My childhood fascination with the night sky led me to study astronomy and physics at university. By my second year, I was operating the telescope atop the physics building, tracking celestial objects — just like astronomy student Kate Dibiasky in the disaster movie Don’t Look Up.

I never imagined I’d also soon find myself alerting others about the dangers my science revealed. Only instead of a fictional asteroid hurtling toward Earth, I was sounding the alarm about the climate crisis.

For decades, scientists have struggled to communicate the urgency of this real and actionable threat in a way that leads to meaningful change. I’ve learned the real challenge isn’t a paucity of scary facts or worried people. Rather, it’s connecting what we know with what we can do — turning knowledge into action. As former United Nations climate chief Christiana Figueres says, “We are only as doomed as we believe ourselves to be.” Yet many people remain unsure of how to respond — and as a result, do nothing.

Changing course

My wake-up call began not at the telescope but in a class I took to fulfill a breadth requirement. At the time, I shared the same vague understanding of climate change most of us have. I knew it was real and human-caused, but I considered it a distant issue. Like a far-off chunk of rock in the asteroid belt, it didn’t feel urgent or even relevant to my life.

Yet in that classroom — a relic of the ’60s, with linoleum floors, beige walls, and those plastic molded chairs with attached desks — I was astonished to learn that climate change isn’t a future threat. It’s affecting us now. Even more surprising, I learned it’s far more than an environmental issue. Climate change is deeply intertwined with human life on this planet, affecting our health, our food, and our water.

It drives economic instability and geopolitical conflicts, exacerbates refugee crises, deepens poverty, and disproportionately harms marginalized communities.

What amazed me most was learning that climate science required the very skill set I was already developing, from decoding the equations of nonlinear fluid dynamics to modeling planetary atmospheres.

“If that’s the case, then how can I not help?” I thought. “Climate change is obviously urgent enough that we will fix it quickly, and then I can go back to studying the universe!” Encouraged, I changed course, applying to atmospheric science graduate programs focusing on research that helped decision-makers make the right choices. After all, surely they would do what we needed them to, once they understood the urgency and scope of the climate crisis — right?

Scientists had known since the 1850s that burning coal, gas, and oil releases heat-trapping gases, wrapping an extra blanket around the planet and causing it to warm. By the 1930s, this warming was already being detected in global temperature records. By the 1960s, the future implications were so concerning that scientists took the unprecedented step of formally warning a U.S. president — Lyndon B. Johnson — about the societal risks of climate change.

In the early 1990s, climate change impacts were starting to become visible. Yet my optimism felt justified at the time. I had every reason to believe meaningful action was not only possible, but imminent. In 1988, NASA scientist (and former astrophysicist) James Hansen testified before Congress that global warming was real and already happening. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was established and, in 1990, released its first scientific assessment report. In 1992, just before I took that climate class, nearly every country in the world signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, pledging to prevent “dangerous human interference” with the climate system.

The climate equation

Yet here we are, 30 years later. There’s been progress, yes — but at nowhere near the scale needed to avert this crisis. Shockingly, over half of all carbon pollution — the primary driver of climate change — has been emitted since 1990. This problem has only accelerated during the years I’ve dedicated my life to addressing it. It’s no wonder so many scientists, including me, are frustrated and appalled at the inadequacy of society’s response to the urgent threat we’ve identified.

In my case, though, that frustration drove me to search for the reason why understanding the science hasn’t been enough to spur action. And it’s this search that ultimately led me to the realization that the “climate equation” we’ve been using to guide our communication efforts is stunningly incomplete. To be explicit, it lacks two key terms that convert scientific urgency into effective action. How could we expect success without them?

Equations help scientists understand, predict, and solve complex problems. But when it comes to activating people to address climate risk, we’ve been relying heavily on one part of the equation while leaving out two essential terms. As a result, it’s like trying to fix a complex machine with just a screwdriver, leaving the hammer and wrench untouched in the toolbox. Without these missing tools, our efforts have fallen short.

The first term, which has dominated our efforts for over a century, is physical science. I think of this as the head: everything we know, encompassing the data, facts, models, and observations we’ve meticulously gathered over decades and even centuries. This term provides essential information, like the fact that never in the history of this planet, going back hundreds of millions of years, has global temperature changed as rapidly as it is now. Earth has been warmer and cooler before, but the speed of today’s changes and the fact that they’re caused by human actions are entirely unprecedented. Climate science also reveals the existence of physical tipping points, critical thresholds that can lead to irreversible changes in the climate system, from ocean circulation shutdown to Amazon rainforest dieback.

But understanding the problem is only part of the equation. To solve it, we need a second term: understanding why it matters. I think of this as the heart. Why? Because knowing what’s happening isn’t enough. As much as we like to believe we’re purely rational beings, the reality is that, as humans, we make decisions based on what we care about, not just what we know. The risks posed by climate change must be connected to what matters most to each of us — our health, homes, families, and future — or they are insufficient to encourage most people to act.

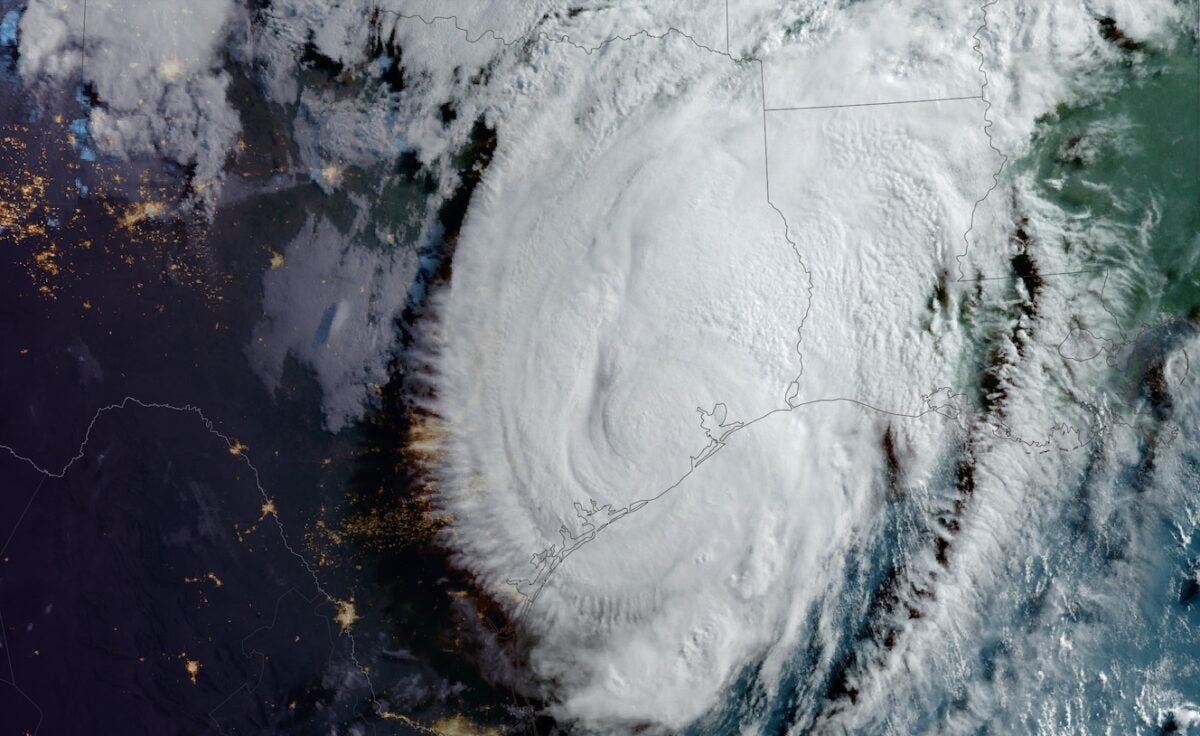

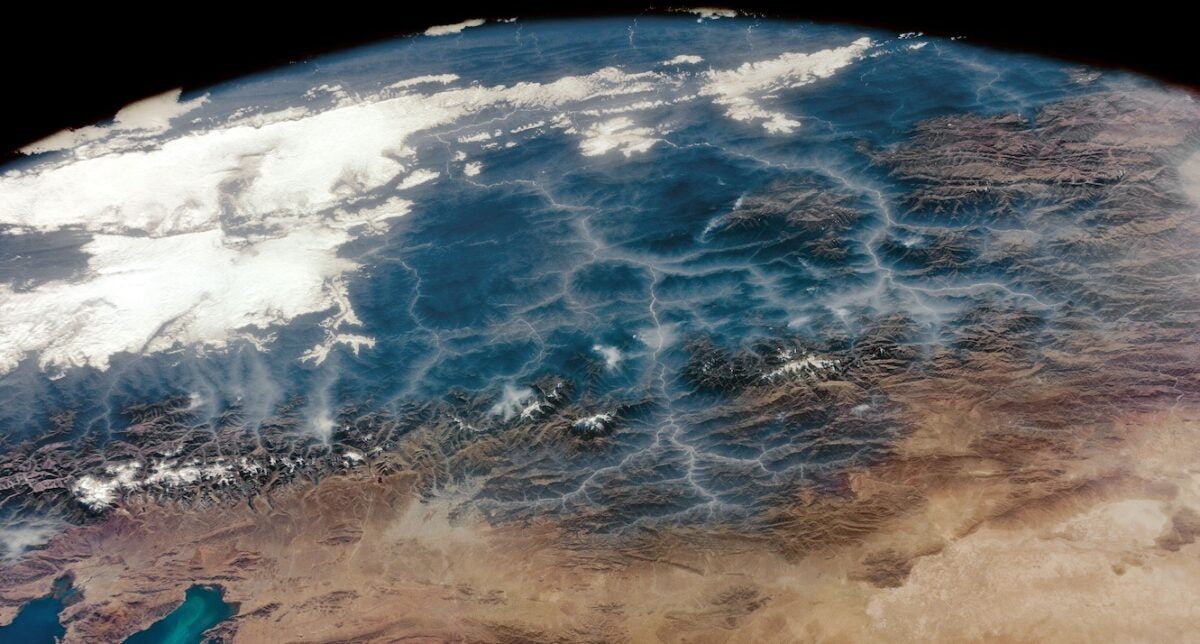

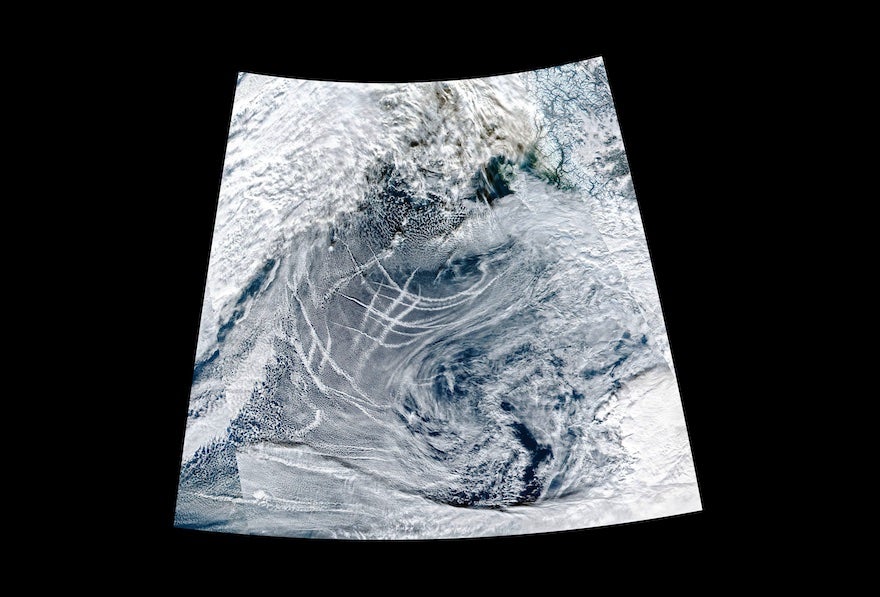

By now, the impacts are evident all around us. Heat waves are more intense and frequent. Wildfire seasons are longer, with blazes burning greater areas. Droughts are stronger and more prolonged. Hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones are intensifying at record speed, powered by energy from record-warm oceans. Heavy downpours occur more often, as warmer air holds more moisture. And people are noticing these shifts: The U.S. now experiences at least one billion-dollar weather and climate disaster every three weeks, on average. In 2023, 9 out of 10 Americans said they’d been personally affected by extreme weather — or, as I call it, “global weirding.”

Even still, many haven’t yet made the crucial connection between what’s happening and how it affects us personally. While nearly three-quarters of Americans acknowledge the climate is changing and are concerned about its impact on future generations, less than half agree that climate change will impact their lives. A similar gap between the head and the heart is evident worldwide. We understand intellectually that the problem is real and urgent, but haven’t fully recognized how it will harm — or is already harming — the people, places, and things we love.

Make no mistake, that harm is already here. For example, did you know that the particulate pollution from fossil fuels alone is reducing the success of in vitro fertilization by 40 percent and contributing to premature births, as well as causing over 8 million deaths around the world every year? Breathing polluted air increases people’s risk of lung and heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and more. And extreme heat not only drives up our power bills and increases the risk of heat stroke for people working or spending time outdoors, but it also affects our sleep and our mental health.

Then there’s the economy, where inflation has driven up food prices; studies have fingerprinted the contribution of climate change to these price hikes. Specialty crops, from bananas to coffee, are under stress, and climate-related extremes wiped out much of the global cocoa harvest as well as significant proportions of the U.K.’s crops in 2023. Insurance rates are skyrocketing thanks to climate-related disasters, with some companies even pulling out of high-risk areas in Florida and California. On a global scale, climate change has already widened the economic gap between the richest and poorest nations, increasing the disparity by as much as 25 percent.

Even astronomy is not immune. As the atmosphere heats up, turbulence is on the rise. This affects air travel, increasing the risk of stomach-dropping bumpy weather, but it also affects astronomical observations from Earth’s surface. Astronomers are already being warned that they need to incorporate climate-change projections into their site selections and prepare for an increase in poor viewing conditions.

This is how to make the head-to-heart connection: by talking about what’s happening now, not in some abstract future; what’s happening here, not “over there” in the metaphorically distant asteroid belt; and what’s relevant to our lives, rather than to the polar bears or the ice sheets.

It’s not just about global temperature or glaciers. It’s about my kid’s health, the air they breathe, and whether they can play outside. It’s not only about sea level rise, but about disrupted commutes and skyrocketing insurance rates. And it’s not only about carbon pollution levels, but about how the food we eat is getting less nutritious as faster-growing crops mean lower nutrient levels, and how our homes, roads, and buildings were designed for a climate that no longer exists. To care about climate change, we don’t need to be scientists, environmentalists, or activists. We only need to be humans living on planet Earth.

Chances are, if you’re reading this you’re already being impacted, whether you know it or not. And that makes you the perfect person to care.

In our hands

Here’s the thing, though: Connecting our heart to our head still isn’t enough. Why not? Because the whole world could be worried, but if we don’t know what to do, we’ll do nothing. And that’s where the majority stands today.

In the U.S., for example, two-thirds of people are worried, but only 8 percent are taking action. That means nearly 60 percent of Americans are worried about the climate but don’t know what to do! That’s why the third term in the equation is crucial: the actions we take in response to our head and our heart. I think of this as the hands, and they are what will determine our future.

When it comes to climate action, there’s no silver bullet. No single solution will fix everything. But there is plenty of what I like to call silver buckshot: smaller but meaningful solutions that, when combined, have the power to tackle this crisis and build a better world.

Imagine the atmosphere as a swimming pool. The level of heat-trapping gases is like the water in the pool. Before the Industrial Revolution, the water level was just right. But then we stuck a giant hose in the pool and ever since, we’ve been turning the hose up every year. Our emissions come from burning coal, gas, and oil, as well as through deforestation and unsustainable food systems. Now, the water’s so high that our toes can’t touch the bottom anymore.

So, what do we need to do? Three things: First, we need to turn off the hose. We can do this by improving energy efficiency, shifting to renewable energy, stopping deforestation, and making our food systems sustainable. This can include everything from signing up for a clean power plan for our home to advocating for sensible land use policies in our county, township, or region.

But the pool also has a drain: nature. By investing in nature, we can help it absorb carbon from the atmosphere and store it in ecosystems and soil. This means protecting old-growth forests, restoring damaged ecosystems, adopting climate-smart regenerative agricultural practices to turn our food systems into carbon sinks, and yes — planting trees, too!

There’s one more step, though. The water level in the pool is already too high, and many people are suffering. Climate change affects us all, but not equally. The poorest and most vulnerable are the hardest hit. That’s why building resilience — akin to teaching people to swim — is just as critical. We need to adapt our infrastructure, make our food and water systems resilient, and help people and nature adapt to the changes that are already too late to avoid. Whether improving disaster-response systems or greening urban areas to protect people from heat and floods, there are many ways we can build that resilience.

There are so many options to turn off the hose, make the drain bigger, and learn how to swim, from building solar farms and public transportation to cutting food waste and educating overlooked women and girls. And the best part? Most of these solutions make the world better, full stop. They give us cleaner air, more abundant water, and more affordable energy. They protect us from the growing disasters caused by climate change, while also improving our physical and mental health. Many solutions also address poverty, reduce inequalities, and restore ecosystems rather than degrade them.

Using our voices

The systemic changes we need are clear, but they raise an obvious question: “What can I do about climate change?” After all, you might think, “I’m just one person, and not a particularly influential one.”

This sense of helplessness and lack of agency is echoed in Don’t Look Up, as scientists’ efforts fail to change the course of disaster. Despite attempts to warn the public, the asteroid strike eventually wipes out life on Earth.

While this allegory offers no hope, history holds a different lesson. Large societal changes at the scale we need have happened before. And those who led these movements — from Susan B. Anthony to Mahatma Gandhi to Nelson Mandela — weren’t rich or famous. But they used their voices, inspired millions more to use theirs as well, and they changed the world. Our lives are materially different because of what these individuals accomplished. If they could do it, so can we.

That’s why, to transform the systems that shape our choices, I’m convinced our voices are the most powerful tool we have. Through our voices, our votes, and our choices, we can help make the best and most sustainable options for individuals the most accessible and affordable, too. Charging an electric car should be easier than finding a gas station. Healthy food like fresh fruits, vegetables, and sustainable fish should cost less and be more readily available than fast-food burgers made from meat farmed on what used to be Amazonian rainforest. Energy-efficient appliances should be cheaper than wasteful ones, and repairing what we already own should be simpler than buying new things. And all electricity should be clean — we shouldn’t even have to think about that!

As individuals, our actions absolutely matter. But for real change, we must look beyond our personal carbon footprint. It’s not only about our own behavior — it’s about creating the conditions that make sustainable choices the easiest and most obvious path for everyone. As environmentalist Bill McKibben puts it, “The most important thing an individual can do right now is not be such an individual.” Collective action is far more powerful than isolated efforts.

Together as one

How do we ensure these solutions happen sooner rather than later? Research identifies social tipping points that can catalyze systemic change: removing fossil-fuel subsidies, divesting from assets linked to fossil fuels and revealing their moral implications, building carbon-neutral cities, and strengthening climate education and engagement.

As individuals, we have a role to play in this process. Who is lobbying organizations stop investing in fossil fuels? Who is highlighting the moral costs of dirty energy and their impacts on our health and our future? Who is advocating for the sustainable city programs and practices, from bike lanes and high-density development to clean energy and composting, needed to become truly carbon-neutral? Who is pushing for climate education and — when a school or a university adopts it — making it happen? The answer, in each of these cases, is individuals. The success of systemic change relies on individuals advocating for these changes at every level of governance and society.

For years, I felt the weight of a crisis too vast to fix alone. I struggled to understand why knowing the science wasn’t enough. But now the equation is clear: We must connect our heads to our hearts, then turn that urgency into action with our hands.

As Jane Goodall says, “only when our clever brain and our human heart work together” can we create the momentum needed to tackle the climate crisis and build a better, safer, healthier, and greener future. That is the world I want — for my child, for myself, and for everyone who shares this planet with us.

We can’t stop the climate asteroid alone. But I’m certain we can do it together.