“A foundational tenet of relativity is what physicists call Lorentz invariance,” said Floyd Stecker from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “This includes the notion that light traveling in a vacuum sets a cosmic speed limit that cannot be exceeded by any matter or information.”

But some versions of theories designed to replace general relativity, such as string theory and loop quantum gravity, predict possible exceptions. The highest-energy neutrinos offer a way to determine how big any faster-than-light loophole may be.

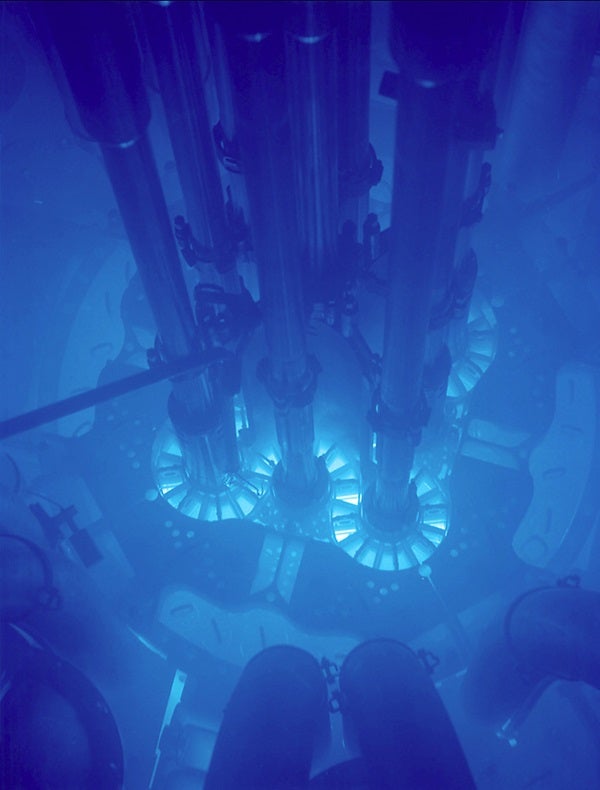

Neutrinos are among the least understood fundamental particles. Each second, about 100 trillion of them pass through our bodies, but they interact with matter so infrequently that even at this rate catching a single event in a human-sized detector would take decades. Neutrinos are produced in Earth’s atmosphere by the impact of cosmic rays and through nuclear reactions in the center of the Sun. They were produced in the Big Bang and are emitted by exploding stars, pulsars, black holes, and other astrophysical phenomena. Unlike charged particles, such as protons in cosmic rays, neutrinos are not deflected by interstellar magnetic fields. They easily escape places light cannot, such as the core of a collapsing star, and they are rarely absorbed or scattered by intervening matter, zipping through the universe almost completely unimpeded.

Experiments have shown neutrinos come in at least three varieties, called “flavors,” and that they switch from one flavor to another as they travel, a discovery that won this year’s Nobel Prize in physics. Recent findings based on cosmological observations estimate the combined mass of all three flavors at less than a millionth the mass of a single electron. Yet, according to relativity, having even a small amount of mass means neutrinos should travel slower than light speed. But do they?

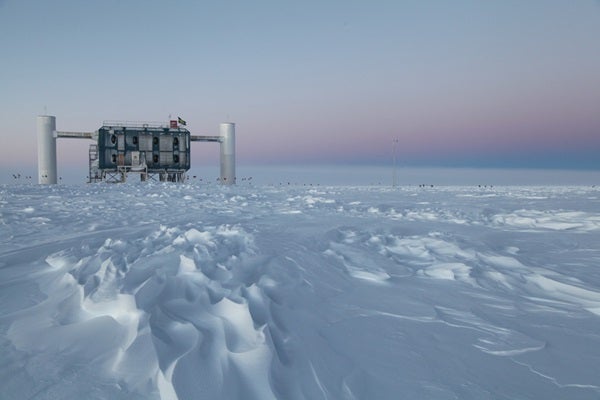

In 2011, an experiment designed to measure the speed of neutrinos erroneously suggested they traveled slightly faster than light. The incident intrigued Stecker, who began thinking about the physical consequences of faster-than-light, or superluminal, neutrinos and how their effects could be observed in planned and existing experiments, such as the IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica.

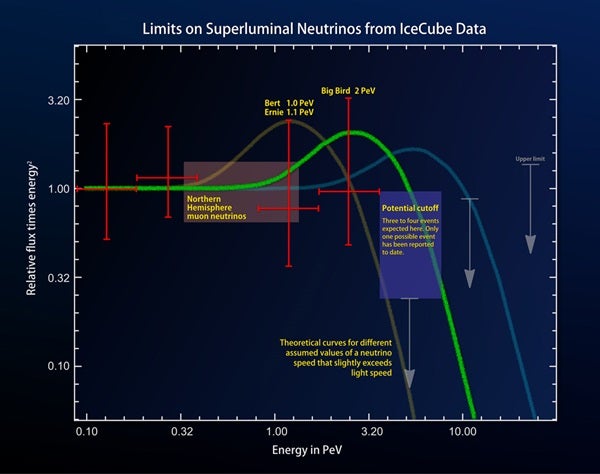

In November 2013, the scientific collaboration operating IceCube announced strong evidence the facility had detected dozens of high-energy neutrinos coming from beyond the solar system. These included two events, nicknamed Bert and Ernie, with energies of about 1 quadrillion electron volts (PeV). In 2014, another extreme event, dubbed Big Bird, arrived with an energy of about 2 PeV.

“That’s about the energy needed to lift a roll of postage stamps a foot off the ground,” Stecker said, “yet it’s contained in a subatomic particle with the smallest mass known.”

Big Bird was followed in July 2015 by a neutrino with an estimated energy of 2.6 PeV. These are the highest-energy neutrinos ever detected. They appear to originate outside our galaxy, but the astronomical objects producing them are presently unknown.

Using IceCube observations, Stecker and his colleagues were able to place strong limits on how much faster than light any superluminal neutrinos can be. That’s because faster-than-light neutrinos will lose energy in their intergalactic travels through several exotic mechanisms. This results in a characteristic “bump” of lower-energy neutrinos and a sharp cutoff at higher energies. “Above a certain threshold energy, which depends on their velocity, faster-than-light neutrinos will emit pairs of subatomic particles, including other neutrinos,” said Stecker. This creates a pileup of neutrinos around the threshold energy — the bump — and an absence of neutrinos at higher energies — the cutoff.

Researchers calculated “bump-and-cutoff” curves for slightly different superluminal neutrino speeds and compared them to the most energetic IceCube events. Stecker has since refined this analysis by including additional detections announced in August.

It would take the discovery of many more extragalactic neutrinos to reveal a pronounced pileup. But if both features ultimately are observed, they would provide strong evidence that neutrinos violate Lorentz invariance.

“Even with no observed pileup below the cutoff, the very existence of high-energy neutrinos can be used to determine the strongest upper limit on their velocity yet found,” Stecker said. “So our results allow for either only a very, very small violation of relativity or give strong indications that Einstein’s theory is upheld.”

The value Stecker and colleagues obtained, five parts in a billion trillion, gives the relative amount by which the velocity of neutrinos can exceed the speed of light. This relative excess is more than 100 billion times lower than that found from studying the arrival of neutrinos from SN 1987A, a supernova in the nearby galaxy known as the Large Magellanic Cloud. Stecker also notes that if the IceCube experiment detects neutrinos at even higher energies, it would leave even less wiggle room for neutrinos having superluminal velocities.

Francis Halzen from the University of Wisconsin-Madison is intrigued by the study. “I find it amazing that each time we detect a higher-energy event, we actually improve the precision on a fundamental measurement,” he said.

Whether or not neutrinos are breaking Einstein’s cosmic speed limit, they’re definitely ushering in a new astronomical era. Historically, light has been astronomy’s only courier. Now neutrinos deliver information about the most extreme events in the universe completely independent of the electromagnetic spectrum.

“It’s the dawn of extragalactic neutrino astronomy,” said Stecker, “and we’re only now learning how to decipher the message.”