If you look to the southwest about a half-hour after sunset, Jupiter should pop into view. On June 1, the planet stands halfway to the zenith as darkness falls. It shines at magnitude –2.1 and appears far brighter than the background stars of Leo the Lion. Jupiter sets around 2 a.m. local daylight time in early June and some two hours earlier by month’s end, when the best views come shortly after twilight ends.

The gas giant’s atmosphere shows wonderful detail even through small telescopes. The most obvious features are two dark belts that straddle a brighter zone coinciding with the planet’s equator. More subtle features appear with patient viewing and good seeing conditions. All this activity takes place on a disk that spans 36″ in mid-June.

Equally impressive are the four bright Galilean moons. Callisto, the outermost of these satellites, crosses in front of Jupiter’s north polar region twice this month. North American observers get a good view of the June 8 transit, which begins at 11:02 p.m. EDT. About 90 minutes later, Callisto appears halfway across the planet’s disk. From the East Coast, Jupiter sets by the time the transit concludes at 2:15 a.m. on the 9th, but it is still visible out west.

Whenever a satellite’s orbital motion carries it to Jupiter’s far side, the planet’s girth hides it from view. A rare treat awaits observers the night of June 13/14 when two moons disappear within minutes of each other. Early in the evening, you’ll see Io and Ganymede near Jupiter’s western limb. Ganymede, the solar system’s largest moon, disappears at 12:35 a.m. EDT; Io follows 10 minutes later.

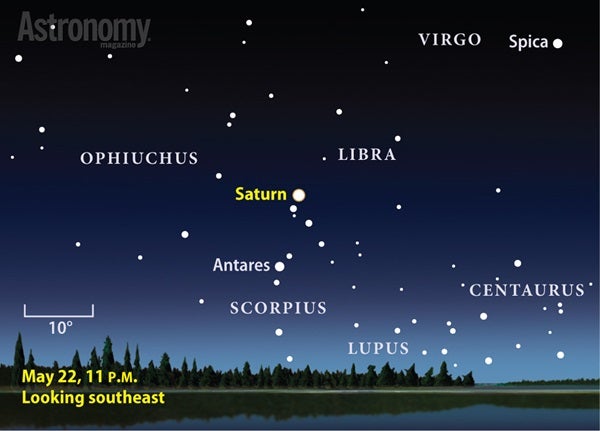

While the western sky claims Jupiter on these warm summer evenings, the eastern sky boasts two bright planets. Mars shines at magnitude –2.0 and Saturn at magnitude 0.0 as June begins, when the Red Planet lies 15° west of its ringed cousin. Adding to the scene is 1st-magnitude Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius the Scorpion. The stunning trio dominates the southeastern sky at nightfall and appears due south around midnight local daylight time. A nearly Full Moon passes through this vicinity from June 16–18.

The planet’s dimming reflects its motion away from Earth, so it should come as no surprise that the world appears to shrink. When viewed through a telescope June 1, Mars spans 18.6″, the same as it was at closest approach May 30. By the end of June, the planet’s diameter has dwindled to 16.5″. Still, that’s plenty big enough to show major features through small instruments, particularly when Mars climbs highest around midnight.

The one feature visible throughout the month is the north polar cap, which appears as a white region on the planet’s northern limb. Mars’ axis tilts about 15° toward Earth in June, keeping the north pole on constant display. After the ice cap, the two most conspicuous features are the dark region Syrtis Major and the bright Hellas basin. Conveniently, Hellas lies due south of Syrtis Major. From North America, both appear near Mars’ central meridian around midnight local daylight time during June’s final week.

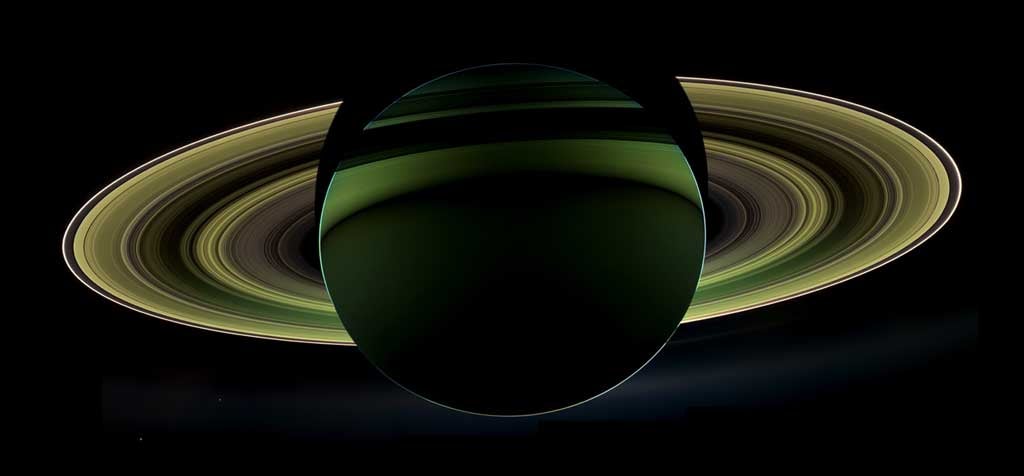

Next up is Saturn, which reaches opposition the night of June 2/3 among the background stars of southern Ophiuchus. The ringed planet then lies low in the southeast after sunset and remains visible all night. It peaks some 30° above the southern horizon around 1 a.m. local daylight time. Like Mars, Saturn moves westward relative to the starry backdrop this month, but at a slower pace because it lies much farther from the Sun and thus orbits more sluggishly.

At opposition, Saturn appears biggest through a telescope. The rings dominate the view because they reflect significantly more light than the planet’s cloud tops. At the peak, the ring system spans 42″, more than double the 18″ diameter of Saturn’s disk. Even a small scope delivers exquisite views, enhanced by the 26° tilt of the rings. The most obvious ring feature is the dark Cassini Division that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring.

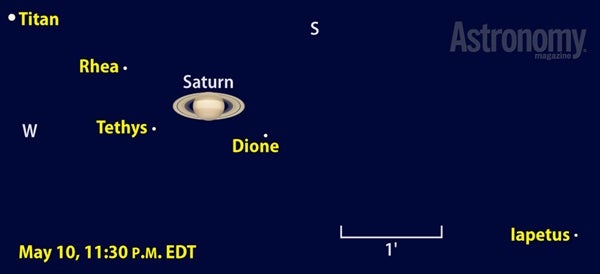

Closer in lies a trio of 10th-magnitude moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — that all take less than five days to complete an orbit. A 4-inch scope is plenty to reveal these three. Sometimes they form nice configurations, as they do June 22 when they line up northwest of Saturn.

A bit fainter is distant Iapetus. It glows at 11th magnitude when it passes 2.1′ south of Saturn the night of June 1/2. It brightens nearly a full magnitude by the time it reaches greatest western elongation June 21/22, when its brighter hemisphere faces Earth. It then lies 9′ from Saturn, however, and is a bit tougher to pick

out. Don’t confuse it with the 6th-magnitude field star SAO 184541, which then appears between the moon and Saturn. (On the following two nights, this star comes even closer to the planet and looks like an abnormally bright moon.)

Much closer to Saturn, and devilishly faint at 12th magnitude, is the icy moon Enceladus. The rings’ brilliance typically drowns out this water-spewing satellite. The best time to look for it is when it lies near greatest elongation, as it conveniently does the night of opposition.

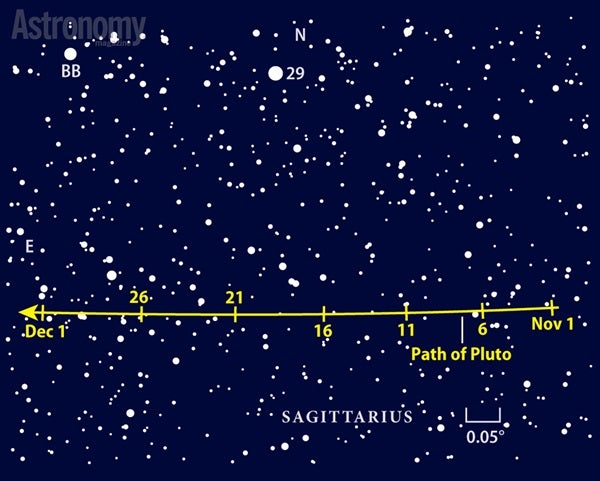

Late June is a great time to hunt for Pluto because it passes close to a 3rd-magnitude star that will guide you right to the spot. Thanks to the New Horizons spacecraft, which flew past in July 2015, this dim dot has now been revealed as an active world of diverse surface features.

So view Pluto with new eyes when it stands 2.7′ due south of Pi (π) Sagittarii on the evening of June 26. You’ll find Pi in northeastern Sagittarius, north of the handle of that constellation’s Teapot asterism. At magnitude 14.1, Pluto is certainly a challenging object, barely visible through an 8-inch scope under a clear dark sky. Many stars of similar brightness lurk in the area, so use a detailed star chart like the one above. Sketch or image the field on consecutive nights and you should be able to identify Pluto as the object that moved.

A telescope nicely shows Neptune’s distinct blue-gray color. At magnifications of 150x or more, you’ll see a 2.3″-diameter disk that confirms it as a planet.

Uranus rises after 3 a.m. local daylight time June 1, but it barely climbs a few degrees high before twilight starts to interfere. You’ll be better off waiting until late in the month to track it down. On the 30th, the planet stands nearly 25° high in the east as dawn starts to paint the sky. It lies in a sparse region of Pisces, some 4° west of 4th-magnitude Omicron (ο) Piscium. Don’t confuse magnitude 5.9 Uranus with a handful of similarly bright stars nearby. Although you can see the planet quite easily through binoculars, you’ll likely need a telescope to confirm a sighting. Only Uranus shows a disk, which spans 3.4″ and glows distinctly blue-green.

Once morning twilight is well underway, you can start searching for Mercury. The innermost planet reaches greatest elongation June 5, when it lies 24° west of the Sun and appears 6° high in the east a half-hour before sunrise. It then shines at magnitude 0.5 and shows up clearly through binoculars. But the planet’s visibility actually improves a bit in the next couple of weeks as it maintains its predawn altitude but grows brighter. On the 15th, Mercury shines at magnitude –0.3, bright enough to see with the naked eye under a haze-free sky. When viewed through a telescope at midmonth, the planet appears 7″ across and slightly more than half illuminated.

Venus remains out of sight all month. It passes on the Sun’s far side from our viewpoint, a configuration known as superior conjunction, on June 6. It will reappear in the evening sky in late July.

When scientists talk about youthful features on the Moon, don’t think these landscapes are actually young. For example, the great floods of molten lava that filled the giant Imbrium impact basin ended about 3 billion years ago. We know that the frenetic bombardment of the inner solar system had quieted down before that, otherwise the lava plains would contain nearly as many craters as other regions do.

An evening after June 12’s First Quarter Moon, the impact crater Timocharis stands out atop Imbrium’s plains north of the lunar equator. And on the 14th, the 19-mile-wide Lambert Crater comes into view, casting a long shadow into Luna’s nightside. Look carefully just south of this crater and you should see the ghostly ring of Lambert R. Scientists suspect that this circular feature is an old crater buried by lava whose peaks barely deform the surface. The gentle slopes show up only at low Sun angles.

The isolated peak of Mons La Hire peeks out of the darkness June 14, catching the Sun’s rays one night before the base experiences sunrise. Lunar scientists William Hartmann and Charles Wood proposed in 1971 that this mountain shares a history with Mons Pico and Mons Piton on Mare Imbrium’s northern side. Giant impacts typically create multiple-ring structures, and this trio of towers marks Imbrium’s tallest ring. Lava buried the rest of this quasi-circular chain, but like Lambert R, it deforms the surface into ridges. One such segment appears northwest of Lambert. This, too, will disappear under a higher Sun, so don’t wait to look for it.

The short nights around the summer solstice are bereft of any major meteor shower, but at least the warm weather makes for comfortable viewing. Although several minor showers populate these June nights, none generates more than a couple of “shooting stars” per hour. You’re more likely to spot a random bit of solar system debris getting incinerated in Earth’s upper atmosphere.

The best time to view these so-called sporadic meteors is in the early morning. We then lie on the part of Earth facing in the direction of its orbital motion, and particles striking the atmosphere tend to shine brighter than those hitting Earth’s trailing side (before midnight). The Moon stays out of the morning sky during the first half of June, so keep watch for a bright rogue meteor as dawn approaches.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mars (south) |

Mars (south) |

Mercury (east) |

| Jupiter (southwest) |

Jupiter (west) |

Saturn (southwest) |

| Saturn (southeast) |

Saturn (south) |

Uranus (east) |

| |

Neptune (southeast) |

|

| |

||

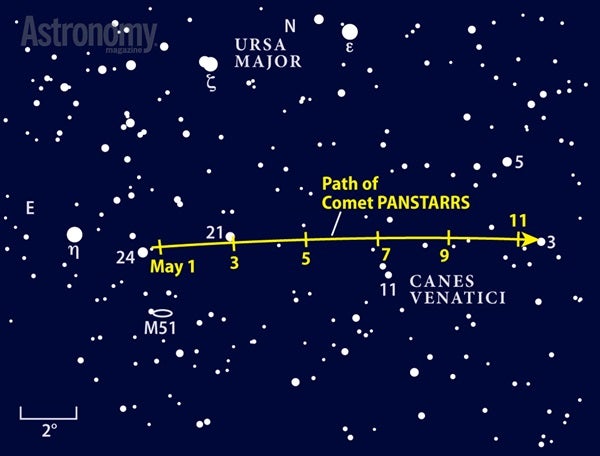

You’ll be in good company while viewing Comet PANSTARRS (C/2013 X1) on June mornings. Keen comet-hunters revel in the hour before dawn, when they scan low in the eastern sky looking for a previously undiscovered quarry. PANSTARRS should glow around 7th or 8th magnitude this month, bringing it within range of binoculars for observers in the southern United States. The comet appears only 10° high as morning twilight begins for those near the Canadian border.

A 7th- or 8th-magnitude dirty snowball usually looks pretty nice through a telescope. This comet’s dust and gas tails spread out from each other, but they tilt away from us at a fairly shallow angle to form a stubby fan. Glare from the Moon interferes with viewing in June’s second half, when PANSTARRS heads even farther south.

Viewers should mark their calendars for Saturday morning, June 4, when the comet’s tails graze the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293). The contrast between PANSTARRS and this photogenic planetary nebula should make for stunning images as well.

Observers who restrict themselves to evening hours get to test their mettle in June with a couple of 11th- or 12th-magnitude possibilities. Check out Comet 81P/Wild as it closes in on the Beehive star cluster (M44) and 9P/Tempel as it caresses Virgo’s face.

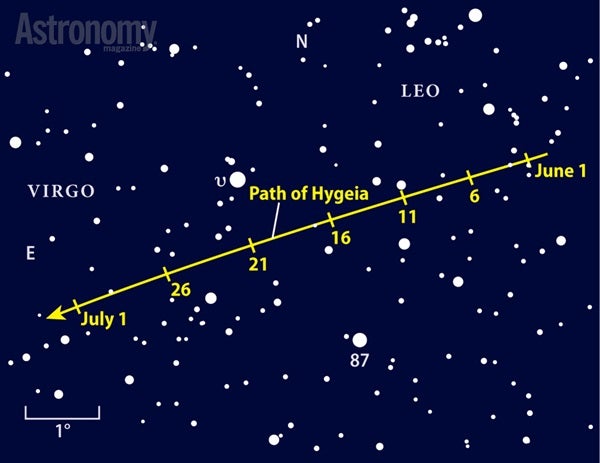

The pickings are pretty slim for asteroid aficionados in June. To achieve success during the early evening hours, rock hounds will have to push their skills and perseverance. As luck would have it, only two asteroids — 7 Iris and 8 Flora — shine as bright as 10th magnitude, and both lie in front of the Milky Way’s center. Slightly fainter 10 Hygeia proves less difficult to spot because it resides against the galaxy’s outer fringes near the Leo-Virgo border.

Take care when jumping to 4th-magnitude Upsilon (υ) Leonis. Although this is the brightest star on the chart below, it’s easy to land on a different star when observing from the suburbs or under bright moonlight. Just because you see a pinpoint near Hygeia’s expected position, it doesn’t mean you have acquired the target. The surefire way to confirm a sighting is to sketch the field with a handful of stars. Come back a night or two later to see which dot has changed position.

With a diameter of 275 miles, Hygeia is the fourth-largest object in the asteroid belt. Astronomers discovered nine others before this one because it is so dark, reflecting 7 percent of the sunlight hitting it.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.