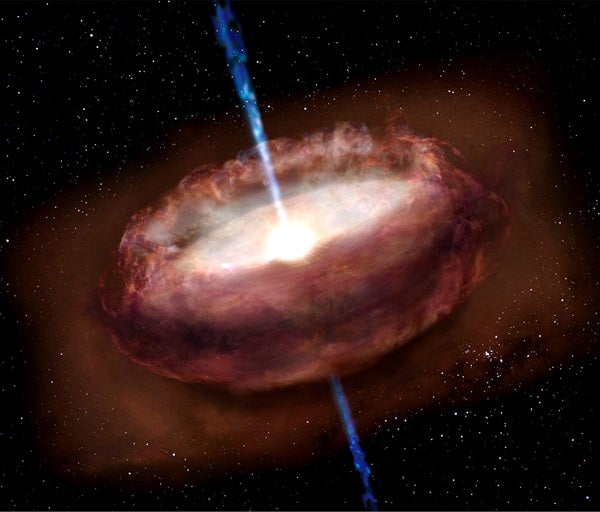

Since 2009, the five-year SEEDS Project has focused on direct imaging of exoplanets — planets orbiting stars outside our solar system — and disks around a targeted total of 500 stars. Planet formation, an exciting and active area for astronomical research, has long fascinated many scientists. Disks of dust and gas that rotate around young stars are of particular interest because astronomers think that these are the sites where planets form — in these so-called “protoplanetary disks.” Since young stars and disks are born in molecular clouds, giant clouds of dust and gas, the role of dust becomes an important feature of understanding planet formation; it relates not only to the formation of rocky, Earth-like planets and the cores of giant Jupiter-like planets but also to that of moons, planetary rings, comets, and asteroids.

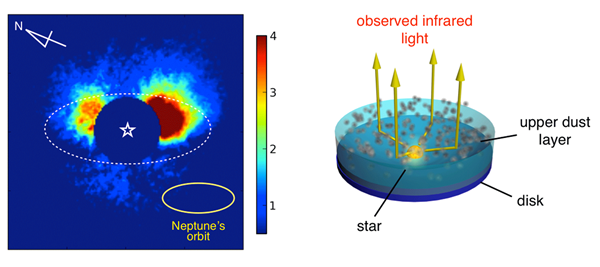

As a part of the SEEDS Project, the current team of researchers used HiCIAO to observe a possible planet-forming disk around the young star RY Tauri. This star is about 460 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Taurus and is around half a million years old. The disk has a radius of about 70 astronomical units (1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance, or about 93 million miles [150 million kilometers]), which is a few times larger than the orbit of Neptune in our own solar system.

Astronomers have developed powerful instruments to obtain images of protoplanetary disks, and Subaru Telescope’s HiCIAO is one of them. HiCIAO uses a mask to block out the light of the central star, which may be a million times brighter than its disk. Researchers can then observe light from the star that has been reflected from the surface of the disk. The scattered light will reveal the structure of the surface of the disk, which is very small in scale and difficult to observe, even with large telescopes. Observers use HiCIAO with a 188-element adaptive optics system to reduce the blurring effects of the Earth’s atmosphere, making the images significantly sharper.

Changes in structure perpendicular to the surface of a disk are much harder to investigate because there are few good examples to study. Therefore, the information about vertical structure that this image provides is a contribution to understanding the formation of planets, which depends strongly on the structure of the disk, including spirals and rings, as well as height.

The team performed extensive computer simulations of the scattered light, for disks with different masses, shapes, and types of dust. They found that the scattered light is probably not associated with the main surface of the disk, which is the usual explanation for the scattered light image. Instead, the observed infrared emission can be explained if the emission is associated with a fluffy upper layer, which is almost transparent. The team estimated the dust mass in this layer to be about half the mass of Earth’s Moon.

Why is this fluffy layer observed in this disk, but not in many other possible planet-forming disks? The team suspects that this layer is a remnant of the dust that fell onto the star and the disk during earlier stages of formation. In most stars, unlike RY Tau, this layer dissipates by this stage in the formation of the star, but RY Tau may still have it because of its youth. It may act as a special comforter to warm the inside of the disk for baby planets being born there. This may affect the number, size, and composition of the planets being born in this system.

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a superb international millimeter/submillimeter telescope, will soon be making extensive observations of protoplanetary disks, which will allow scientists to directly observe ongoing planet formation in the midplane of a disk. By comparing SEEDS and ALMA observations scientists may be able to understand the details of how planets form, something that has raised fascinating questions for centuries.