Without starlight to see them directly, the team, which includes Regina Jorgenson of the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii in Manoa, observed the young galaxies’ outskirts in silhouette.

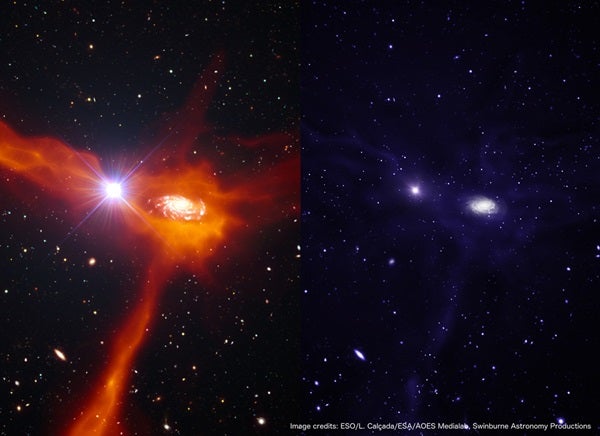

They searched for telltale signs of hydrogen molecules absorbing the light from background objects called quasars — supermassive black holes sucking in surrounding material — that glow very brightly.

“Previous experiments led us to expect molecules in about 10 of the 90 young galaxies we observed, but we found just one case,” said Michael Murphy from Swinburne University of Technology in Australia.

Astronomers believe that stars begin to form in cold gas that is rich in molecules. The team observed galaxies at a time when the universe was most actively forming stars, about 12 billion years ago.

“This is a little mystery,” Murphy said. “This is when most stars are born, and we think this gas forms stars eventually, but it lacks the key ingredient — molecules — to do so.”

The team believes that location and time are the key.

“The gas we observe in silhouette probably lies too far from the galaxies to form stars,” Jorgenson said. “It’s got lots of potential, but it hasn’t had time to fall into the richer, denser parts of the galaxies, which might be better stellar nurseries.”

The researchers made new observations of more than 50 quasars for this study using the 6.5-meter Magellan telescopes in Chile.