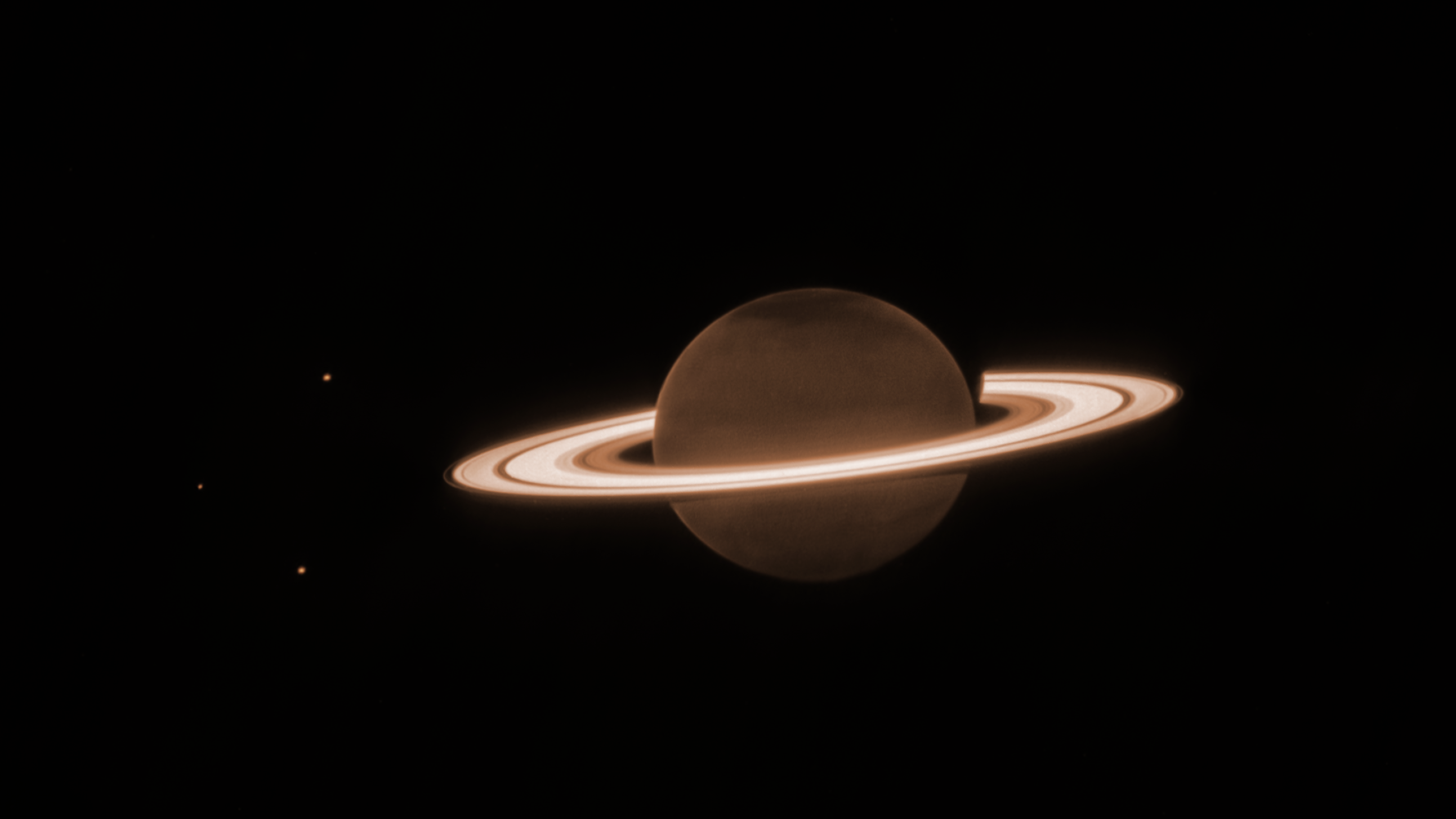

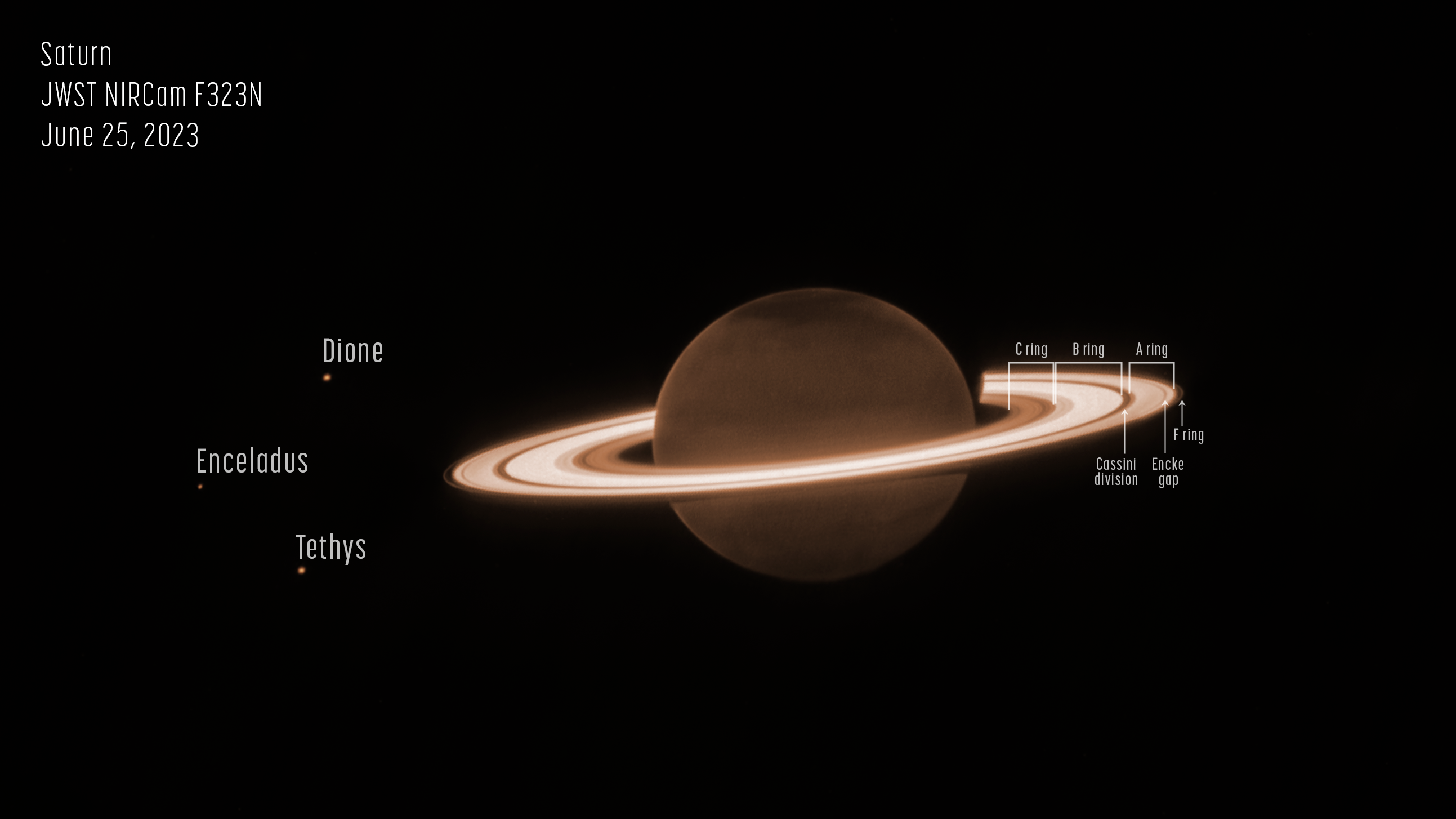

Saturn’s rings are glowing in a new image taken by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The effect is caused by methane gas in Saturn’s atmosphere, which absorbs incoming sunlight and makes the planet appear dark. By contrast, Saturn’s rings lack methane, so they are the standout feature at this wavelength.

The photo, which JWST snapped June 25, is among several taken using the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) as part of the Webb Guaranteed Time Observation program 1247. Such images test JWST’s ability to detect faint moons around the planet — if any new moons are discovered, it will help scientists piece together more of Saturn’s past and gather a complete picture of the current-day saturnian system.

Unique rings

Saturn’s rings consist of pieces of ice and rock ranging in size from a grain of sand to earthly mountains. There are seven main rings around the planet (in order from closest to farthest): D, C, B, A, F, G, and E. Each ring was named in alphabetical order in the sequence they were discovered. At only a few hundred million years old, the rings are young compared to the age of the solar system and may have formed from Saturn’s gravity tearing up one of its moons, or a passing comet or asteroid. Each ring orbits the planet at a different speed.

Other deeper exposures taken with NIRCam allowed researchers to look at some of the planet’s less vibrant rings not seen in this photo, including the G and E rings, the latter of which extends roughly between the orbits of Saturn’s moons Mimas and Titan.

Other details

The photo also shows three of the planet’s icy satellites: Dione, Enceladus, and Tethys. Out of 146 known moons, the three seen in the image appear as red points to the left of Saturn. This year, JWST also discovered a large plume of water vapor jetting from Enceladus that feeds Saturn’s E ring. The plume spans more than 6,000 miles (9,700 kilometers).

Currently, Saturn is experiencing summertime in its northern hemisphere. JWST captured Saturn’s atmosphere in surprising detail at an infrared wavelength of 3.23 microns. This allowed astronomers to view Saturn in ways The Cassini spacecraft could not show, despite its high resolution at other wavelengths. The planet’s familiar stripes are not visible in the near-infrared image because methane- in the upper atmosphere blocks the view of lower clouds.

“We are very pleased to see JWST produce this beautiful image, which is confirmation that our deeper scientific data also turned out well,” said Matthew Tiscareno, a senior research scientist at the SETI Institute, in a press release. “We look forward to digging into the deep exposures to see what discoveries may await.”