploring our origins. Discoveries can start.”

Today saw the last of a series of 10 rendezvous maneuvers that began in May to adjust Rosetta’s speed and trajectory gradually to match those of the comet. If any of these maneuvers had failed, the mission would have been lost, and the spacecraft would simply have flown by the comet.

“Today’s achievement is a result of a huge international endeavor spanning several decades,” said Alvaro Giménez, ESA’s director of science and robotic exploration. “We have come an extraordinarily long way since the mission concept was first discussed in the late 1970s and approved in 1993, and now we are ready to open a treasure chest of scientific discovery that is destined to rewrite the textbooks on comets for even more decades to come.”

The comet began to reveal its personality while Rosetta was on its approach. Images taken by the OSIRIS camera between late April and early June showed that its activity was variable. The comet’s “coma” — an extended envelope of gas and dust — became rapidly brighter and then died down again over the course of those six weeks.

In the same period, first measurements from the Microwave Instrument for the Rosetta Orbiter, MIRO, suggested that the comet was emitting water vapor into space at about 300 milliliters per second.

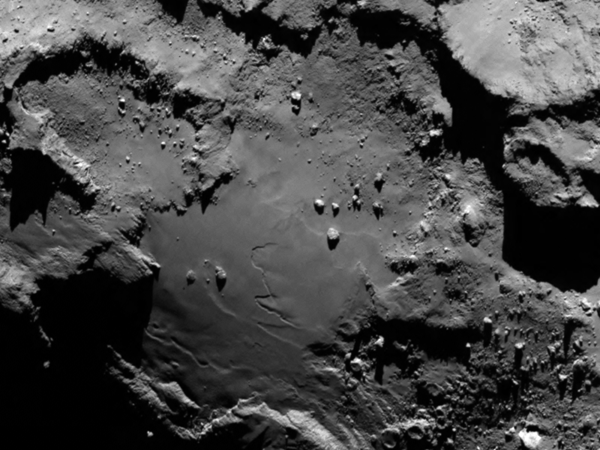

Meanwhile, the Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer, VIRTIS, measured the comet’s average temperature to be about –94° Fahrenheit (–70° Celsius), indicating that the surface is predominantly dark and dusty rather than clean and icy.

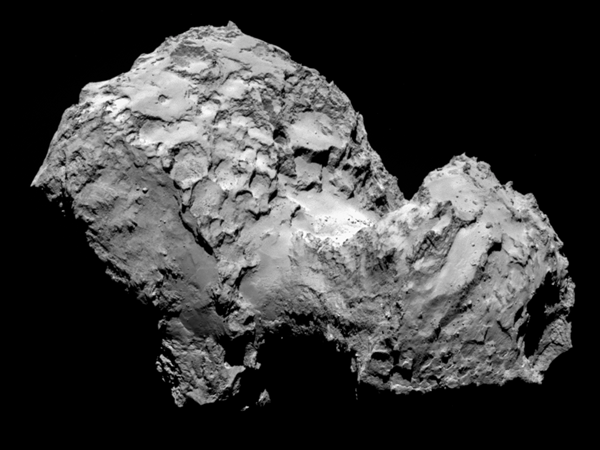

Then, stunning images taken from a distance of about 7,500 miles (12,000km) began to reveal that the nucleus comprises two distinct segments joined by a “neck,” giving it a duck-like appearance. Subsequent images showed more and more detail.

“Our first clear views of the comet have given us plenty to think about,” said Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist. “Is this double-lobed structure built from two separate comets that came together in the solar system’s history, or is it one comet that has eroded dramatically and asymmetrically over time? Rosetta, by design, is in the best place to study one of these unique objects.”

The image was taken from a distance of 80 miles (130 kilometers) and the image resolution is 7.9 feet (2.4 meters) per pixel.

At the same time, more of the suite of instruments will provide a detailed scientific study of the comet, scrutinizing the surface for a target site for the Philae lander.

Eventually, Rosetta will attempt a close, near-circular orbit at 20 miles (30km) and, depending on the activity of the comet, perhaps come even closer.

“Arriving at the comet is really only just the beginning of an even bigger adventure, with greater challenges still to come as we learn how to operate in this unchartered environment, start to orbit and, eventually, land,” said Sylvain Lodiot, ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft operations manager.

As many as five possible landing sites will be identified by late August before the primary site is identified in mid-September. The final timeline for the sequence of events for deploying Philae — currently expected for November 11 — will be confirmed by the middle of October.

“Over the next few months, in addition to characterizing the comet nucleus and setting the bar for the rest of the mission, we will begin final preparations for another space history first: landing on a comet,” said Taylor. “After landing, Rosetta will continue to accompany the comet until its closest approach to the Sun in August 2015 and beyond, watching its behavior from close quarters to give us a unique insight and real-time experience of how a comet works as it hurtles around the Sun.”