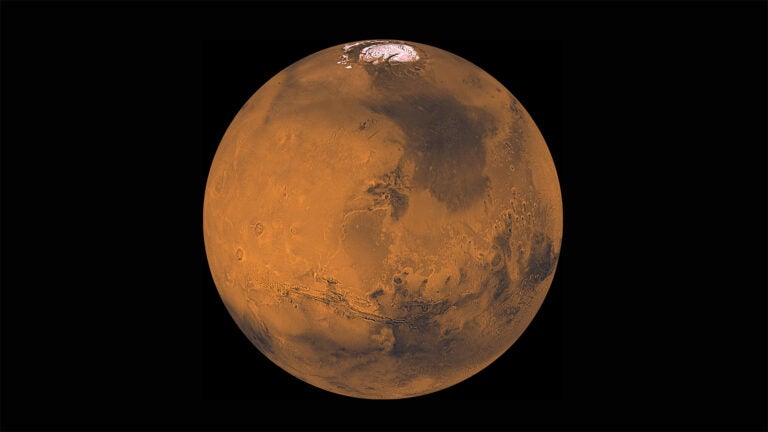

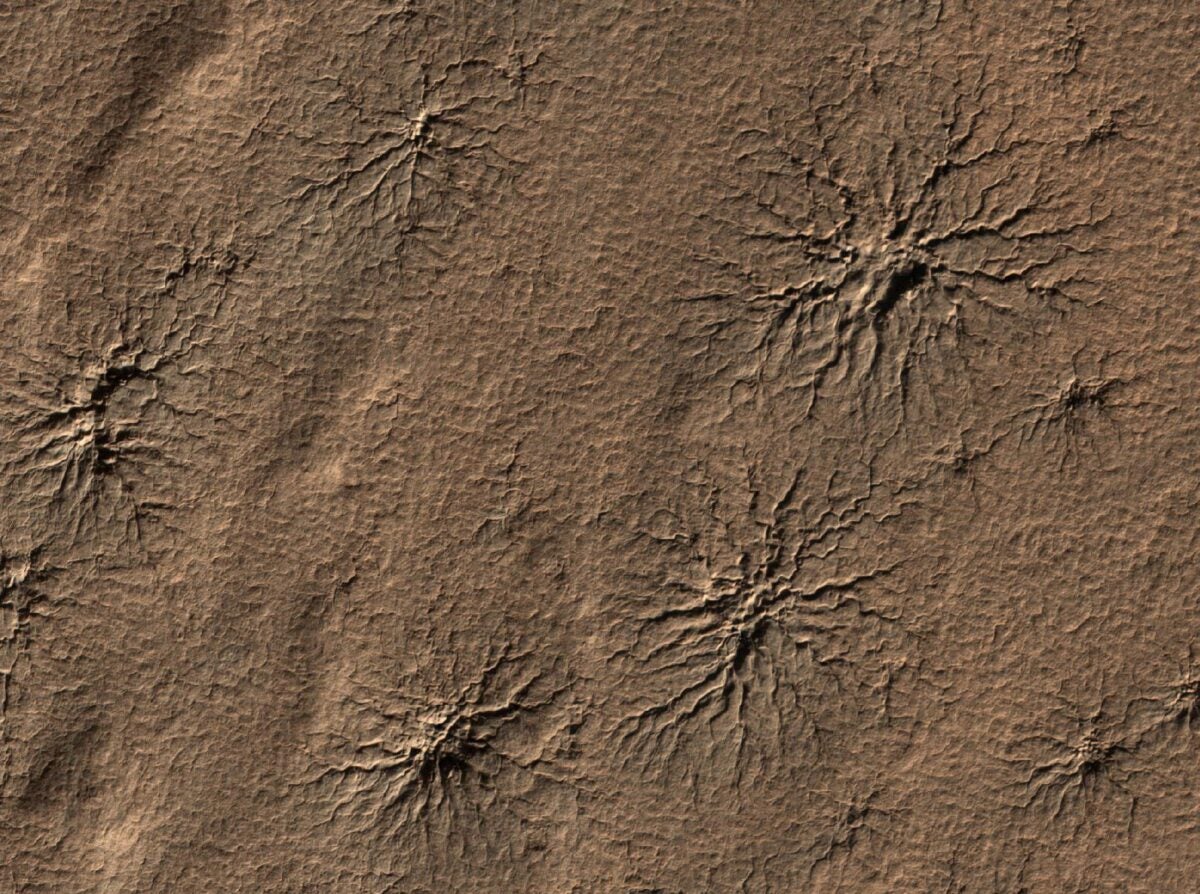

Each spring, when the winter frost departs, the bulbous bodies and sprawling legs of “spiders” appear across Mars’ southern hemisphere. They’re known as araneiform terrain, and scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, recently recreated the formations in a vacuum on Earth to better understand how they form and what they can tell us about the martian climate.

Related: The science behind the ‘spiders’ on Mars and the Inca City

Forming araneiform terrain

Since researchers discovered araneiform terrain in 2003 using NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor orbiter, they have believed that the terrain — along with similar patterns, knowns as halos, fried eggs, or lace — form via a process called the Kieffer model.

Each winter, carbon dioxide condenses out of the atmosphere onto the martian regolith, forming slabs of translucent ice. The Kieffer model says that solar radiation can pass through the ice and heat the rocky ground underneath, which in turn releases infrared radiation in a kind of greenhouse effect, heating the ice from the bottom up and causing it to sublimate (turning directly to a gas, like dry ice). This causes a buildup of pressure until the slab explodes open, forming cracks as the gas expands and escapes. Plumes of dust and debris erupt outward during this process, littering the surrounding area. The ground grows scarred from these interactions, leaving troughs in patterns like the spiders.

Making Mars in the lab

Despite their confidence in this theory, scientists have been unable to prove it until now. A new study, published Sep. 11 in the Planetary Science Journal, tested whether the Kieffer model was the cause for these springtime changes. Within a barrel-sized chamber called the Dirty Under-vacuum Simulation Testbed for Icy Environments (DUSTIE), a team at JPL was able to drop the temperature to minus 301 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 185 degrees Celsius) at very low air pressure to mimic the martian atmosphere for the experiment.

The study’s lead author, Lauren Mc Keown, and her team put 0.8 inch (2 centimeters) of simulated martian regolith into DUSTIE and then pumped in chilled carbon dioxide, which formed a thick, translucent sheet of ice over the mock dirt.

After the ice formed, they warmed the dirt with a heater from beneath, experimenting with varying heat levels and placements. Different scenarios formed different patterns similar to the various halos, pits and spider shapes left on Mars each year. In many instances, a plume erupted from the dirt, lasting as long as 10 minutes in one case.

“It was late on a Friday evening and the lab manager burst in after hearing me shrieking,” Mc Keown, who had been working to make a plume like this for five years, said in a NASA news release.

The fact that researchers were able to recreate the spiders in the lab and watch them form according to the Kieffer model is important for understanding Mars’ climate, both today and in the past. Mc Keown plans to continue this experiment using simulated sunlight as opposed to a heater in order to more accurately recreate conditions on the Red Planet.

Despite confirming how they form, there are still many open question about Mars’ spiders. Why do they only form in some areas? And do new spiders form every year, or are the structures we see simply the scars left from when conditions on Mars were right for making them, uncovered each time the frost disappears in spring? The answers to these questions will help researchers unlock priceless information about martian weather and climate.