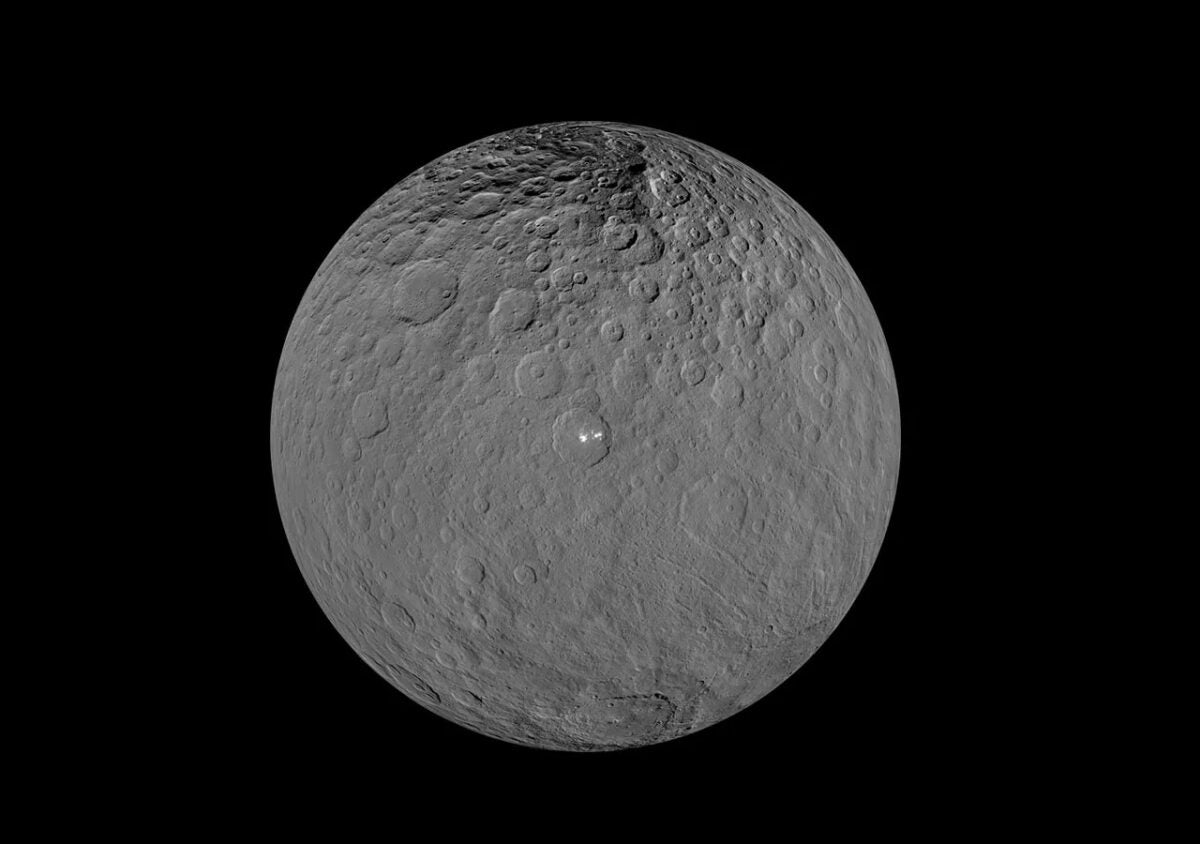

Dwarf planet Ceres is one of the most enigmatic worlds in our solar system — one whose secrets scientists have only been uncovering in the last decade. When NASA’s Dawn mission arrived in 2015, it uncovered an active, salt-rich world that might have — or once have had — an ocean. Now, new research provides evidence that it might also hold the right stuff for life.

In a paper published Wednesday in Science Advances, researchers present evidence that a series of chemicals called long-chain aliphatic organics (AOs) — basically long chains of hydrocarbons that often form natural lipids (fats) — may have formed within Ceres and come to the surface via cryovolcanism.

Related: Explore Ceres’ icy secrets

An evolving world

Prior to this study, scientists knew there were AOs on Ceres, but whether they had been deposited onto the surface by meteorites or present already was unclear. The latter idea bolsters the case that Ceres was once an oceanic world, as similar compounds are found on other water worlds like Enceladus. The relative abundance of these chemicals on Ceres was also too high to have come from meteorites alone.

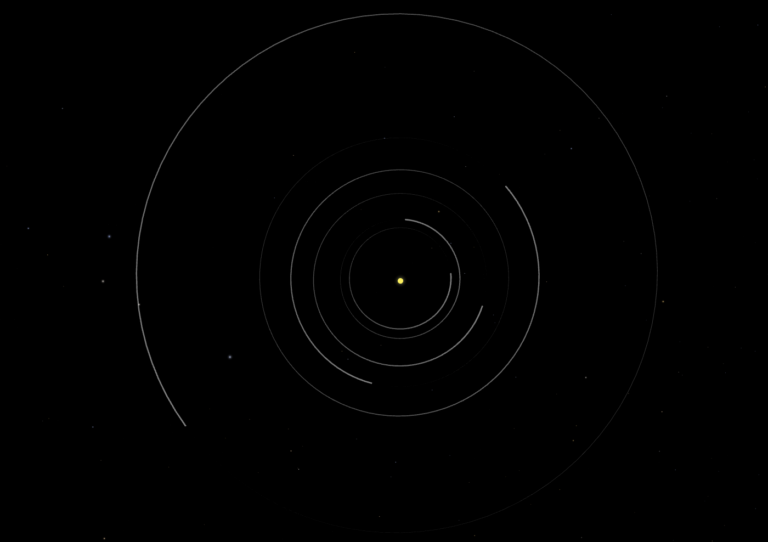

Ceres is the largest object in the main belt. And it doesn’t look much like other objects there; scientists think it may have formed farther out in the solar system, closer to the Kuiper Belt, where other dwarf planets like Pluto and Eris reside. It may have once hosted an ocean that lasted for hundreds of millions of years, and now may exist only in localized pockets under reservoirs of slushy brines nearer the surface.

AOs degrade quickly, within about 10 million years. That means the AOs seen on Ceres’ surface must have formed recently. Additionally, the AOs are found near sites that have other evidence of plumelike activity.

“Ceres is a geologically active world. We have identified very recent (in geological time) mountains, domes and fractures,” says lead author Maria Cristina De Sanctis, a planetary scientist at INAF-Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali in Italy. “The presence of AOs that should be recent, otherwise not observable, confirms that Ceres can be considered a still evolving body.”

Creating a mini-Ceres

To determine why they were seeing such high concentrations of AOs, the team took Dawn data and compared it against a recreation of Ceres-like conditions in a lab. This mini-Ceres was given AOs and then subjected to the various kinds of radiation you’d expect in interplanetary space near its orbit around the Sun. The team tracked the breakdown of the AOs to estimate when the currently observed AOs may have made it to the surface, as well as determining their origin. Based on their results, the team believes AOs buried beneath the surface were exposed over time, strengthening the case that they came from the deep ocean of Ceres, rather than meteorites from above.

The results also showed that the current abundance is probably the result of even higher abundances of AOs being pushed up to the surface, with some breaking down before more was pushed up.

And, if Ceres had an ocean, that ocean might have once supported life. De Sanctis says that the presence of clays, carbonates, briny water, ice, salt, and organics all point to the main-belt world having the right chemicals. And the AOs help bolster the case.

“In particular, the high quantity of AO and the kind of AO (spectrally similar to terrestrial kerogens [which contain detritus from dead organisms]) increase the potential of Ceres in terms of habitability,” she says.

Our understanding of the many ocean worlds in our solar system is just beginning. Although researchers are still combing through the wealth of data from the now-ended Dawn mission, the new mysteries they’ve uncovered at such a nearby world might mean it could soon be due for another, closer look.