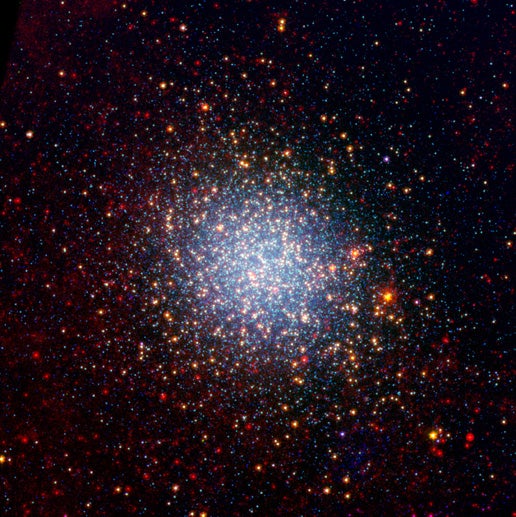

Millions of clustered stars glisten like an iridescent opal in a new image from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope.

Called Omega Centauri, this sparkling orb of stars is like a miniature galaxy. It is the biggest and brightest of the more than 150 similar objects, called globular clusters, that orbit around the outside of our Milky Way galaxy. Stargazers at southern latitudes can spot the stellar gem with the naked eye in the constellation Centaurus.

While the visible-light observations highlight the cluster’s millions of jam-packed stars, Spitzer’s infrared eyes reveal the dustier, more evolved stars tossed throughout the region.

“Now we can see which stars form dust and can begin to understand how the dust forms and where it goes once it is expelled from a star,” says Martha Boyer of the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. Boyer is lead author of a paper about Omega Centauri appearing in the April issue of the Astronomical Journal. “Surprisingly, Spitzer revealed fewer of these dusty stars than expected.”

Globular clusters are some of the oldest objects in our universe. Their stars are more than 12 billion years old, and, in most cases, formed all at once when the universe was just a toddler. Omega Centauri is unusual in that its stars are of different ages and possess varying levels of metals, or elements heavier than boron. Astronomers say this points to a different origin for Omega Centauri than other globular clusters: they think it might be the core of a dwarf galaxy that was ripped apart and absorbed by our Milky Way long ago.

In the new picture of Omega Centauri, the red- and yellow-colored dots represent the stars revealed by Spitzer. These are the more evolved, larger, dustier stars, called red giants. The stars colored blue are less evolved, like our own Sun, and were captured by both Spitzer’s infrared eyes and in visible light by the National Science Foundation’s Blanco 4-meter telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. Some of the red spots in the picture are distant galaxies beyond our own.

“As stars age and mature into red giants, they form dust grains, which play a vital role in the evolution of the universe and the formation of rocky planets,” says Jacco van Loon, the study’s principal investigator at Keele University in England. “Spitzer can see this dust, and it was able to resolve individual red giants even in the densest central parts of the cluster.”