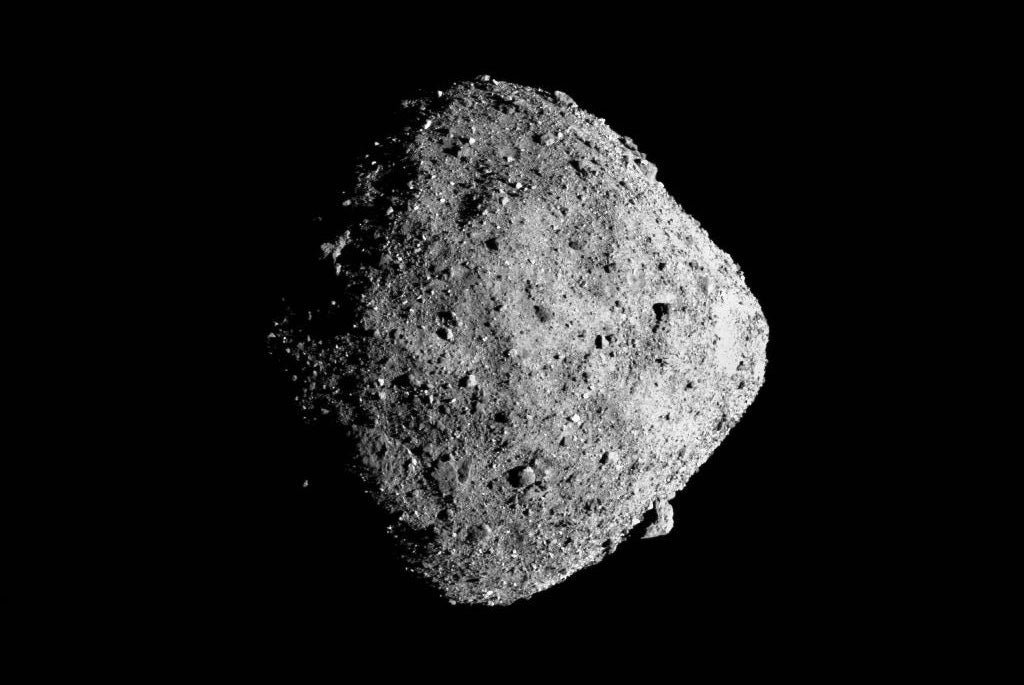

The OSIRIS-REx spacecraft returned triumphantly to Earth in 2023 after collecting 4.3 ounces (121.6 grams) of precious grains of dust and rock from the asteroid Bennu in 2020. While that sample return was an incredible feat of engineering, its arrival on Earth was just the beginning of the scientific adventure.

On Jan. 29, NASA held a press conference to announce findings by two teams studying the Bennu samples. Detailed in two Nature papers released the same day, the grains reveal that Bennu held a wealth of amino acids, including 14 of the 20 that make up biological proteins – the material that makes up living things. While none of these discoveries counts as life in itself, they are the molecules that life uses to build itself. Their existence heavily strengthens the theory that such materials were delivered to Earth by asteroids such as Bennu.

Scientists also revealed the discovery of clays and brines, substances that only occur with the slow evaporation of water. This informs the history of water in the solar system, and especially the interplay of water and the molecules needed for life.

Nicky Fox, associate administrator of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters, said in a press release that, “Asteroids provide a time capsule into our home planet’s history, and Bennu’s samples are pivotal in our understanding of what ingredients in our solar system existed before life started on Earth.”

A prelude to life

Bennu, like other asteroids, provides a window into the early solar system. For scientists, these space rocks are pristine environments, untouched by the complicated cycles of weather, water, rock, and more that take place on planets and moons. They can reveal the materials present in the solar system’s early days, and a simplified history of how those materials came to be.

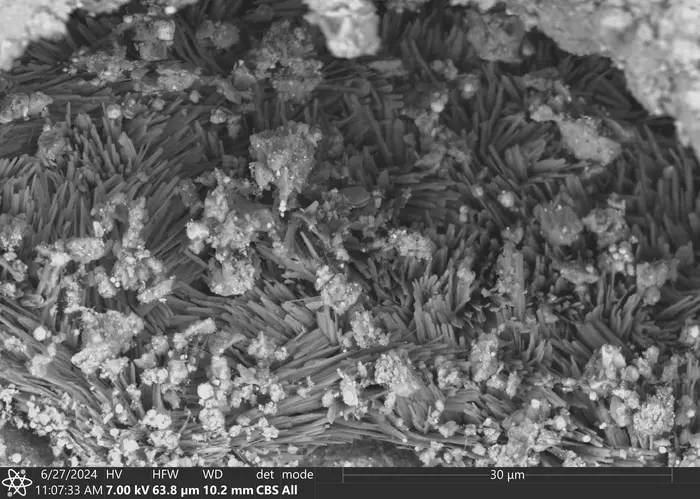

In addition to the 14 biological amino acids, the samples from Bennu also contained 19 more non-biological amino acids, as well as the five nucleobases that make up RNA and DNA. The team also found a surprising amount of ammonia, which reacts with formaldehyde, also present on Bennu, to create many amino acids, giving a neat picture of how the abundance of materials came to be. The wealth of complex chemistry, including the chemical components necessary for life, make the Bennu samples a powerful tool for investigating how life arose.

“Data from OSIRIS-REx adds major brushstrokes to a picture of a solar system teeming with the potential for life,” said Dworkin. “Why we, so far, only see life on Earth and not elsewhere — that’s the truly tantalizing question.”

Another major discovery from the Bennu samples were briny materials that form as water evaporates. Asteroids like Bennu’s parent body probably formed directly from the accumulation of icy rocks. At some point, that ice must have melted, as water is necessary to form many of the materials found on Bennu. But the brines show that the water also then evaporated. Perhaps counterintuitively, this loss of water was also important: It was only as the water disappeared that some of the chemistry became possible to create the materials that one day might be incorporated by life.

A careful investigation

None of this analysis would have been possible without a sample-return mission — or if the samples been compromised. OSIRIS-REx had the challenging task of removing samples from Bennu and transporting them to Earth. But scientists had a different but equally challenging task once they arrived: not letting Earth’s atmosphere affect that time capsule of space rock.

Tim McCoy, curator of meteorites at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C., and lead author of one of the Nature papers released today, pointed out that especially when studying the history of water, any contamination of water vapor would have rendered their studies impossible. The history of water in the solar system is knowable only because of the careful curation of the asteroid samples.

The samples were removed from the spacecraft’s return assembly in a clean glove box, with no exposure to outside air. The sample container was pumped full of nitrogen, an inert gas. The samples are now divided between a bevy of institutions, partially to acknowledge the international effort that went into the mission, and partly so that no single accident can destroy all the samples.

The Apollo lunar missions likewise returned a wealth of samples. Thanks to their careful preservation, scientists are still able to experiment on lunar samples, despite the 50-plus years since the end of Apollo.

Jason Dworkin, OSIRIS-REx project scientist, pointed out that the majority of the Bennu sample is still unexplored. With the same careful curation as the Apollo samples, scientists will be able to unearth new discoveries for decades to come.

“The clues we’re looking for are so minuscule and so easily destroyed or altered from exposure to Earth’s environment,” said Danny Glavin, one of the co-authors. “That’s why some of these new discoveries would not be possible without a sample-return mission, meticulous contamination-control measures, and careful curation and storage of this precious material from Bennu.”

Left-handed life

Out of any great scientific discovery come not just answers, but more questions. One of the biggest questions offered by the Bennu samples involves the “handedness” of molecules. Many molecules are chiral, meaning their shape can take one of two mirrored forms, left-handed or right-handed. Life as we know it vastly prefers left-handed molecules, and has evolved to use and produce them. Scientists don’t know why, but have postulated that an over-abundance of left-handed molecules on early Earth might have given rise to this preference.

But Bennu’s samples had an equal abundance of left- and right-handed molecules. If Bennu is indeed representative of the asteroids that delivered the ingredients for life, then the question of why life prefers lefties is still a mystery.