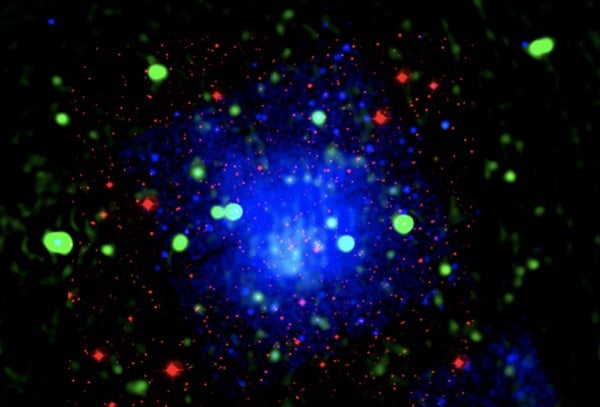

Sarthak Dasadia discovered the strong shock in the merging galaxy cluster Abell 655 using observations from the Chandra X-ray Observatory. The shock to the north of this cluster is second in strength only to the Bullet Cluster shock.

The shock travels at an astonishing speed of 1,700 miles (2,700 kilometers) per second, about three times the local speed of sound in the cluster. By comparison, NASA’s Juno spacecraft in 2013 became the fastest man-made object when it was slingshot around Earth toward Jupiter at a relatively slow 25 miles (40km) a second.

“Studying mergers of galaxy clusters has proven to be crucial to our understanding of how such large scale objects form and evolve,” said Dasadia. Shocks provide unique opportunities to study high-energy phenomena in the intra-cluster medium — the hot plasma between galaxies. “This could open a door where people can do a number of different studies based on what I have found.”

Already, scientists are targeting shocks in galaxy clusters to study dark matter, the magnetic field in the intracluster space, particle acceleration, and energy transfer in the intracluster medium.

The universe is populated with galaxy clusters that are relaxed and unrelaxed, Dasadia said. The relaxed ones are mellow — they’ve been around a lot longer, have seen lots of past mergers, and really aren’t dynamically active. It’s the unrelaxed clusters like Abell 665 that are good candidates to study merger features such as shocks and turbulence.

“These galaxy clusters are not boundary objects,” he said. “They do not have a very well-defined boundary around them.”

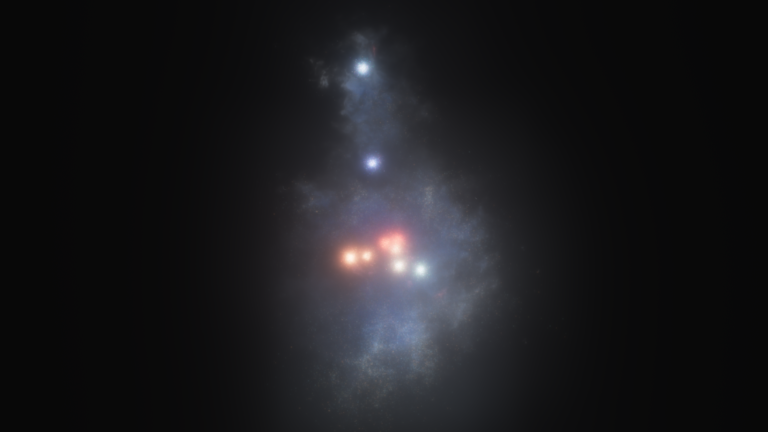

When the undefined boundaries of massive clusters of galaxies 3 million light-years across are drawn together in a slow-motion collision, their cold cores and surrounding hot gases are disrupted into shock waves and gas fronts of various temperatures.

“When two cold cores collide, they may create a shock of heated gas,” Dasadia said. “Such mergers are actually among the most energetic events in the universe, other than the Big Bang itself.”

If talking about fronts and shock waves and temperature differentials sounds lot like the weather on Earth, Dasadia said that’s because there is not much difference as far as the physics involved.

“Technically, we observe the same features in space that we do on Earth,” he said. “This area has been studied extensively before at small scales, but few had done the work to discover what I found here at such big scales.”

He was able to measure the velocity of the collision and the dynamics of what is happening in it — or rather, what was happening in it. It took 3.2 billion years for the light in the observations to reach Earth, so the events all happened that far back in time. Dynamic observations included the energy in the collision, the gas movement, and measurements of the discrepancy between the visible and dark matter involved.

“It amazes me how long it takes for this information to even reach the Earth,” Dasadia said. “Then I am also amazed by our technology, by how much we have advanced in developing the telescopes and equipment it takes to be able to observe and study these interactions.”