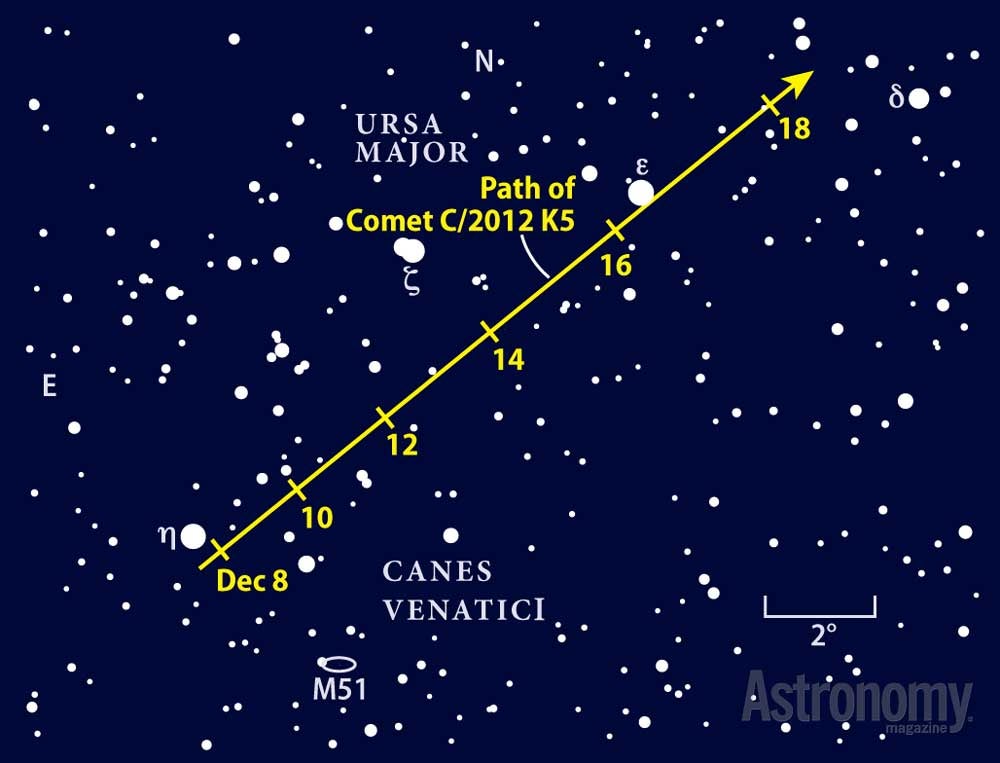

The appearance of Comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) could be a nice addition to the April sky. It should be a fine binocular object when it passes 2° from the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) during the month’s first week. The comet climbs highest shortly after sunset and again before sunrise.

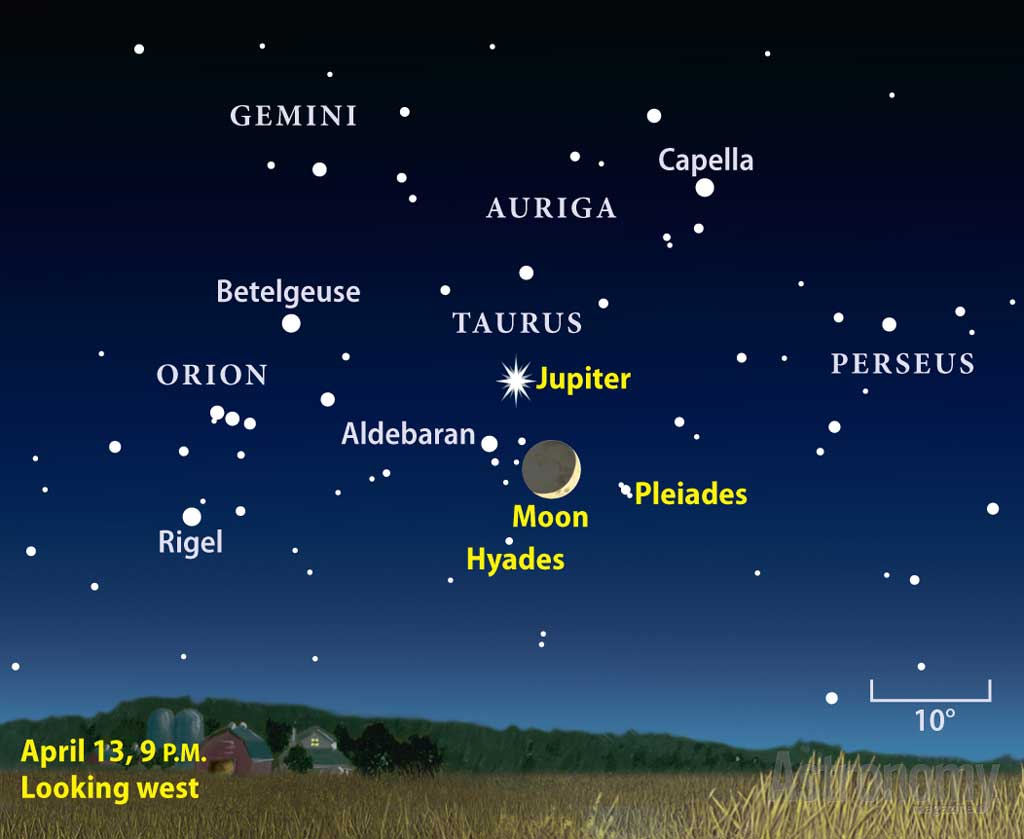

The brightest point of light in the April sky belongs to Jupiter. The giant planet spends the month in Taurus the Bull, to the northeast of the V-shaped Hyades star cluster. By late April, it forms an equilateral triangle with the Bull’s horns — 2nd-magnitude Beta (β) Tauri and 3rd-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Tau. At magnitude –2.0, however, Jupiter blazes

far brighter than either star.

A three-day-old crescent Moon stands between the Hyades and Pleiades star clusters April 13 with Jupiter about 10° above. The following evening, Jupiter and the Moon lie a little more than 2° apart.

The viewing window for Jupiter shrinks noticeably during April. The planet sets after midnight local daylight time early in the month, but it’s gone before 11 p.m. by month’s end. For the best views of the giant world through a telescope, catch it early in the evening when it lies higher in the sky. The planet spans a healthy 35″ in mid-April and will show a wealth of detail in its turbulent atmosphere. Look for an alternating series of parallel dark belts and bright zones — the most obvious features in the jovian cloud tops.

If you don’t see all four at first glance, it means one or more is passing in front of Jupiter’s disk (a transit) or behind it (an occultation). For North American observers, the best satellite action takes place April 2. The planet occults Io starting at 10:40 p.m. EDT and then moves in front of Ganymede commencing at 12:02 a.m. And in the middle of this period (at 11:04 p.m.), Europa begins to transit Jupiter. For much of the night, Callisto will be the only moon visible against a dark sky.

Saturn lies opposite the Sun in our sky the night of April 27/28. Opposition marks an outer planet’s peak because it remains visible all night and also lies closest to Earth, so it shines brightest and appears biggest through a telescope.

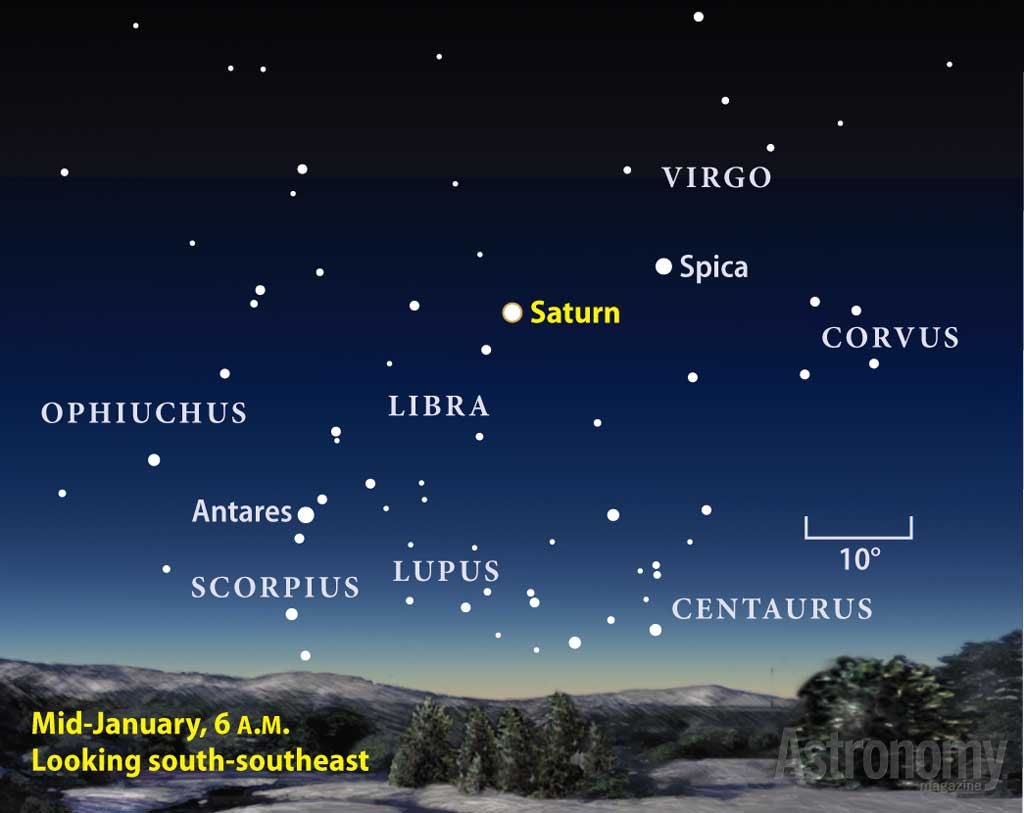

In early April, the ringed planet hangs low in the east-southeast around 10 p.m. local daylight time. Use Spica, Virgo’s 1st-magnitude luminary and already some 15° high, as a guide. Saturn lies 15° east (to the lower left) of Spica among the much fainter background stars of Libra. The magnitude 0.2 planet appears noticeably brighter than Spica. Saturn climbs highest in the south around 3 a.m., when it shows up best through a telescope.

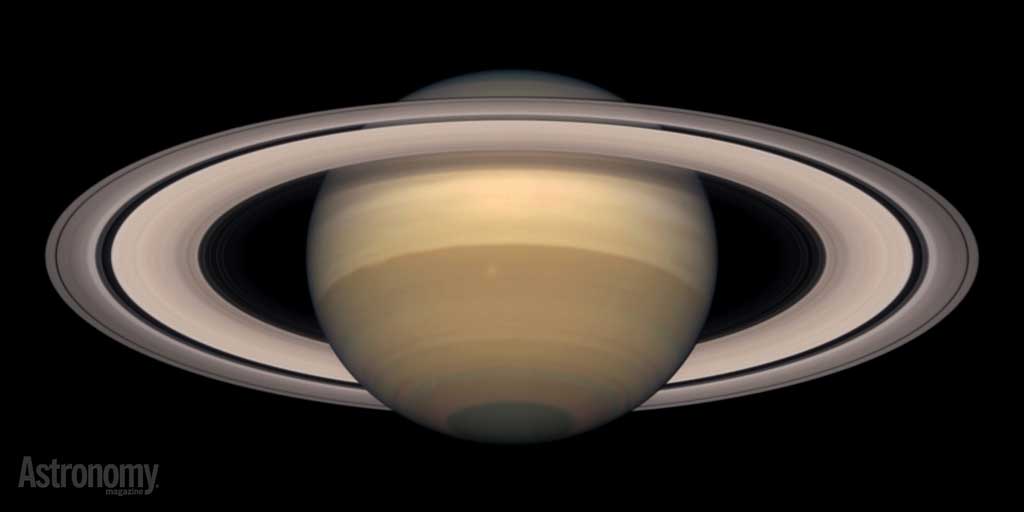

Saturn looks stunning through any telescope. Its disk measures 19″ across the equator at opposition and 17″ from pole to pole. This 10 percent difference shows up quite easily in the eyepiece. Still, there’s no question that the rings dominate any view. They span 43″ and tilt 18° to our line of sight at opposition.

Astronomers label the brightest section of the ring system the B ring. The slightly dimmer one just outside of it is the A ring. The nearly black Cassini Division separates these two broad features.

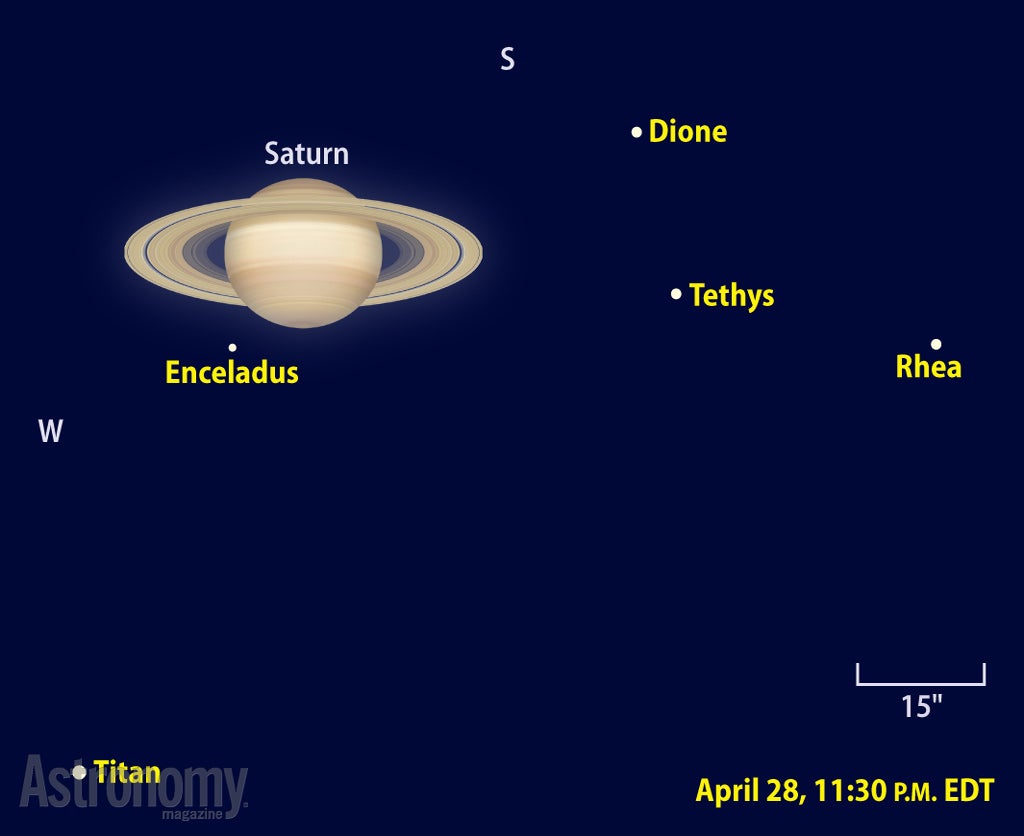

Saturn’s moons offer observers more variety than the four almost equally bright satellites of Jupiter. The ringed world’s brightest is magnitude 8.4 Titan, which shows up easily through any instrument. It orbits Saturn once every 16 days, so it completes nearly two circuits each month. Titan appears closest to Saturn when it swings north or south of the planet. It passes north April 12/13 and 28/29 and south April 4/5 and 20/21.

Perhaps the most intriguing saturnian satellite is Iapetus. This moon’s brightness varies by a factor of five, from magnitude 10.1 to 11.9, as it orbits the planet every 79 days. Iapetus always appears brightest when it lies far west of Saturn and dimmest when it’s far east.

The biggest challenge to finding this moon is that its huge orbit carries it well away from Saturn. Iapetus’ last western elongation occurred March 13, when it stood 10′ from the planet. It passes 2.5′ due north of Saturn the night of April 1/2, when it glows at 11th magnitude. The moon continues to fade as it swings east, reaching greatest elongation April 21/22.

The brightest is magnitude 9.7 Rhea, which orbits Saturn in 4.5 days. It never strays more than 1.4′ from Saturn. Next up is magnitude 10.3 Tethys. With an orbital period of 1.9 days, it always remains within 0.8′ of the planet. Magnitude 10.4 Dione orbits between these two moons. Enceladus is the most challenging moon for most backyard observers. Glowing at magnitude 11.8 and in a 1.4-day orbit that keeps it forever close to the rings, you’ll need a 10-inch scope and good viewing conditions to spot it.

The morning sky brings a fleeting view of Mercury in early April. The innermost planet reached greatest western elongation on the final day of March. For observers at mid-northern latitudes April 1, the magnitude 0.2 object stands 4° high in the east 30 minutes before sunrise. You’ll likely need binoculars to pick it out of the brightening twilight. A waning crescent Moon passes 7° north (to the upper left) of the planet on the 8th.

Neither Venus nor Mars appears in April — both lie too near the Sun. Venus will return to the evening sky in May while Mars waits until June to make a predawn appearance.

Uranus and Neptune are barely visible before dawn in late April. Sixth-magnitude Uranus hangs low in morning twilight; 8th-magnitude Neptune appears about 10° above the southeastern horizon as twilight begins. Both will make more tempting targets in the months ahead.

If you live in Europe, Asia, Africa, or Australia, watch the April 25 Full Moon. Our satellite then passes through the southern edge of Earth’s dark umbral shadow, bringing a minor partial lunar eclipse. When maximum arrives at 20h08m UT, just 1.5 percent of the Moon lies in the shadow.

One glorious sight after another

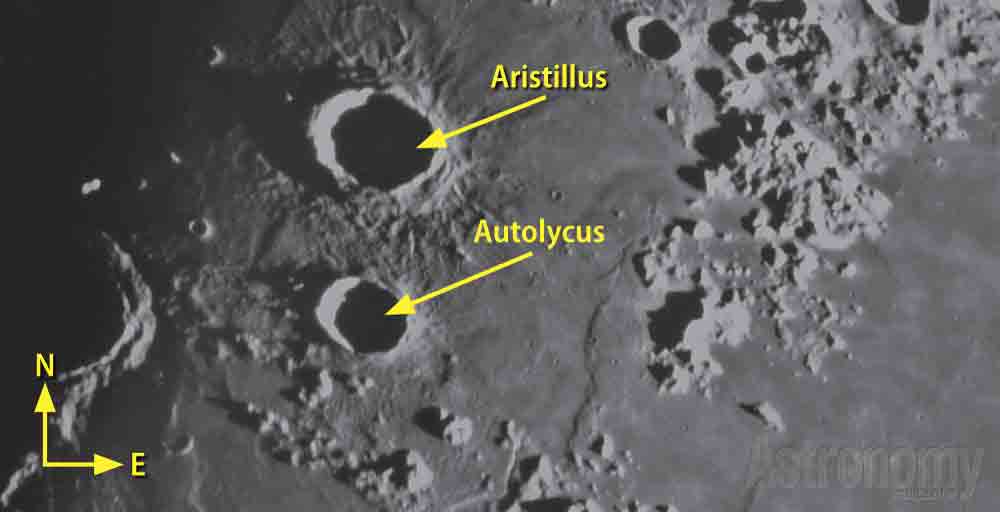

The waxing crescent Moon offers exceptional views in mid-April. A magnificent array of lunar wonders hugs the terminator — the dividing line between night and day where the rising Sun throws features into sharp relief — and changes noticeably from night to night.

On the 17th, just a day before First Quarter phase, the rugged lunar Apennines thrust diagonally into the sunlit domain slightly north of the Moon’s equator. Just north of this mountain range and along the terminator stand two prominent craters — Aristillus and Autolycus — protruding from the flat floor of Mare Imbrium. They formed a couple of billion years ago, near the end of the last major lunar bombardment. Their high walls catch the sunlight on the 17th while their central peaks and floors remain in shadow.

On the next night, the higher Sun angle illuminates the rugged debris apron that splattered out of each of these craters. As you might guess, the larger impact that created Aristillus excavated a lot more material.

Compare the characteristics of these relatively youthful impact scars to the pair of larger round craters Hipparchus and Albategnius just south of the equator. Evidence of their greater age comes from the rounded walls pockmarked with dozens of craterlets.

Observers in the eastern half of North America have a rare opportunity April 17. Great timing allows them to see the Lunar X and Lunar V that Glenn Chaple discussed in “Observing Basics” in the September 2012 Astronomy.

The Lyre plays a sad song

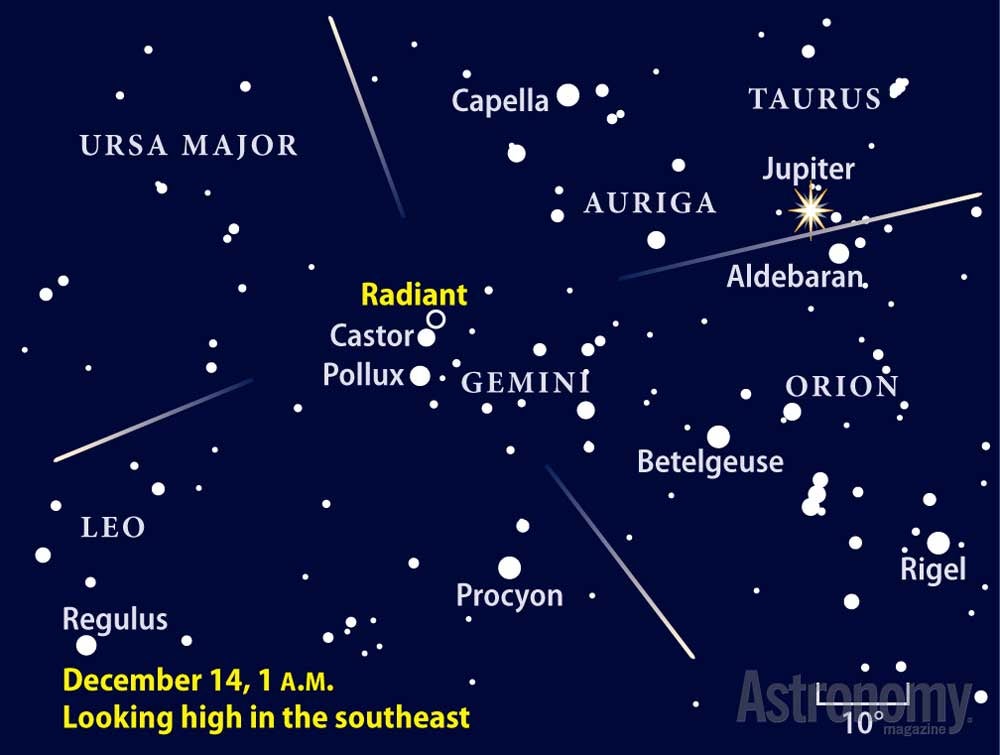

The year’s longest drought for meteor viewing comes between the Quadrantid shower in early January and the April Lyrids. Unfortunately, a bright gibbous Moon interferes at the Lyrids’ peak the morning of April 22. The Moon sets just after 4 a.m. local daylight time, less than a half-hour before twilight begins. Your best observing should come during that brief window.

Plan to head away from the lights of the city and find a location where a building, trees, or a low hill blocks your view toward the western horizon, where the Moon will be. Such a site should give you a decent sky for an hour or so before our dazzling satellite sets.

The Lyrid shower typically produces up to 20 meteors per hour at its peak, but the Moon’s presence likely will cut that number in half. The meteors — streaks of light produced when tiny bits of dust burn up high in Earth’s atmosphere — appear to radiate from a point in Lyra the Lyre. This compact constellation rises as darkness falls and passes through the zenith as dawn starts to break.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Jupiter (west) | Saturn (southeast) | Mercury (east) |

| Saturn (east) | Saturn (southwest) | |

| Uranus (east) | ||

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

A celestial sword sails past a spiral

Many memorable observing sessions have a bright comet floating next to a terrific deep-sky object. And it looks like April may provide another. Comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) may reach 5th magnitude when it passes a few degrees from the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) during the month’s first week. And we have the added fortune of the Moon being out of the way, which brings the great spiral galaxy into view of naked eyes from dark sites.

You can find the pair in the northwest as darkness descends and again in the northeast before dawn. (The finder chart shows the comet’s morning positions because it appears a bit higher then.) PANSTARRS passes 2° west of M31 on April 4 and 5, the best nights for taking wide-angle images. Binoculars will provide superb views for comparing the objects’ sizes, shapes, and characters.

The Andromeda Galaxy appears as an elongated oval that brightens toward the center. Contrast that with the comet’s bright head, or coma, and the tail that spreads out from there. One characteristic shared by the two is a sharply defined edge. The galaxy’s northwest flank, the one closest to the comet, has a prominent dark lane that abruptly ends the glow of M31’s distant suns. For PANSTARRS, the side opposite the spiral galaxy shows a sharp boundary where the Sun’s radiation sweeps up the dust on the comet’s leading edge.

You also should take some closer views through a telescope. Look at the comet’s head for a tiny bright speck, called the false nucleus. The dirty snowball’s real surface lies shrouded within this cocoon of dust. M31’s true core similarly is buried behind a cloud of surrounding stars.

The Moon begins spilling its light into the evening sky after April 15, reducing the contrast between sky and comet. But keep observing on the following nights or make a morning vigil to monitor changes in the tail. By the 26th, the comet likely has faded to 7th magnitude. It then lies in Cassiopeia, about one binocular field east of the bright open star cluster M52.

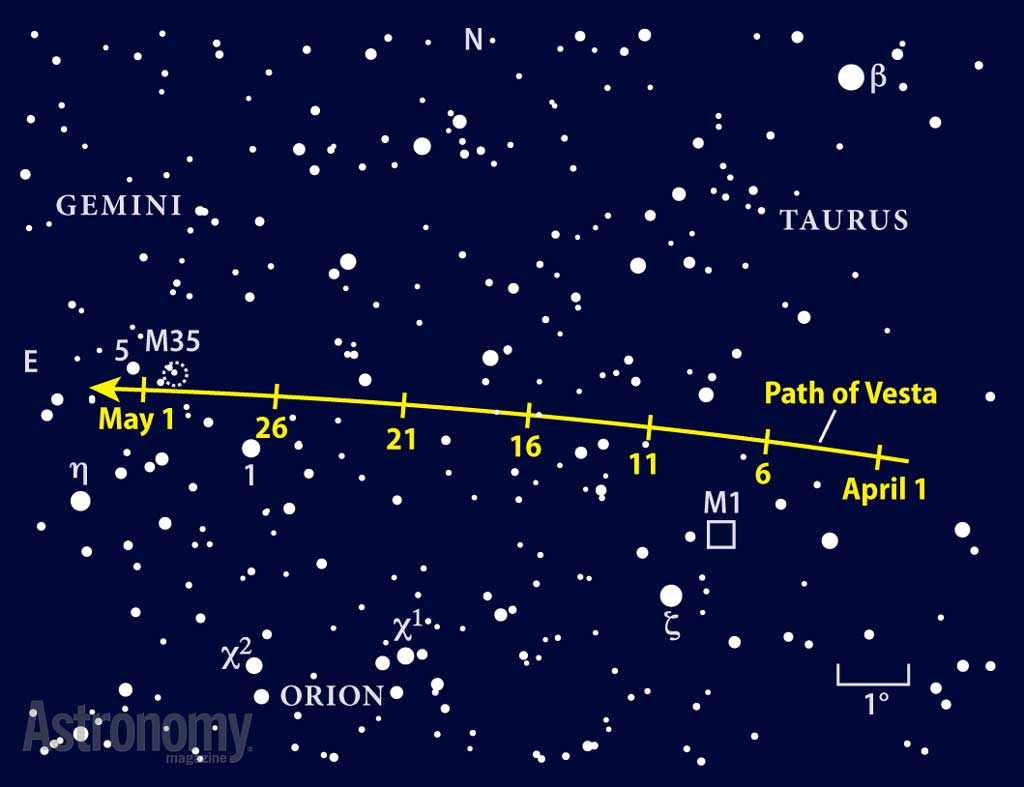

An object fit for the Bull

The sky’s brightest asteroid puts on a good show in April. The best time to track down 4 Vesta comes during the month’s initial week. It then lies in front of some dark, dusty clouds in Taurus that blot out more distant stars in this part of the Milky Way. Glowing at magnitude 8.2, Vesta likely will be out of binocular range if you view from the suburbs, but a 3- or 4-inch telescope will pick it up quite easily.

Start at 3rd-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Tauri, the star marking the tip of the Bull’s southern horn, and then hop to the Crab Nebula (M1), the remnant of a supernova seen on Earth in 1054. Then use the finder chart below to move a little north and west to Vesta’s position.

The next best time to visit Vesta comes in the waning days of April. A great place to start any spring observing session is with the open star cluster M35 in western Gemini. Its bright stars readily punch through the veil of light pollution and make it an attractive sight. Use the nearby 6th-magnitude star 5 Geminorum to help you figure out which way is up in the eyepiece and then carefully make your way over to Vesta. The space rock will be one of the brightest dots visible through the eyepiece.

On the evening of April 29, the magnitude 8.4 asteroid passes directly in front of NGC 2158. This rich open star cluster lies less than 1/2° southwest of M35, but because it lies farther from Earth than its neighbor, it appears smaller and fainter. Vesta takes about two hours to cross NGC 2158, just enough time to watch before they set for the night.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.