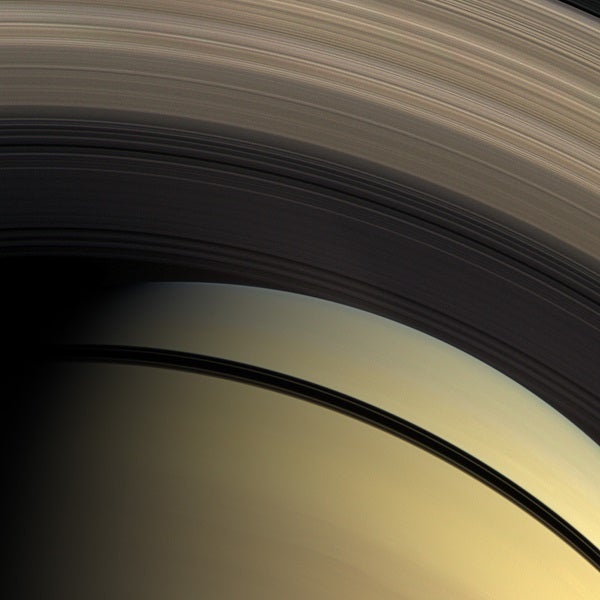

From the propeller-shaped disturbances and embedded moonlets in the A ring inward to the nearly transparent D ring and outward to the bright arc circling the faint G ring, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has given astronomers a new look at the complex system of rings circling Saturn.

Six years into the mission, rings researchers took a step back and reviewed some of its most important findings — and noted a few of the many mysteries that remain — in a paper featured on the cover of the March 18 issue of the journal Science.

The paper is led by Jeffrey Cuzzi of NASA’s Ames Research Center and Joseph A. Burns, Cornell professor of astronomy and the Irving Porter Church Professor of Engineering; its co-authors include Cornell postdoctoral researchers Matthew Tiscareno and Matthew Hedman, and Philip Nicholson, professor of astronomy.

On a broad level, the authors write, the mission has revealed a ring system that is far more dynamic and varied than many expected.

“According to theory, astronomical discs should be uniform and smooth, with everything moving serenely along, but our observations have shown that life isn’t as simple as that,” said Burns.

Instead, the researchers see particles ranging in size from a few centimeters to many meters in radius. And, according to studies by Hedman and Nicholson, two competing forces — gravitational attraction that tries to clump ring particles together and tidal forces that pull them apart — cause particles in the A and B rings (the two main rings) to form self-gravity wakes, or elongated clumps, as they orbit the planet.

Saturn’s moons, meanwhile, exert their own influences on the ring particles, causing a scalloped pattern that rotates with the moon and ripples away, with individual particles moving in and out of the ripple, like water molecules moving in and out of a wave in the ocean. These ripples, so-called spiral density waves, push the moons that caused them outward, away from the rings.

In 2006, a team led by Tiscareno reported propeller-shaped disturbances in the A ring, a discovery that indicates the presence of smaller moonlets (10 meters to 1 kilometer in radius) that are too small for Cassini to see directly but large enough to exert gravitational force on the particles around them. By observing the propellers over time, the researchers hope to learn more about similar processes that are thought to occur in the early stages of planet formation.

The Science paper covers only an outline of Cassini’s discoveries so far. At least one textbook has been written on the mission, and much more data remain to be analyzed.

Still, plenty of questions remain unanswered. The rings are known to be 95 percent water ice, but the composition of the other 5 percent, which lends the rings a reddish tint, is still a mystery. Researchers hope to learn more about early planet formation by watching the highly dynamic F ring. The B ring, the densest in the system, is not well understood. And the age and origin of the rings are still a matter of debate.

In that vein, the paper is just a mid-mission survey of Cassini’s accomplishments to date, said Burns. If the spacecraft stays healthy until the mission’s expected 2017 end date, it will provide a new view of the region that NASA’s Voyager spacecraft observed 30 years ago.

“We basically understand the A ring … but we’re only at the beginning of the alphabet,” Burns said. “We don’t understand the B ring for sure, and we don’t understand most of the structure in the C ring. So we have our work cut out for us. Fortunately we’ve got a spacecraft which is operating quite well — its capabilities are almost undiminished.”