Going back somewhat farther — to a period lasting from 540 to 500 million years ago — the fossils of trilobites also offer unambiguous evidence for life. With many trilobites fossilized in fine-grain shales, biologists can inspect clearly recorded details of their anatomy and make educated guesses about their physiology.

Stepping back once more, to an era from 575 to 543 million years ago, the odd creatures of the Ediacaran period come to light. While paleontologists aren’t sure how these marine organisms lived and functioned, there’s no doubt they were alive.

But what about life’s earliest traces?

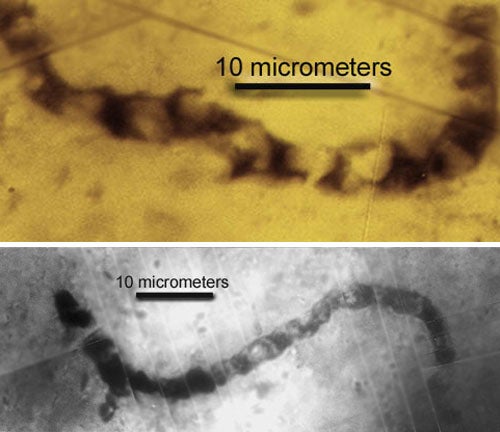

The oldest surviving fossils are microscopic. Those shown here — the oldest in the world — are of microscopic bacteria. They are preserved in fragments of older rocks in a formation geologists call the Apex chert. This formation belongs to the Pilbara group of northwestern Australia and has been dated to 3.465 billion years ago. As the microfossils lie contained within the chert, they are actually older than the chert itself, although by how much is unclear.

These Apex organisms, found in 11 different types, may include cyanobacteria, or photosynthesizing blue-green algae. But whether or not the Apex bacteria were capable of photosynthesis, scientists know that cyanobacteria only slightly younger formed layered mats, called stromatolites, in shallow ocean water. Stromatolites resemble a pancake stack, with the bacterial layers interleaved with deposits of sand or carbonate rock.

Stromatolites still exist, being found most commonly in Australia going about their ancient business. Billions of years ago, as now, the metabolism of cyanobacteria takes in Earth’s atmosphere — rich in carbon dioxide in the early days — and excretes oxygen as a waste product. Ages ago, this process slowly altered the atmosphere’s chemical makeup.

William Schopf of UCLA led the team that discovered the fossils. As he writes in the book Life’s Origin, “The Apex fossils are scrappy, hard to find, and difficult to study. They are abundant, but they are also mangled, shredded, and charred.” The latter is the result, he notes, of the fossil layer being caught between two lava flows whose dates pinned down the age of the chert. About the fossils, he says, “Given their immense age — and their fragile makeup and their minute size — it’s remarkable that they have survived at all.”

While an age of 3.465 billion years makes the Apex formation incredibly old by human standards, Earth had existed for a billion years when those fossils became embedded in the chert. It’s reasonable to wonder how much earlier life emerged.

Going back farther requires finding still-older rocks, and that’s not easy. Earth’s oldest rocks lie in three locations: northwestern Australia, eastern South Africa and Swaziland, and southwestern Greenland. (If older rocks exist at Earth’s surface, geologists have yet to find them.) Of the three places, the oldest rocks belong to the Isua group of southwestern Greenland. They are 3.85 billion years old. The Isua rocks date from the end of the lunar cataclysm, when large impacts struck the Moon — and presumably Earth as well. Because this heavy bombardment was extremely violent, it’s possible that no older rocks survive intact.

Unfortunately, the Isua rocks preserve no fossils. While some of them were originally sedimentary — the kind that can preserve fossils — they have been greatly squeezed and heated in a process called metamorphism. No fossils could have survived that treatment and remained recognizable. However, when geologists examined carbon isotopes in the rocks, they found crystals of graphite enriched in carbon-12. This geochemical anomaly is the best surviving evidence, however circumstantial, for the earliest traces of life.

“I don’t know how far back in time the fossil record will eventually be traced,” Schopf writes in his book Cradle of Life. “Yet because the search has hardly begun, it seems likely that fossils older than the Apex filaments will turn up, perhaps in the Western Australian Pilbara, still the most promising region known. But I am doubtful that the rock record will ever yield evidence of the origin of life itself. The very first forms of life can hardly be expected to have built stromatolites or carried out complicated biochemical processes of the type that leaves an isotopic signature.”

Even if older rocks than the Apex cherts never turn up, we can still say that life emerged on Earth about as soon as conditions allowed. This suggests that life could be common in the universe — and that’s a strong hint to keep looking.