A new study published in Nature this week reveals that asteroid surfaces age and redden faster than previously thought — in less than a million years, the blink of an eye for an asteroid. This study has confirmed that the solar wind is the most likely cause of rapid “space weathering” in asteroids. The result will help astronomers relate the appearance of an asteroid to its actual history and identify any after effects of a catastrophic impact with another asteroid.

“Asteroids seem to get a ‘sun tan’ very quickly,” said lead author Pierre Vernazza, “but not, as for people, from an overdose of the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation, but from the effects of its powerful wind.”

It has long been known that asteroid surfaces alter in appearance with time — the observed asteroids are much redder than the interior of meteorites found on Earth — but the actual processes of this space weathering and the timescales involved were controversial.

Thanks to observations of different families of asteroids using the European Southern Observatory’s New Technology Telescope at La Silla and the Very Large Telescope at Paranal, both in Chile, as well as telescopes in Spain and Hawaii, Vernazza’s team have now solved the puzzle.

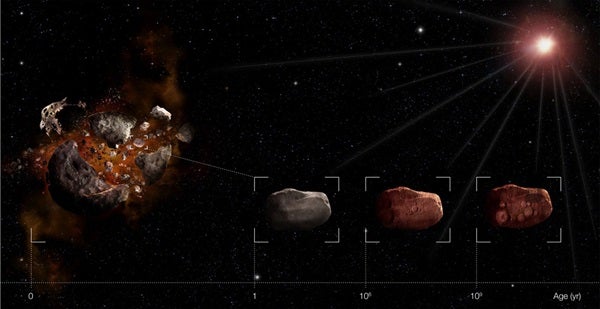

When two asteroids collide, they create a family of fragments with “fresh” surfaces. The astronomers found that these newly exposed surfaces are quickly altered and change color in less than a million years — a short time compared to the age of the solar system.

“The charged, fast-moving particles in the solar wind damage the asteroid’s surface at an amazing rate,” Vernazza said. Unlike human skin, which is damaged and aged by repeated overexposure to sunlight, it is, perhaps rather surprisingly, the first moments of exposure (on the timescale considered) — the first million years — that causes most of the aging in asteroids.

By studying different families of asteroids, the team has also shown that an asteroid’s surface composition is an important factor in how red its surface can become. After the first million years, the surface “tans” much more slowly. At that stage, the color depends more on composition than on age. Moreover, the observations reveal that collisions cannot be the main mechanism behind the high proportion of “fresh” surfaces seen among near-Earth asteroids. Instead, these “fresh-looking” surfaces may be the results of planetary encounters, where the tug of a planet has “shaken” the asteroid, exposing unaltered material.

With these results, astronomers will now be able to understand better how the surface of an asteroid — which often is the only thing we can observe — reflects its history.