The images are part of the Galactic Legacy Infrared Mid-Plane Survey Extraordinaire (Glimpse 360) project, which is mapping the celestial topography of our galaxy. The map and a full 360° view of the Milky Way plane will be available later this year. Anyone with a computer may view the Glimpse images and help catalog features.

We live in a spiral collection of stars that is mostly flat, like a vinyl record, but it has a slight warp. Our solar system is located about two-thirds of the way out from the Milky Way’s center, in the Orion Spur, an offshoot of the Perseus spiral arm. Spitzer’s infrared observations are allowing researchers to map the shape of the galaxy and its warp with the most precision yet.

While Spitzer and other telescopes have created mosaics of the galaxy’s plane looking in the direction of its center before, the region behind us, with its sparse stars and dark skies, is less charted.

“We sometimes call this flyover country,” said Barbara Whitney, an astronomer from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “We are finding all sorts of new star formation in the lesser-known areas at the outer edges of the galaxy.”

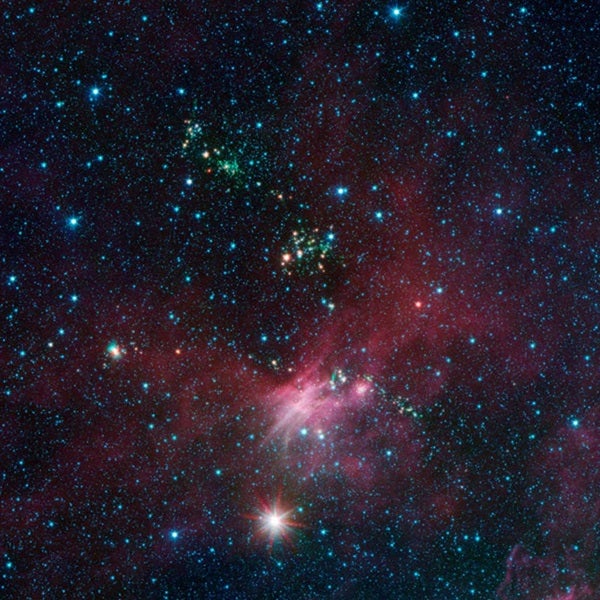

Whitney and colleagues are using the data to find new sites of youthful stars. For example, they spotted an area near Canis Major with 30 or more young stars sprouting jets of material, an early phase in their lives. So far, the researchers have identified 163 regions containing these jets in the Glimpse 360 data, with some of the young stars highly clustered in packs and others standing alone.

Robert Benjamin is leading a University of Wisconsin team that uses Spitzer to more carefully pinpoint the distances to stars in the galaxy’s hinterlands. The astronomers have noticed a distinct and rapid drop-off of red giants, a type of older star, at the edge of the galaxy. They are using this information to map the structure of the warp in the galaxy’s disk.

“With Spitzer, we can see out to the edge of the galaxy better than before,” said Benjamin. “We are hoping this will yield some new surprises.”

Thanks to Spitzer’s infrared instruments, astronomers are capturing improved images of those remote stellar lands. Data from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) are helping fill in gaps in the areas Spitzer did not cover. WISE was designed to survey the entire sky twice in infrared light, completing the job in early 2011, while Spitzer continues to probe the infrared sky in more detail. The results are helping to canvas our galaxy, filling in blanks in the outer expanses where not much is known.

Glimpse 360 already has mapped 130° of the sky around the galactic center.

Members of the public continue scouring images from earlier Glimpse data releases in search of cosmic bubbles indicative of hot massive stars. Astronomers’ knowledge of how massive stars influence the formation of other stars is benefitting from this citizen science activity, called The Milky Way Project. For instance, volunteers identified a striking multiple bubble structure in a star-forming region called W39. Follow-up work by the researchers showed the smaller bubbles were spawned by a larger bubble that had been carved out by massive stars.

“This crowdsourcing approach really works,” said Charles Kerton of Iowa State University in Ames. “We are examining more of the hierarchical bubbles identified by the volunteers to understand the prevalence of triggered star formation in our galaxy.”