Astronomers have discovered that galaxies in the distant universe continuously ingested their star-making fuel over long periods of time. This goes against previous theories that galaxies devoured their fuel in quick bursts after run-ins with other galaxies.

“Our study shows the merging of massive galaxies was not the dominant method of galaxy growth in the distant universe,” said Ranga-Ram Chary from NASA’s Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. “We’re finding this type of galactic cannibalism was rare. Instead, we are seeing evidence for a mechanism of galaxy growth in which a typical galaxy fed itself through a steady stream of gas, making stars at a much faster rate than previously thought.”

According to Chary’s findings, these grazing galaxies fed steadily over periods of hundreds of millions of years and created an unusual amount of plump stars, up to 100 times the mass of our Sun.

“This is the first time that we have identified galaxies that supersize themselves by grazing,” said Hyunjin Shim from Spitzer Science Center. “They have many more massive stars than our Milky Way galaxy.”

Galaxies like our Milky Way are giant collections of stars, gas, and dust. They grow in size by feeding off gas and converting it to new stars. A long-standing question in astronomy is: Where did the distant galaxies that formed billions of years ago acquire this stellar fuel?

The most favored theory was that galaxies grew by merging with other galaxies, feeding off gas stirred up in the collisions.

Chary and his team addressed this question by using Spitzer to survey more than 70 remote galaxies that existed 1 to 2 billion years after the Big Bang. (Our universe is approximately 13.7 billion years old.) To the surprise of the astronomers, these galaxies were blazing with a type of light called H-alpha (Hα), radiation from hydrogen gas that has been hit with ultraviolet light from stars. High levels of Hα indicate rigorous star formation. Seventy percent of the surveyed galaxies show strong signs of the Hα signature in contrast to only 0.1 percent of galaxies in our local universe.

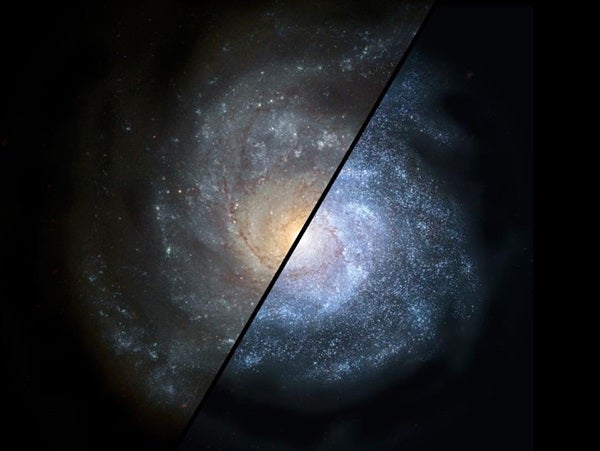

Previous studies using ultraviolet-light telescopes found about six times less star formation than Spitzer, which sees infrared light.

Scientists think this may be due to large amounts of obscuring dust, through which infrared light can sneak. Spitzer opened a new window onto the galaxies by taking long-exposure infrared images of a patch of sky called the GOODS fields, named for Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey.

Astronomers have discovered that galaxies in the distant universe continuously ingested their star-making fuel over long periods of time. This goes against previous theories that galaxies devoured their fuel in quick bursts after run-ins with other galaxies.

“Our study shows the merging of massive galaxies was not the dominant method of galaxy growth in the distant universe,” said Ranga-Ram Chary from NASA’s Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. “We’re finding this type of galactic cannibalism was rare. Instead, we are seeing evidence for a mechanism of galaxy growth in which a typical galaxy fed itself through a steady stream of gas, making stars at a much faster rate than previously thought.”

According to Chary’s findings, these grazing galaxies fed steadily over periods of hundreds of millions of years and created an unusual amount of plump stars, up to 100 times the mass of our Sun.

“This is the first time that we have identified galaxies that supersize themselves by grazing,” said Hyunjin Shim from Spitzer Science Center. “They have many more massive stars than our Milky Way galaxy.”

Galaxies like our Milky Way are giant collections of stars, gas, and dust. They grow in size by feeding off gas and converting it to new stars. A long-standing question in astronomy is: Where did the distant galaxies that formed billions of years ago acquire this stellar fuel?

The most favored theory was that galaxies grew by merging with other galaxies, feeding off gas stirred up in the collisions.

Chary and his team addressed this question by using Spitzer to survey more than 70 remote galaxies that existed 1 to 2 billion years after the Big Bang. (Our universe is approximately 13.7 billion years old.) To the surprise of the astronomers, these galaxies were blazing with a type of light called H-alpha (Hα), radiation from hydrogen gas that has been hit with ultraviolet light from stars. High levels of Hα indicate rigorous star formation. Seventy percent of the surveyed galaxies show strong signs of the Hα signature in contrast to only 0.1 percent of galaxies in our local universe.

Previous studies using ultraviolet-light telescopes found about six times less star formation than Spitzer, which sees infrared light.

Scientists think this may be due to large amounts of obscuring dust, through which infrared light can sneak. Spitzer opened a new window onto the galaxies by taking long-exposure infrared images of a patch of sky called the GOODS fields, named for Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey.