Scientists have detected giant twisting waves in the lower atmosphere of the Sun. This discovery sheds light on the mystery of the Sun’s corona (the region around the Sun) having a vastly higher temperature than its surface. These findings will help us understand more about the turbulent solar weather and its affect on Earth.

The massive solar twists, known as Alfven waves, were discovered in the lower atmosphere with the Swedish Solar Telescope in the Canary Islands by scientists from Queen’s University Belfast, United Kingdom, the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom, and California State University Northridge.

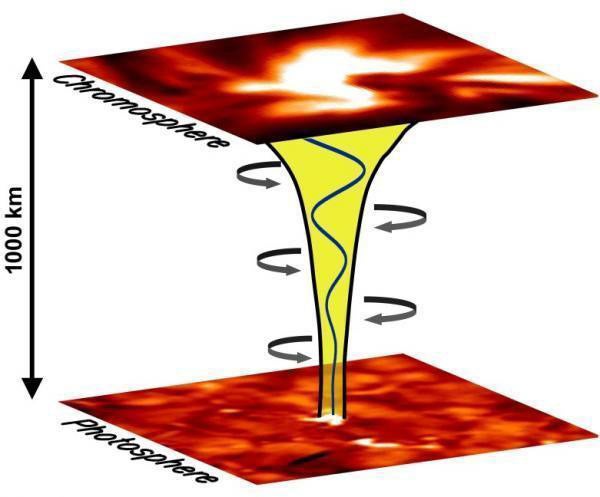

The increase in solar temperature from approximately 10,800° Fahrenheit (6,000° Celsius) on the visible surface of the Sun (photosphere) to well over a million degrees in the higher overlaying solar corona, has remained at the forefront of astrophysical research for more than half a century. The new observations reveal the process behind this phenomenon, whereby these unique magnetic oscillations spread upward from the solar surface to the Sun’s corona with an average speed of more than 43,200 miles (70,000 kilometers) per hour, carrying enough energy to heat the plasma to well over a few million degrees.

“Understanding solar activity and its influence on the Earth’s climate is of paramount importance for human kind,” said Professor Mathioudakis, the leader of he Queen’s University Belfast Solar Group. “The Sun is not as ‘quiet’ as many people think. The solar corona, visible from Earth only during a total solar eclipse, is a very dynamic environment that can erupt suddenly, releasing more energy than 10 billion atomic bombs. Our study makes a major advancement in the understanding of how the million-degree corona manages to achieve this feat.”

Alfven waves are caused by the twisting of structures in the Sun’s atmosphere and can be detected by the periodic velocity signals emitted. The Alfven waves detected in this study were found to be associated with a large magnetic field concentration on the surface of the Sun, approximately twice the size of the British Isles. These strong magnetic fields manifest as bright features, often with lifetimes exceeding one hour. The Swedish Solar Telescope is the largest solar telescope in Europe and produces some of the sharpest images currently available. Bearing in mind that the Sun is 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) away, the measurements carried out are equivalent to reading the time on Big Ben in London from Tokyo.

“Often, waves can be visualized by the rippling of water when a stone is dropped into a pond, or by the motions of a guitar string when plucked,” said Dr. David Jess from Queen’s University Belfast and lead author of the science paper. “However, Alfven waves cannot be seen so easily. In fact, they are completely invisible to the naked eye. Only by examining the motions of structures and their corresponding velocities in the Sun’s turbulent atmosphere could we find, for the first time, the presence of these elusive Alfven waves.”

“The heat was on to find evidence for the existence of Alfven waves,” said Professor Erdelyi, head of the Solar Physics and Space Plasma Research Center (SP2RC), who led the theoretical interpretation of Alfven waves. “International space agencies have invested considerable resources trying to find purely magnetic oscillations of plasmas in space, particularly in the Sun. These waves, once detected, can be used to determine the physical conditions in the invisible regions of the Sun and other stars, through the technique of magneto-seismology. It was a real thrilling experience to interpret the data found by my colleagues at Queen’s University.”

“These are extremely interesting results,” said Professor Keith Mason, CEO of the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC). “Understanding the processes of our Sun is incredibly important as it provides the energy which allows life to exist on Earth and can affect our planet in many different ways. This new finding of magnetic waves in the Sun’s lower atmosphere brings us closer to understanding its complex workings and its future effects on the Earth’s atmosphere.”