Scientists have yet to see anything quite like the dark spots; their presence has piqued the interest of the New Horizons science team due to the remarkable consistency in their spacing and size. While the origin of the spots is a mystery for now, the answer may be revealed as the spacecraft continues its approach to the mysterious dwarf planet. “It’s a real puzzle — we don’t know what the spots are, and we can’t wait to find out,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder. “Also puzzling is the longstanding and dramatic difference in the colors and appearance of Pluto compared to its darker and grayer moon Charon.”

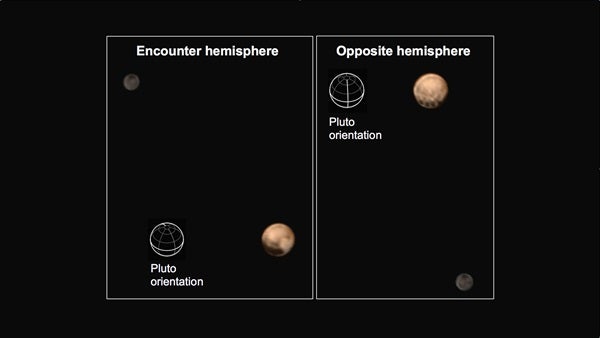

New Horizons team members combined black-and-white images of Pluto and Charon from the spacecraft’s Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) with lower-resolution color data from the Ralph instrument to produce these views. We see the planet and its largest moon in approximately true color, that is, the way they would appear if you were riding on the New Horizons spacecraft. About half of Pluto is imaged, which means features shown near the bottom of the dwarf planet are at approximately at the equatorial line.

Meanwhile, the spacecraft is getting a final “all clear” as it speeds closer to its historic July 14 flyby of Pluto and the dwarf planet’s five moons.

After seven weeks of detailed searches for dust clouds, rings, and other potential hazards, the New Horizons team has decided the spacecraft will remain on its original path through the Pluto system instead of making a late course correction to detour around any hazards. Because New Horizons is traveling at 30,800 mph (49,600 kph), a particle as small as a grain of rice could be lethal.

“We’re breathing a collective sigh of relief knowing that the way appears to be clear,” said Jim Green, director of planetary science at NASA. “The science payoff will be richer as we gather data from the optimal flight path, as opposed to having to conduct observations from one of the backup trajectories.”

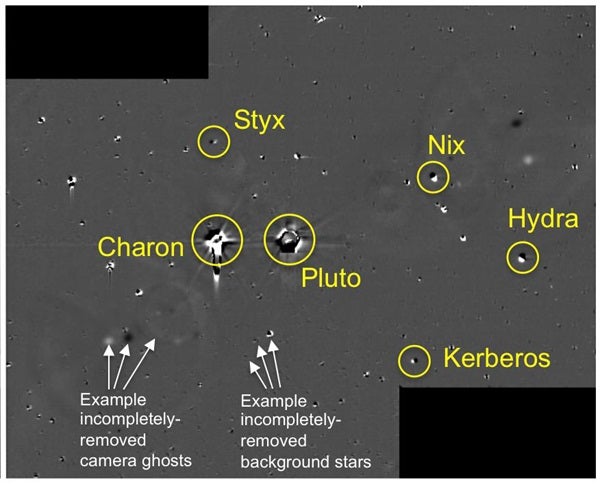

Mission scientists have been using the spacecraft’s most powerful telescopic camera, the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), to look for potential hazards, such as small moons, rings, or dust, since mid-May. The decision on whether to keep the spacecraft on its original course or adopt a Safe Haven by Other Trajectory, or “SHBOT” path, had to be made this week since the last opportunity to maneuver New Horizons onto an alternate trajectory is July 4.

“Not finding new moons or rings present is a bit of a scientific surprise to most of us,” Stern said. “But as a result, no engine burn is needed to steer clear of potential hazards. We presented these data to NASA for review and received approval to proceed on course and plan. We are ‘go’ for the best of our planned Pluto encounter trajectories.”

New Horizons formed a hazard analysis team in 2011 after the discovery of Pluto’s fourth moon, Kerberos, raised concerns the cratering of these moons by small debris from the outer area of the solar system known as the Kuiper Belt could spread additional hazardous debris into New Horizons’ path. Mission engineers retested spare spacecraft blanketing and parts back on Earth to determine how well they would stand up to particle impacts, and scientists modeled the likely formation and locations of rings and debris in the Pluto system. By the time New Horizons’ cameras were close enough to Pluto to start the search last month, the team had already estimated the chances of a catastrophic incident at far less than 1 percent.

The images used in the latest searches that cleared the mission to stay on its current course were taken June 22, 23 and 26. Pluto and all five of its known moons are visible in the images, but scientists saw no rings, new moons, or hazards of any kind. The hazards team determined that satellites as faint as about 15 times dimmer than Pluto’s faintest known moon, Styx, would have been seen if they existed beyond the orbit of Pluto’s largest and closest moon, Charon.

If any rings do exist, the hazard team determined they must be extremely faint, reflecting less than one 5-millionth of the incoming sunlight.

“The suspense — at least most of it — is behind us,” says John Spencer of SwRI, who leads the New Horizons hazard analysis team. “As a scientist, I’m a bit disappointed that we didn’t spot additional moons to study, but as a New Horizons team member I am much more relieved that we didn’t find something that could harm the spacecraft. New Horizons already has six amazing objects to analyze in this incredible system.”

While the lack of new moons was unexpected, finding frozen methane on Pluto’s surface was not. Earth-based astronomers first observed the chemical compound on the distant planet in 1976.

“We already knew there was methane on Pluto, but these are our first detections,” said Will Grundy, the New Horizons Surface Composition team leader with the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. “Soon we will know if there are differences in the presence of methane ice from one part of Pluto to another.”

Methane is an odorless, colorless gas that is present underground and in the atmosphere on Earth. On Pluto, methane may be primordial, inherited from the solar nebula from which the solar system formed 4.5 billion years ago. Methane was originally detected on Pluto’s surface by a team of ground-based astronomers led by New Horizons team member Dale Cruikshank, of NASA’s Ames Research Center, Mountain View, California.