Solar scientists have a problem: They haven’t been able to fully explain why the Sun’s atmosphere is about 100 times hotter than its surface.

Now, observations of a solar wave rising up from a sunspot may help explain at least one of the ways in which the atmosphere, called the corona, gets so hot.

Why should the Sun’s atmosphere be hotter than the region below it? If you think about it, this makes no sense.

Nuclear fusion in the center of the Sun heats this region to an astounding 27 million degrees F. Each successive layer of the sun is cooler than the one below it. In fact, the Sun’s surface is a relatively brisk 10,800 degrees F.

If you’ve ever sat next to a campfire and had to move away a bit because it was too hot, this should make perfect sense.

Scientists call this the “coronal heating problem,” and they’ve been trying to solve it since the 1930s.

Today, there are two main theories. One holds that loops of the Sun’s magnetic field induce electric currents in the corona. These release energy and cause heating.

The other theory posits that waves carry energy from the Sun’s interior up into the corona. The new research illuminates how this can occur.

Violent turbulence inside the Sun produces sound waves. These so-called “helioseismic waves” surge from the interior, reflecting off of the underside of Sun’s surface and bouncing back down. But they are then bent back upward by a physical process known as refraction, returning to the surface.

In this way, the helioseismic waves are trapped — and they actually cause the Sun to vibrate in millions of different patterns, or modes.

But is there a connection between the helioseismic waves that roil the Sun’s surface and the corona above it? The new research suggests that the answer is yes.

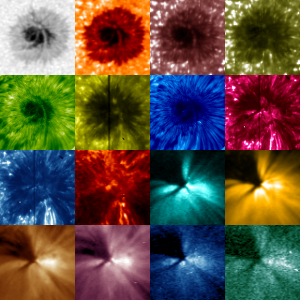

As part of their study, published Oct. 11, 2016, in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the researchers used data from two NASA spacecraft — the Solar Dynamics Observatory and the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph — plus the Big Bear Solar Observatory in California. Rapid-fire images of the sun from these observatories, acquired in 16 different wavelengths, allowed the scientists to track a wave traveling up through the surface and into the lowest reaches of Sun’s atmosphere.

“We see certain kinds of solar seismic waves channeling upwards into the lower atmosphere, called the chromosphere, and from there, into the corona,” says Junwei Zhao, a solar scientist at Stanford University in Stanford, California, and lead author on the study.

This channeling of a solar wave “may bring substantial energy up into the higher atmosphere, where the oscillatory energy gets dissipated and contributes to the coronal heating,” Zhao and his colleagues wrote in their paper.

The new findings point toward further research that could eventually fully solve the deep and abiding mystery of the coronal heating problem.

This originally appeared on Discover.