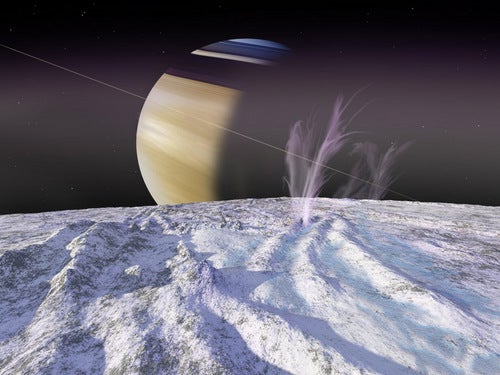

On July 14, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft made its closest flyby yet of a saturnian moon. Swooping within 110 miles (175 kilometers) of Enceladus’ surface, Cassini found a vast cloud of water vapor above the south pole and surprisingly warm fractures from where the gas likely escapes.

Cassini’s magnetometer discovered the moon’s atmosphere on two previous flybys, in February and March. But this time, the spacecraft flew lower and got a much better look. The ion and neutral mass spectrometer found water vapor makes up about 65 percent of the moon’s atmosphere. Molecular hydrogen adds another 20 percent, and the rest comes mainly from carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and molecular nitrogen. The water vapor’s density changes with altitude, suggesting it comes from a local source akin to a geothermal hot spot.

Scientists think the culprit is evaporating surface ice warmed from below. The heat probably comes from tidal energy, the same source that powers the volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io and softens the icy surfaces of Io’s jovian siblings, Europa and Ganymede.

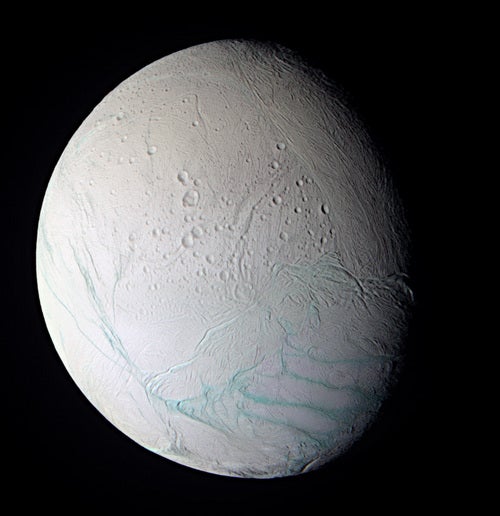

High-resolution images of Enceladus’ south polar region show a younger and more fractured surface than elsewhere on the moon. Icy boulders the size of big houses litter the landscape, but there is little of the fine-grained frost that covers the rest of the moon. Images also reveal several long, bluish cracks, or faults, scientists were quick to dub “tiger stripes.”

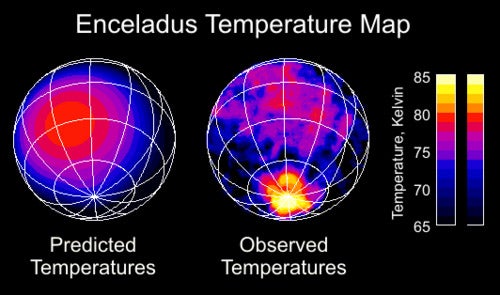

Cassini’s composite infrared spectrometer took a close look at the moon’s temperature and discovered the south pole to be abnormally warm. Near the equator, the mercury tops out at a frigid -316° Fahrenheit (80 kelvins), as expected. The poles should be significantly cooler because the Sun’s rays hit them obliquely, just like on Earth. But the spectrometer found the south polar region averages a rather balmy –307° F (85 kelvins). Even more surprising: Some spots concentrated near the tiger stripes push the temperature up to –261° F (110 kelvins).

Obviously, sunlight isn’t the only heat source at Enceladus. Most likely, heat escapes through the surface in the polar region, and in particular around the tiger stripes. The warmed ice then evaporates, releasing the water vapor detected by the other instruments.

How the small moon generates so much internal heat — and why it should be concentrated at the south pole — remain mysteries. Mission scientists hope to tease out more clues during Cassini’s years-long exploration of the saturnian system.