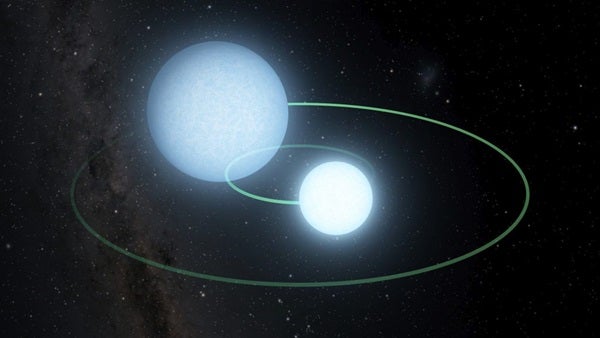

But in the extreme world of binary white dwarfs, this new discovery, called ZTF J1539+5027, is an extreme case. The two tiny stars orbit each other every 6.91 minutes, within a space smaller than the planet Saturn. Researchers led by graduate student Kevin Burdge from the California Institute of Technology published their findings in the journal Nature on Wednesday. They first spotted the fast-changing system using the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory, before following up with the Kitt Peak 2.1-meter telescope in Arizona. The team points out that the system will be a perfect target for the upcoming LISA gravitational wave detector, set to launch in 2034.

Fast Pair

In their younger days, these stars probably orbited much farther apart. But identical twin stars are rare, and one usually starts off at least a little bigger than the other. This bigger star then races through its life a little quicker. That means that one star reaches its large and puffy phase while the other is still star-like, and they can end up sharing – or stealing – material from each other. In many cases, this trade-off forces the pair to spiral closer together.

In this newly-found system, one of the stars is currently slightly larger than Earth but weighs about 60 percent the mass of our Sun. The other dwarf is puffier and a little larger in diameter but weighs only one-third of its companion. Already quite close, the two stars grow 10 inches closer per day, thanks to the energy they radiate away as gravitational waves.

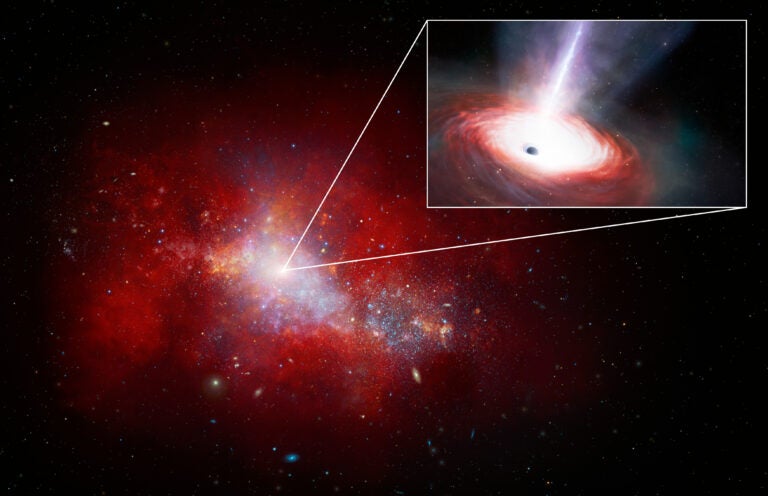

Such systems with clear gravitational wave emissions are expected to be common in the universe, but only a few have been positively identified so far. That may change when LISA, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, launches in the 2030s. Like LIGO, which found colliding black holes in 2015, the instrument will hunt for the invisible ripples in space-time caused by gravitational waves. But LISA will hunt smaller prey, like these binary systems. And unlike many of LIGO’s sources, which can only be observed through gravitational waves, binary pairs like J1539 may yield extra information, appearing both through gravitational waves and visible light.

While LISA isn’t ready for launch yet, scientists are excited to have a prime observing target already picked out, and know that LISA’s prey is out there, waiting to be observed.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Zwicky Transient Facility was located at Kitt Peak.