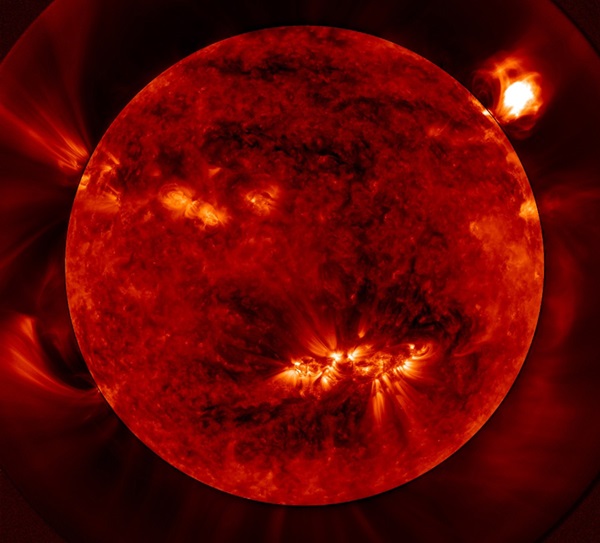

Now, an instrument on board NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), developed by Smithsonian scientists, is giving unprecedented views of the innermost corona 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

“We can follow the corona all the way down to the Sun’s surface,” said Leon Golub from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Previously, solar astronomers could only observe the corona by physically blocking the solar disk with a coronagraph, much like holding your hand in front of your face while driving into the setting Sun. However, a coronagraph also blocks the area immediately surrounding the Sun, leaving only the outer corona visible.

The Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) instrument on SDO can “fill” this gap, allowing astronomers to study the corona all the way down to the Sun’s surface. The resulting images highlight the ever-changing connections between gas captured by the Sun’s magnetic field and gas escaping into interplanetary space.

The Sun’s magnetic field molds and shapes the corona. Hot solar plasma streams outward in vast loops larger than Earth before plunging back onto the Sun’s surface. Some of the loops expand and stretch bigger and bigger until they break, belching plasma outward.

“The AIA solar images, with better-than-HD quality views, show magnetic structures and dynamics that we’ve never seen before on the Sun,” said Steven Cranmer from CfA. “This is a whole new area of study that’s just beginning.”

Cranmer and Alec Engell, also from CfA, developed a computer program for processing the AIA images above the Sun’s edge. These processed images imitate the blocking-out of the Sun that occurs during a total solar eclipse, revealing the highly dynamic nature of the inner corona. They will be used to study the initial eruption phase of coronal mass ejections as they leave the Sun and to test theories of solar wind acceleration based on magnetic reconnection.

Now, an instrument on board NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), developed by Smithsonian scientists, is giving unprecedented views of the innermost corona 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

“We can follow the corona all the way down to the Sun’s surface,” said Leon Golub from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Previously, solar astronomers could only observe the corona by physically blocking the solar disk with a coronagraph, much like holding your hand in front of your face while driving into the setting Sun. However, a coronagraph also blocks the area immediately surrounding the Sun, leaving only the outer corona visible.

The Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) instrument on SDO can “fill” this gap, allowing astronomers to study the corona all the way down to the Sun’s surface. The resulting images highlight the ever-changing connections between gas captured by the Sun’s magnetic field and gas escaping into interplanetary space.

The Sun’s magnetic field molds and shapes the corona. Hot solar plasma streams outward in vast loops larger than Earth before plunging back onto the Sun’s surface. Some of the loops expand and stretch bigger and bigger until they break, belching plasma outward.

“The AIA solar images, with better-than-HD quality views, show magnetic structures and dynamics that we’ve never seen before on the Sun,” said Steven Cranmer from CfA. “This is a whole new area of study that’s just beginning.”

Cranmer and Alec Engell, also from CfA, developed a computer program for processing the AIA images above the Sun’s edge. These processed images imitate the blocking-out of the Sun that occurs during a total solar eclipse, revealing the highly dynamic nature of the inner corona. They will be used to study the initial eruption phase of coronal mass ejections as they leave the Sun and to test theories of solar wind acceleration based on magnetic reconnection.