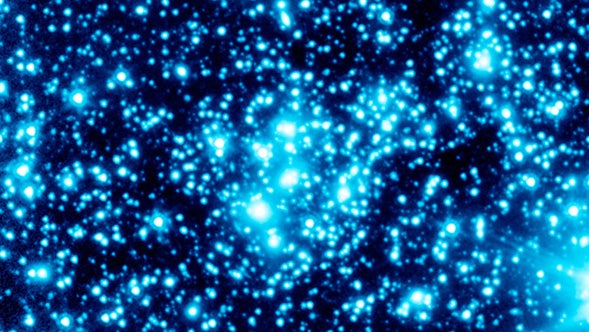

The faintness of the earliest, most distant galaxies makes studying them a challenge. Frontier Fields, however, can spot these primordial galaxies courtesy of foreground clusters of galaxies, whose gargantuan mass and gravity form cosmic “zoom lenses.” Peering through these gravitational lenses is giving astronomers an unprecedented view of the galactic dawn.

“Our overall science goal with the Frontier Fields is to understand how the first galaxies in the universe assembled,” said Peter Capak from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. “This pursuit is made possible by how massive galaxy clusters warp space around them, kind of like when you look through the bottom of a wine glass.”

Although astronomers have relied on this cosmic lensing for many years to turn up distant galactic quarry, Frontier Fields takes the practice to a new level. The project has selected the most massive and distant clusters on record, thus offering the highest magnification and deepest probe of the early universe available.

Plus, Frontier Fields will further characterize the foreground clusters to better gauge the lenses’ magnifying, as well as distorting, effects. On average, the gravitational warping of space by foreground clusters magnifies background galaxies four to 10 times. But some galaxies studied via Frontier Fields will be magnified on the order of a hundred times.

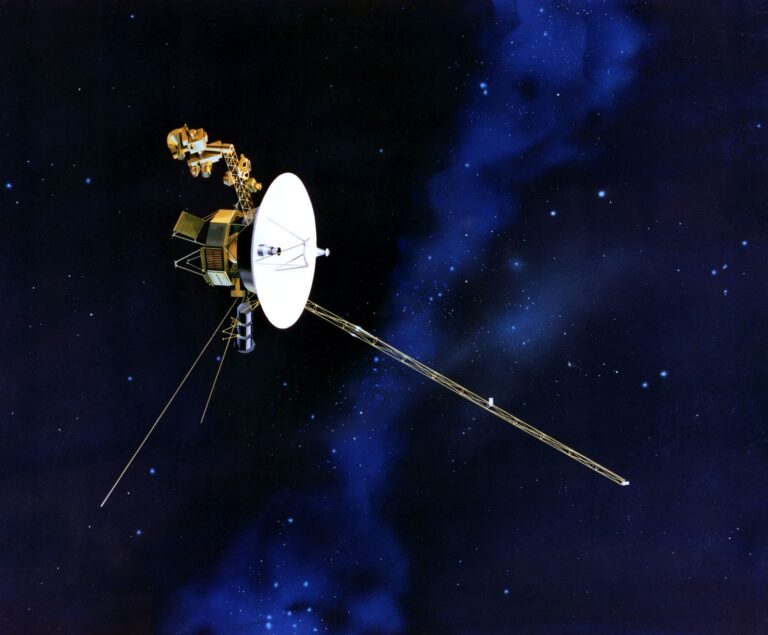

NASA’s Great Observatories will view the cluster galaxies and background galaxies in different wavelengths of light, each of which carries important scientific information. Spitzer observes in longer-wavelength infrared light; Hubble in shorter infrared and optical light; and Chandra in high-energy X-rays.

The infrared light captured by Spitzer serves two key purposes. Firstly, infrared light is an indicator of the number of stars in a galaxy, which speaks to the galaxy’s overall mass. In the case of extremely distant galaxies, the optical light from their stars has been stretched out, or “redshifted,” into infrared wavelengths as a result of the expansion of the universe. “Spitzer basically measures the mass of galaxies,” said Capak. “Because of the wavelengths it works in, Spitzer is the only instrument capable of making mass measurements of galaxies this far away.”

Secondly, Spitzer can help determine if certain galaxies also observed by Hubble are in fact the faroff early galaxies of interest or just nearby galaxies. “Spitzer and Hubble can tell if galaxies discovered in the Frontier Fields are really at the edge of the universe or not,” said Capak.

Hubble and Spitzer scientists envisioned this sort of synergy when the Frontier Fields were conceived in 2012. “This program exemplifies the combined strength of NASA’s Great Observatories when it comes to digging deep into the distant universe,” said Jennifer Lotz from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

Chandra’s role in Frontier Fields, meanwhile, is to provide a detailed map of the hot X-ray-emitting gas in the galaxy clusters. Doing so will help further pin down their masses. Spitzer will be integral to this aspect of the project as well by presenting astronomers with an overview of the stars in the clusters’ galaxies.

Observations of the first Frontier Field cluster, Abell 2744, have been completed. Work is now underway on another cluster and two more are slated for summer. The Abell 2744 effort has already resulted in the discovery of one of the most distant galaxies ever seen, dubbed Abell2744 Y1. This tiny, infant galaxy was witnessed at a time when the 13.8 billion-year-old universe was a mere 650 million years old. Frontier Fields is expected to reveal many other similarly primeval galaxies in the critical galaxy-forming epoch shortly after the Big Bang.