Key Takeaways:

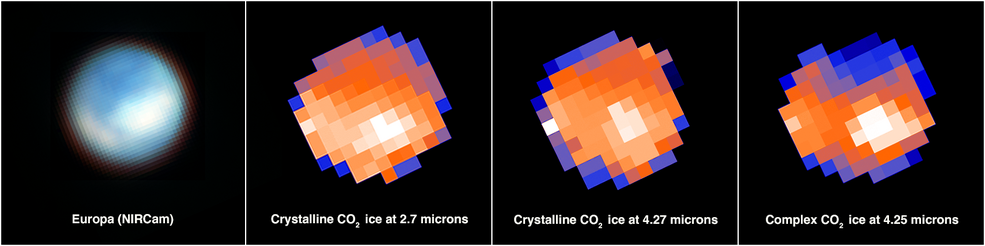

In the last few weeks of September 2023, two teams of scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) discovered the presence of carbon dioxide (CO2) on the surface of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa. This discovery could have implications for the search for life elsewhere in the universe.

The find was highlighted by two studies released on September 21 and originating from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland and Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. It shows CO2 ice on the surface of Europa in a region of “chaos terrain,” or an area marked by geologically disrupted and relatively young material. This region, called Tara Regio, spans roughly 1,800 square kilometers, and the CO2 ice there seems to have originated from the subsurface ocean scientists believe Europa hides beneath its icy crust.

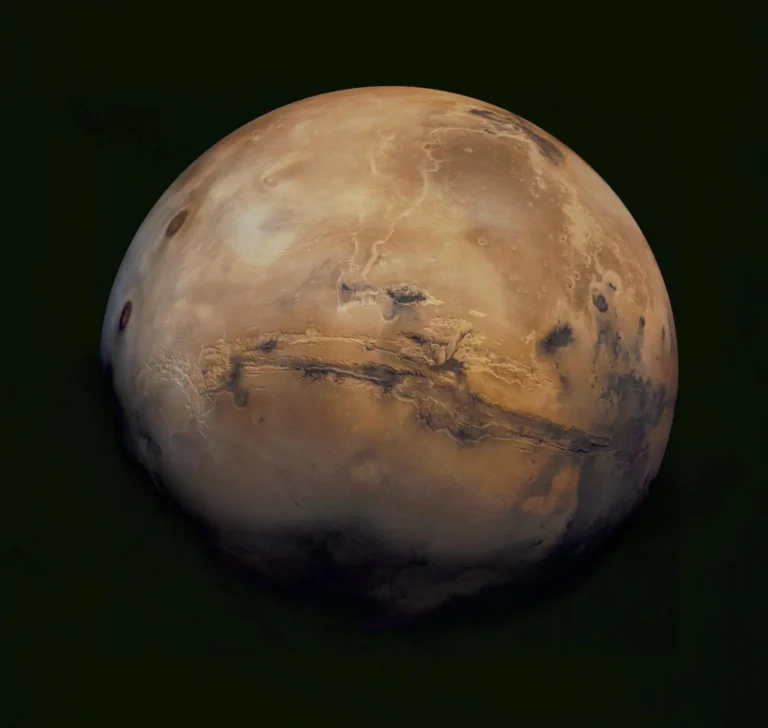

The idea that Europa harbors a hidden ocean of liquid water beneath an outer shell of ice dates back to the 1970s, when data coming in from the Voyager spacecraft showed that the moon was not only icy, but had a young, frequently rejuvenated outer surface. Scientists believe that this ocean exists because of tidal heating in Europa’s interior, caused by orbital dynamics between it and the other large moons of Jupiter.

Prime conditions for life

An interview with Geronimo Villanueva of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, lead author on one of the two current papers, highlighted his ideas on the importance of the discovery.

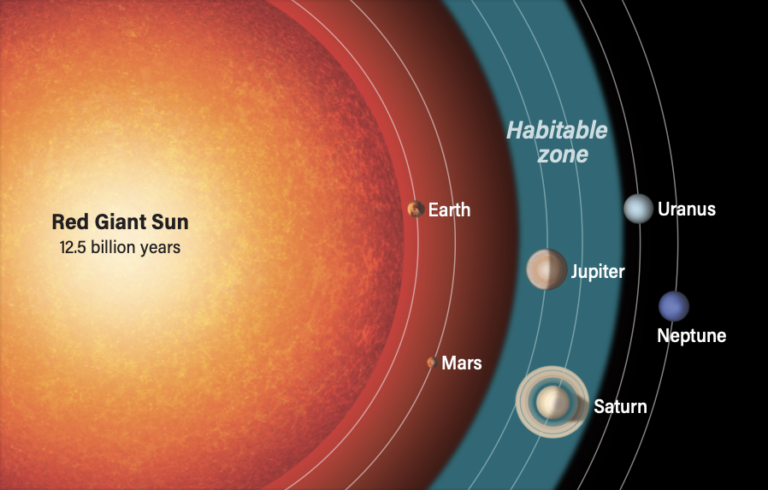

“Within the solar system, there are not many places which are habitable for life as we know it,” says Villanueva. “We have our own planet. We have Mars in some conditions below the surface. And then we have these icy moons, Europa and Enceladus, a small moon of Saturn with many similarities to Europa.” Villanueva continues: “So within that when we’re thinking about habitability and conditions for life, Europa is prime in our solar system because we think that below that crust of ice are big bodies of water. And the body of water has been estimated to be even larger than we think it is on our planet.”

The likely existence of the subsurface oceans of Europa and Enceladus for as long as several billion years supports the notion that they may be good places to seek evidence of past or present life. But to find any such evidence, scientists would have to send probes capable of boring through crusts of ice believed to be kilometers thick. Crucially, however, the discovery of CO2 at Tara Regio shows that some of that subsurface ocean may come to the surface, ready to be more easily discovered.

How and where CO2 was found on Europa

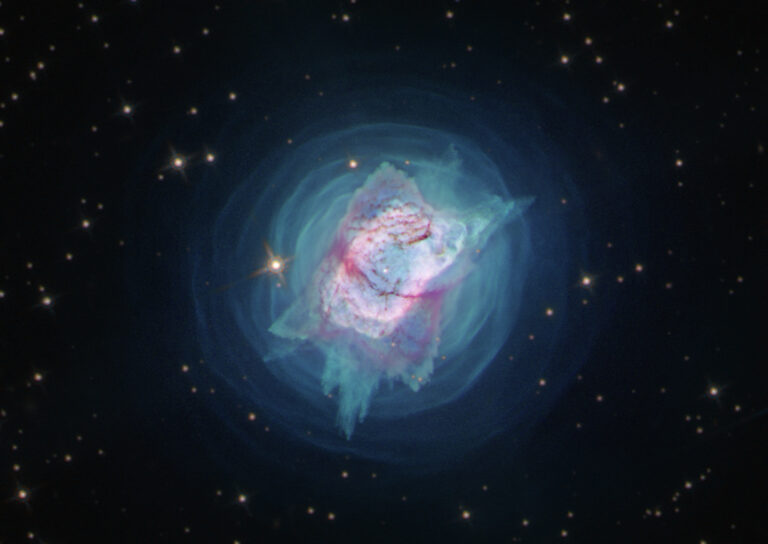

The Webb Space Telescope has opened a door to new, powerful discoveries. “The beautiful thing about JWST is that it allows us to map the presence of CO2,” says Villanueva. “And when we mapped it, we could tell that it was not simple CO2, it was complex CO2.”

This type is more likely to be present in places that could be friendly to life, suggests Villanueva. “On Earth, life likes chemical diversity. The more diversity, the better. We’re carbon-based life. Understanding the chemistry of Europa’s ocean will help us determine whether it’s hostile to life as we know it, or if it might be a good place for life.”

And there’s even more to the discovery, says Villanueva. “[The carbon dioxide] was localized in one area. One of the big questions when you find CO2 is where it’s coming from. If it’s coming from micrometeorites or things from outside the moon, you tend to think everywhere will be more or less the same, but in this case it was localized in a specific area. This [area] is known to be very geologically new chaos terrain, which is very interesting because it indicates something is happening there.”

Again, the inference is that complex carbon dioxide rising up from the subsurface ocean in this area would suggest it’s a good place for potential life.

As a result of this discovery, earthbound scientists also have a better basis for studies to be conducted by upcoming missions to the icy moons of Jupiter. These include NASA’s Europa Clipper, due to be launched in October 2024, and the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) produced by the European Space Agency (ESA) that was launched in April 2023. When these missions arrive, observatories like JWST will help guide their detailed investigations of Europa and the other large icy moons for evidence of life.

According to Villanueva, the CO2 find was made during a proof-of-concept scan, during which JWST targeted Europa to illustrate the kinds of data it is capable of collecting when pointed at worlds both near and far. “Making these initial measurements allows people to come up with even better ideas to use the instruments to go deeper, to maximize the science return,” says Villanueva. “And the good thing about it is that this is open to the community. Anybody can go and apply to use the telescope if they have a good pitch.” Science at Europa, and with JWST in general, may only just be getting started.