This summer, University of Florida (UF) astronomers inaugurated the world’s largest optical telescope on a nearly 8,000-foot mountaintop.

But it was a far more modest observatory, located just above sea level in rural Levy County and just down the road from the UF campus that proved key to a new discovery about what one astronomer termed “one of the weirdest” planets outside our solar system.

Three UF astronomers are among the authors of a paper pinning down the extravagant orbit of HD 80606b, a Jupiter-sized planet nearly 200 light years away. The team made observations of the planet eclipsing its star from a 41-year-old telescope at the department’s Rosemary Hill Observatory in Bronson 30 miles (48 kilometers) west of Gainesville.

The Rosemary Hill Observatory was founded in 1967 on an 80-acre site in Levy County less than 140 feet above sea level. It has two telescopes, the larger of which is a 30-inch Tinsley reflecting telescope. Although faculty members and graduate students have used that telescope and its 18-inch companion for research, they serve mainly as teaching tools. For research, astronomers often travel to remote mountaintops where larger, more sophisticated telescopes can capture light from far more distant stars at much finer resolutions — now including the largest of them all, the 34.1-foot Gran Telescopio Canarias, perched at 7,874 feet above sea level on a mountaintop in Spain’s Canary Islands.

The events of the night of June 4, 2009, however, proved that small, simple telescopes can still play starring roles.

On that night, Reyes and Colon joined teams at about a dozen different observatories spread from Massachusetts to Hawaii to observe the planet eclipse its host star, HD 80606.

Astronomers noticed the eclipse for the first time in late February, but they only managed to observe the end of it. The planet completes one orbit around its star every 111 days, so the next chance for observation came June 4. The eclipse lasted nearly 12 hours, yet any single observatory can only observe it for a short time between twilight and when the planet and star disappear below Earth’s horizon. As a result, 25 astronomers worked together, relay-race fashion east to west, to capture the event.

Colon, Reyes, and Eric Ford, UF astronomy assistant professor, spent several days testing and readying the Rosemary Hill telescope. However, the weather had been poor for weeks, and prospects didn’t look good. On the appointed night, it was too cloudy at the first observatory, in Massachusetts, for successful observations. The Florida observatory was next.

Colon said that despite widespread clouds, she and Reyes located a reference star and zeroed in on HD 80606 just in time for the beginning of the eclipse. The team caught only part of the event, but the next observatory, in Indiana, was able to pick up soon after. All told, six observatories gathered about six hours of observations, capturing more than half of the eclipse. Although most were small, they included the 31-foot Keck I telescope in Hawaii. Ford participated remotely in those observations from Berkeley, California.

When Colon uses the Gran Telescopio Canarias, she submits her requirements for observation, then awaits the results from astronomers at the telescope. The Rosemary Hill observations were completely different.

“You are staring at a star as a planet crosses in front of it, which is pretty amazing,” she said. “It’s definitely a unique experience that you can’t get from the remote observing that I do.”

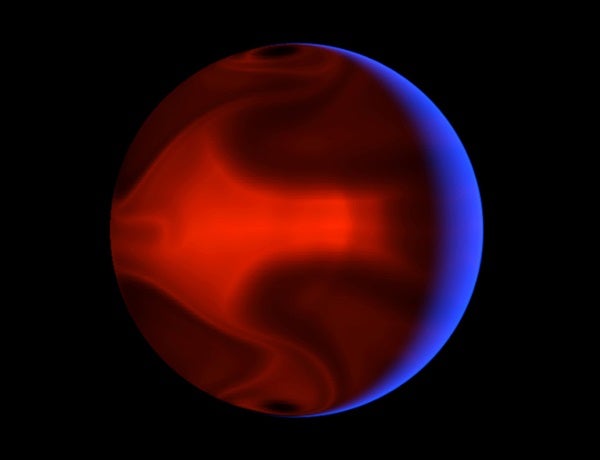

Most planets orbit their stars in a more or less circular shape. But HD 80806b’s orbit is an elongated ellipse, as though someone had grabbed its orbit and squeezed. Astronomers were unsure of the cause of this comet-like orbit, but the leading theory was a companion star’s gravitational pull. By combining their observations of the eclipse, the team demonstrated the planet’s orbit is not aligned with the star’s rotation, which suggests this theory is probably correct, Winn said.