N ASA’s Cassini spacecraft has, for the first time, revealed surface details of Saturn’s moon Hyperion, including cup-like craters filled with hydrocarbons that may indicate a more widespread presence in our solar system of basic chemicals necessary for life.

Hyperion yielded some of its secrets to the battery of instruments aboard Cassini as the spacecraft flew close by in September 2005. Water and carbon dioxide ices were found, as well as dark material that fits the spectral profile of hydrocarbons.

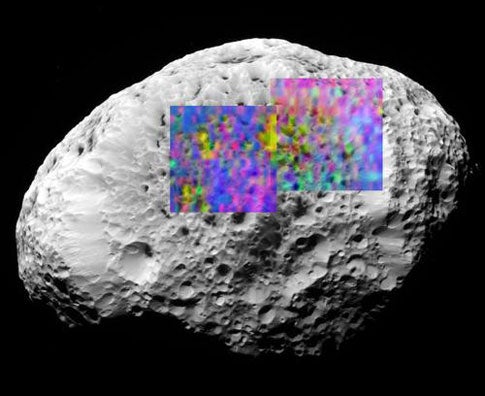

Hyperion’s surface craters and composition were observed during this flyby, including keys to understanding the moon’s origin and evolution over 4.5 billion years. This is the first time scientists were able to map the surface material on Hyperion.

“Of special interest is the presence on Hyperion of hydrocarbons -combinations of carbon and hydrogen atoms that are found in comets, meteorites, and the dust in our galaxy,” said Dale Cruikshank, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and the paper’s lead author. “These molecules, when embedded in ice and exposed to ultraviolet light, form new molecules of biological significance. This doesn’t mean that we have found life, but it is a further indication that the basic chemistry needed for life is widespread in the universe.”

Cassini’s ultraviolet imaging spectrograph and visual and infrared mapping spectrometer captured compositional variations in Hyperion’s surface. These instruments, capable of mapping mineral and chemical features of the moon, sent back data confirming the presence of frozen water found by earlier ground-based observations, but also discovered solid carbon dioxide (dry ice) mixed in unexpected ways with the ordinary ice. Images of the brightest regions of Hyperion’s surface show frozen water that is crystalline in form, like that found on Earth. “Most of Hyperion’s surface ice is a mix of frozen water and organic dust, but carbon dioxide ice is also prominent. The carbon dioxide is not pure, but is somehow chemically attached to other molecules,” explained Cruikshank.

Prior spacecraft data from other moons of Saturn, as well as Jupiter’s moons Ganymede and Callisto, suggest that the carbon dioxide molecule is “complexed,” or attached with other surface material in multiple ways. “We think that ordinary carbon dioxide will evaporate from Saturn’s moons over long periods of time,” said Cruikshank, “but it appears to be much more stable when it is attached to other molecules.”

“The Hyperion flyby was a fine example of Cassini’s multi-wavelength capabilities. In this first-ever ultraviolet observation of Hyperion, the detection of water ice tells us about compositional differences of this bizarre body,” said Amanda Hendrix, Cassini scientist on the ultraviolet imaging spectrograph at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Hyperion, Saturn’s eighth largest moon, has a chaotic spin and orbits Saturn every 21 days.