A proposed definition of “planet” that would let Pluto remain one and also add three objects — including Pluto’s largest moon — was roundly defeated in a poll during the first debate on the plan. The discussion, restricted to planetary scientists, took place yesterday at the International Astronomical Union’s (IAU) General Assembly meeting in Prague.

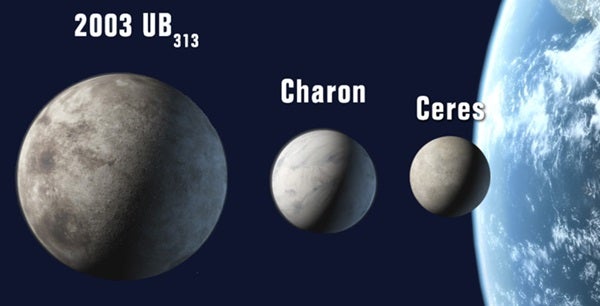

Under the proposal, a planet would be any object that orbits a star, is neither a star itself nor the moon of another planet, and contains enough matter that gravity forces it into a nearly round shape. If the resolution passes a vote on August 24, Pluto would make the cut. But so would Pluto’s largest moon, Charon; Ceres, the largest asteroid; and the Kuiper Belt object nicknamed Xena (officially, 2003 UB313).

In addition, Pluto, Charon, and Xena would form a new class of objects called “plutons,” and the term “minor planet” would fade from astronomy’s lexicon. Objects not classified as planets would simply be referred to as “small solar system bodies.”

The chief objection to this definition, which contains four paragraphs and as many footnotes, is that students and the public would find it too hard to grasp. “This is really not a burning issue for most astronomers,” says William Blair of Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University. “It really is a classification problem more than an issue of science.”

“The universe is too complex and too fascinating to fit everything into neatly described categories,” observed Paul Weissman, a comet expert at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, during the debate. “Anally pursuing such a goal is stamp collecting, not science.” His suggestion: “Grandfather in” Pluto’s planethood and class Xena and other similar-sized objects as plutons.

University of Hawaii astronomer David Tholen took a different stance. He argued for defining “planet” based simply on an object’s brightness. Any body brighter than an absolute magnitude of zero would qualify. This would exclude Ceres (3.3) but retain Pluto (–1) and induct Xena (–1.1) and another Kuiper Belt object — 2005 FY9 (–0.4) — into the planet club. However, scientists weren’t polled on these ideas.

On Thursday, the American Astronomical Society’s 1,300-member Division of Planetary Sciences issued a statement urging astronomers to adopt the original definition. But in a test vote conducted Friday, only an estimated 25 percent of planetary scientists backed the plan.

Many said they had difficulty with the plan’s subtle redefinition of “satellite” that lets Charon graduate to planetary status. At just over half Pluto’s size, Charon is so big that the pair’s center of mass lies outside Pluto — the only such case in the solar system.

“From what I can tell, they have tried to come up with a consistent definition,” Blair says. “Then they are apparently willing to … allow Charon to itself be called a planet, with Pluto and Charon being a ‘double planet’ system. This goes too far.”

Alan Boss at the Carnegie Institution of Washington says the plan allows too great a mass range for planets. There’s a factor of 10 billion between the smallest planet defined and 13 Jupiter-masses, the upper limit where astronomers generally agree planets end and substellar objects begin. “Not even stars have such a mass range,” Boss tells Astronomy. “You’d think science could afford a better focus.”

The gathered scientists reacted far more favorably to a new planet-definition presented Friday by Julio Fernández of the University of the Republic in Montevideo, Uruguay. The proposal, signed by 17 astronomers from nine nations, would demote Pluto and give us a solar system with eight planets.

“I much prefer the competing second proposal to the original,” says Boss, who is headed to Prague. Nearly 75 percent of the scientists polled during Friday’s debate felt the same way.

While both definitions argue that a planet must be nearly round in shape, Fernández’s version adds that it must also be “by far the largest object in its local population” and “not produce energy by any nuclear fusion mechanism.” This last point solidifies the distinction between gas-giant planets and brown dwarf stars, which can undergo a flicker of fusion while young.

“Pluto, Ceres, and other large trans-neptunian objects … should be not considered as planets, since they never were the dominant bodies in their accretion zones,” reads the new plan.

That would be fine with Paul Weissman. “The correct definition of a planet that I would offer is that it is a body orbiting a star that is massive enough to clear its dynamical zone of debris (asteroids and comets) over the history of the solar system,” he commented. “This definition is intrinsic to each planet and to its unique position in the solar system.”

Other scientists agree that dynamics must play a role in any definition of a planet. On Wednesday, Steven Soter of New York’s American Museum of Natural History submitted a paper to The Astronomical Journal that argues a planet can be defined by the degree to which it dominates other masses that share its orbital zone. His analysis shows that eight planets — Mercury through Neptune — affect nearby objects 100,000 times more than Ceres, Xena, or Pluto and Charon.

There was one area of broad consensus during Friday’s discussion: Nearly everyone hates the term pluton.

Allen Glazner, a geology professor at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, took the IAU to task for swiping a well-established geological term. The word refers to a body of igneous rock formed beneath a planetary surface.

“Planetology is close enough to geology that there is potential for serious and endless confusion here if the astronomers stick with this decision,” says Glazner. “What happens when we find a pluton on a pluton?”

Scientists will continue debating the resolution Tuesday. The IAU’s planet-definition committee may refine its proposal before Thursday’s vote among the meeting’s 2,500 astronomers.