Update: Pieces of the asteroid have been found! Here’s a post from the Natural History Museum in Berlin, which includes this photo of the happy searchers with a fragment of the asteroid.

The SETI Institute has more on the recovery here.

Here’s our original article:

Germans out and about around 1:30 local time on the morning of Jan. 21, 2024, were in a perfect spot to see an unusual — but not unexpected — phenomenon.

A tiny asteroid about a yard (1 meter) in size, dubbed 2024 BX1, streaked across the dark sky in eastern Germany before disintegrating. Here’s what it looked like from a camera in Leipzig:

The asteroid was first detected by Krisztián Sárneczky, a researcher with the Konkoly Observatory in Budapest. NASA later confirmed the asteroid’s path over Berlin in a post on social media. While the object was no threat to the planet, it was an opportunity to test asteroid-spotting capabilities on Earth in case something more catastrophic is ever on the way.

“Objects this small can reach the Earth once a year. That’s normal, and as telescopes and their capabilities get better, we’re bound to discover more and more,” says NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Davide Farnocchia, an engineer who works on calculating the orbits of asteroids and comets.

Flying toward Earth

Sárneczky spotted 2024 BX1 with the observatory’s Schmidt telescope on Jan. 20 at 10:50 P.M. Hungarian time. It was identified as an asteroid because it was moving relative to the more distant, stationary stars. Sárneczky reported the sighting to the International Astronomical Union Minor Planet Center (MPC) which sent a notification to NASA’s impact hazard assessment system, Scout. When Scout determined that 2024 BX1 would hit Earth, it sent a message to Farnocchia and other scientists who track near-Earth objects (NEOs). A few hours later, the asteroid flashed through the sky, burning up.

“I started getting text messages and I went back to my computer just to see, but essentially, the whole thing worked flawlessly in an automatic fashion and new impact predictions came in, and they got better and better as new data was reported,” says Farnocchia.

With Scout, NASA can automatically detect an object’s orbit and alert researchers if something is about to hit Earth. Scout also picks up artificial items like satellites or space junk. Farnoccahia says the system even alerted him about the interstellar object ‘Oumuamua — although of course in this case, Scout did not predict an impact. Instead, it alerted them because it could not find an orbit that fit ‘Oumuamua.

No cause for alarm

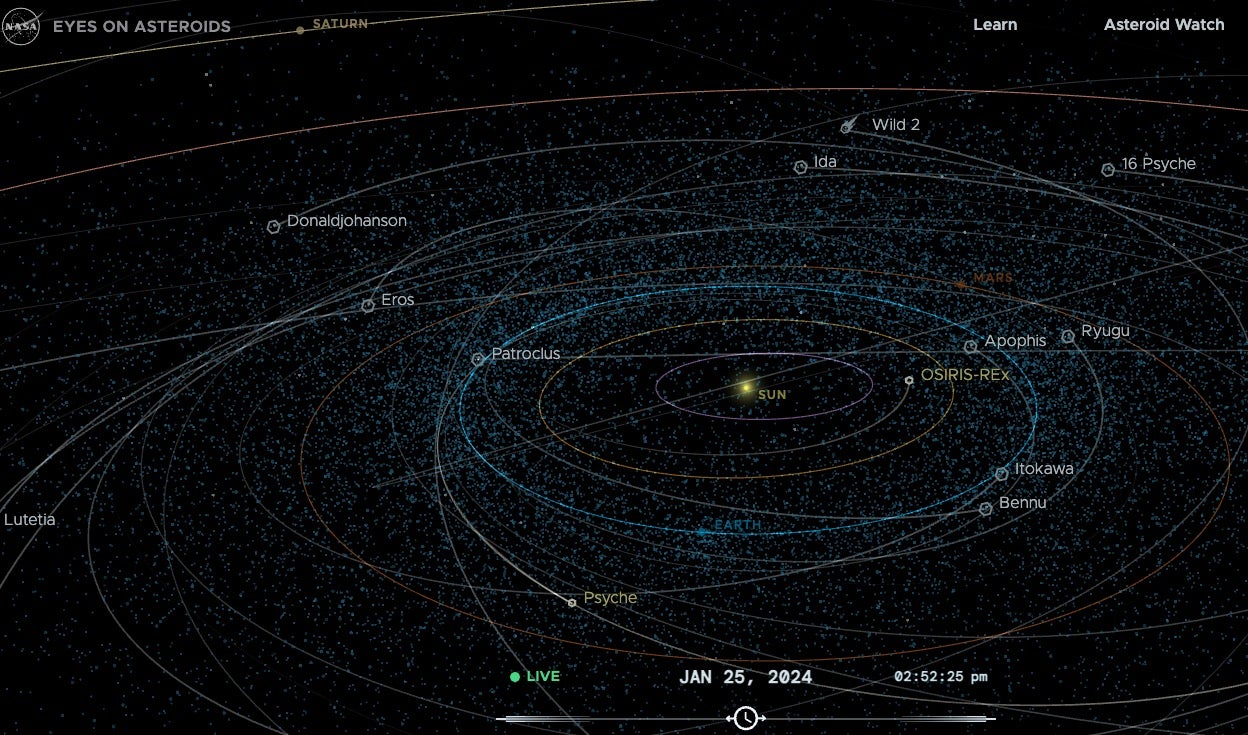

Sárneczky has detected asteroids like 2024 BX1 before. In 2022, he observed a small asteroid named 2022 EB5 two hours before it burned up over the Norwegian Sea. Sárneczky has also discovered hundreds of minor planets in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, including numerous near-Earth objects (NEOs). NEOs are typically defined as any object whose orbit comes within 27.9 million miles (44.9 million kilometers) of Earth’s. In total, we know of about 34,000 NEOs.

Small asteroids like 2022 EB5 and 2024 BX1 enter Earth’s atmosphere about every 10 months, said Paul Chodas, director of JPL’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies, in a 2022 statement. Still, only eight have ever been observed prior to impact because they are hard to see until the last few hours before they hit. Survey telescopes must happen to be observing the right patch of sky at the right time to catch them in action.

Larger and potentially dangerous asteroids are detectable at much farther distances, and experts would know well in advance if one were heading for Earth. Still, scientists want to track any asteroid to test response times and prediction rates of models.

“We had less than three hours in this case to figure out what was going to happen from first detection to when [2024 BX1] entered the atmosphere. And within three hours, we were able to collect enough data, pinpoint the impact locations within 100 meters [330 feet] or so,” says Farnocchia.

Detecting the big ones

Experts are looking for those larger, potentially dangerous asteroids — those larger than 460 feet (140 m) — that come close to Earth. These asteroids are of a size on what Farnocchia says is a threshold for causing regional-scale devastation. While an impactor of this size won’t wipe out Earth, it can cause damage regionally. For an object to cause global-level damage, it must be at least 0.6 mile (1 km) in size.

Asteroids about the size of a tennis court (66 feet [20 m]) hit Earth every 50 to 100 years, per the European Space Agency (ESA). They can inflict a lot of damage. Both NASA and ESA have projects underway that will work to detect both harmless and Earth-shattering asteroids. Like the stars in a daytime sky, many asteroids are hidden by the Sun’s glare. Some of these asteroids could make their way toward Earth without anyone knowing.

ESA’s Near-Earth Object Mission in the Infrared (NEOMIR) mission, still in development, will serve as an early detection system that will orbit between the Sun and Earth at the L1 Lagrange point. NEOMIR’s infrared detector is designed to pick up asteroids heading our planet from the direction of the Sun, where optical telescopes can’t see them. Instead, NEOMIR will detect heat from the asteroid itself, identifying potential hazards at least three weeks before impact.

NASA’s successful Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) has showed we can move an asteroid with a spacecraft. DART smashed into Dimorphos, the tiny moon circling the larger asteroid Didymos, on Sept. 26, 2022. The impact changed Dimorphos’ period around its parent by 32 minutes.

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory

Detecting smaller asteroids such as 2024 BX1 may also become more common as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory comes online next year. The observatory will scan the entire Southern Hemisphere sky every few days for changes like streaking asteroids or the flashes of supernovae. And planetary scientists are particularly excited about its ability to detect potentially hazardous asteroids, whose paths may come close to or even cross Earth’s orbit in the future.