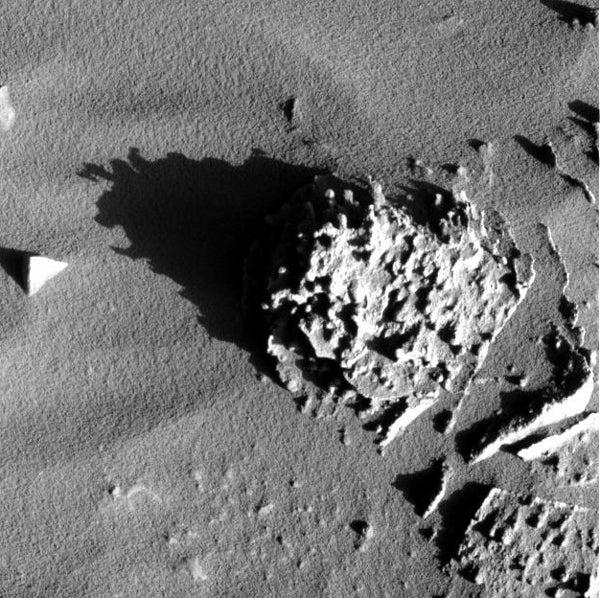

Mars rover Spirit, poking among the rocks at the foot of the Columbia Hills, has found an intriguing-looking rock that scientists dubbed Pot of Gold. It earned that name because, as team scientist Larry Soderblom of the U.S. Geological Survey says, “This is the prize at the end of our rainbow.”

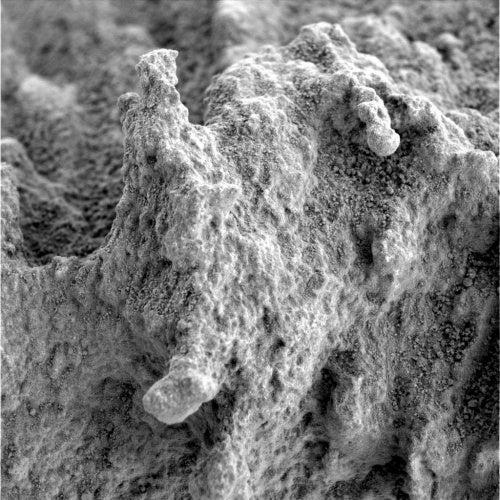

As they look closer at Pot of Gold, however, mission scientists find themselves astonished at this rock’s peculiarities. It has nodules a few millimeters across attached to the ends of stalks of rock perhaps an inch long. Seen close-up by the rover’s microscopic imager, the nodules are not round like the famed “blueberries” discovered by the other rover in Meridiani Planum. In fact, scientists are at a loss to explain Pot of Gold’s nodules at all.

“I cannot tell you what these nuggets are,” said Mars rover chief scientist Steve Squyres of Cornell University, at a press briefing June 25. “I don’t know how these things formed, and it’s driving me nuts!”

Pot of Gold appears heavily weathered and, as determined by the rover’s Mössbauer spectrometer, it contains hematite. This is the iron mineral abundant in Mars’s Meridiani Planum, where it was produced by the action of an ocean or lake on evaporite deposits rich in salts and sulfates. Gusev, however, has proven so far to be quite dry, with scientists finding only relatively minor effects of water on some rocks.

As they struggle to understand this particular rock, scientists plan to spend as much time as needed examining it and other rocks in the vicinity. “We’re going to go very methodically through the geochemistry,” says Squyres. “We’ll examine Pot of Gold and perhaps a few targets within a few meters.”

As a backup, project engineers are developing ways to drive Spirit using five wheels instead of its normal six. In any case, says Squyres, “The lubrication needs to take place before we drive more than a few meters — before we hit the road again.”

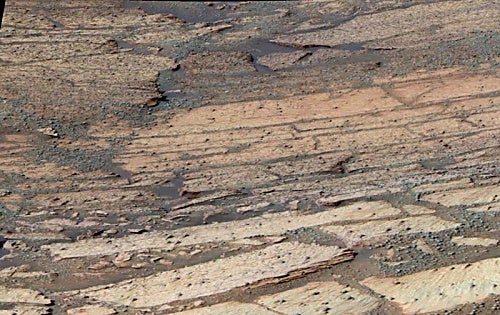

Half a planet away, Opportunity remains nose-down on the inner wall of Endurance Crater. It is looking down on a 23° slope, just above a steeper section that slopes 35° to 40°. Mission scientists are examining layers of rock that lie beautifully exposed in a classic stratigraphic sequence on the crater wall.

The layer closest to the rover, and therefore highest and youngest in the sequence, is the same rock unit that was exposed in Eagle Crater, Opportunity’s landing site. Research has already shown that this unit was laid down under wet conditions, probably as a shallow, salty sea ebbed and surged across the site. Initial results on the older layers seen here, however, suggest that at least some of them were deposited under dry, wind-blown conditions.

The next step will be examine each of the layers closely and characterize the environment it was deposited within. This will require the rover to descend farther and onto the steeper slope. Mission planners at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, using the lab’s “Mars yard,” have tested the rover’s ability to negotiate the slopes — and Opportunity should be able to drive forward over the slope and, just as important, back up across it again.

Both rovers are making wonderful discoveries. As Squyres says, “It’s like the missions have started all over again.”