I’ve always found it hard to explain to people what my real job was.

One year, as a guest at San Diego Comic-Con, I was sharing a ride to the venue with a fellow guest, whom I did not know. “So, what do you do?” she asked, while staring disinterestedly out the car window. I took the easy way out and said I was an indie film producer, which is also true.

She rolled her eyes and said, “Hmph. Boring. Everyone in California is a film producer!”

A little irked, I added, “But mostly, I’m a meteorite hunter. I travel the world looking for rocks that have fallen out of the sky.”

“What!?” she exclaimed, both incredulous and bewildered.

Reactions like that have been a constant in my career. I never met a person who was not interested in spending some time with a space rock. If I put a meteorite in someone’s hand at a science fair, an astronomy convention, or even Comic-Con, I was always met with wonder.

When you cover, hunt, or deal in meteorites, that is the real value of these cosmic relics: wonder.

The basics of meteorites

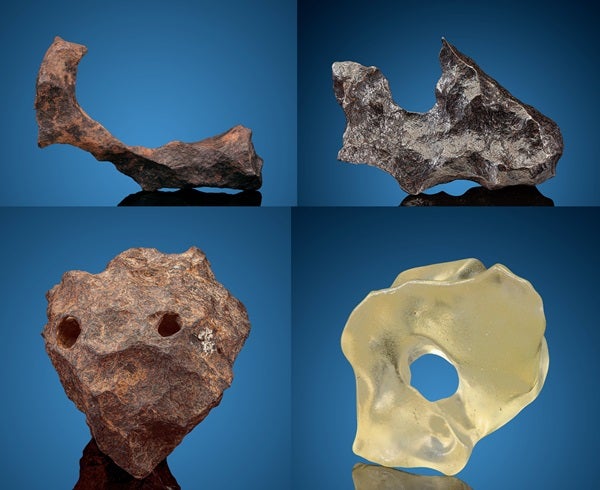

Meteorites, which are space rocks that reach Earth’s surface, are divided into three main groups — irons, stones, and stony-irons. While organizing things into families is a fundamental part of science, the names of these meteorite groups fail to convey their true diversity and mystery. It’s a bit like if ornithologists were to divide all the beautifully diverse species of birds into simply “the big ones” and “the little ones.”

The stony-iron class, for example, consists of two sub-groups: pallasites and mesosiderites. However, these two rare meteorite types do not, in fact, have much to do with each other. Pallasites formed within asteroids, where molten interiors meet mantle. Meanwhile, mesosiderites may have been forged when country-sized asteroids catastrophically collided, battering themselves together into a new kind of matrix.

Meanwhile, stones, viewed as the “most common” meteorite type, comprise so many sub-groups it’s almost dizzying. Carbonaceous chondrites, for example, are ancient, largely unchanged relics from the beginning of the solar system. These originated on asteroids similar to OSIRIS-Rex’s destination, Bennu. But carbonaceous chondrites could hardly be more different than martian meteorites, which are essentially cooled lava blasted off the surface of the Red Planet.

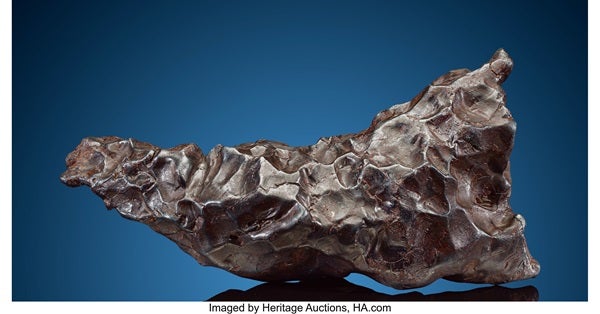

Then there are iron meteorites. Once the molten interiors of asteroids, irons are the jackpot for me. Dense, heavy, and alien, they are often pulverized into fantastical shapes during their harrowing flights though Earth’s atmosphere.

In other words, the characteristics and origin stories of different meteorites are as unique and varied as the fabulous and often remote places where they land. And that’s why I love collecting them.

My road to Meteorite Men

Meteorites have enthralled me since I was a child. But it wasn’t until my early thirties that I set out to hunt them for real. It was films such as King Solomon’s Mines and Lawrence of Arabia that must have instilled in me the need to adventure in far-off — and, preferably, slightly dangerous — places. In an era before streaming, or even VCRs, these movies were rebroadcast during the holidays of my youth. And the brilliant deserts and grandeur of unknown landscapes seemed particularly intoxicating when viewed from gray and rainy old London.

I didn’t know much about hunting meteorites then. But I was lucky and determined; I found a few meteorites on my own. Then, in 1996, a curious individual on the internet found me. His name was Steve Arnold, and he told me he was a full-time meteorite hunter.

I was awestruck. He was very nonchalant about it, as if anyone could do it. Although that may not be true, Arnold nonetheless kickstarted my career as a meteorite hunter. I joined him on a sometimes terrifying journey across Chile’s Atacama Desert in a two-wheel drive Toyota, which I do not recommend attempting. However, during the three-week search, we found hundreds of small meteorites. I knew I could never go back to normal life again. I was hooked on the thrill of the expedition, especially if it took me far, far out into the empty desert, much like in those films I had loved as a kid.

Years later, Arnold and I would star together in a hit television series for Science Channel called Meteorite Men.

Over the years, I have crossed the Sahara in a battered Land Rover. I have been dropped by helicopter into a 35-million-year-old impact crater in Siberia. I have found a 69-pound iron meteorite in the Arctic that was transported there by a glacier during the last ice age. And I have picked up zoomorphic space rocks (those shaped into animal forms) from the surface of Australia’s timeworn Nullarbor Plain. Always, my goal was to get to the most inaccessible places where meteorites had fallen, find them, and bring them home.

It is not only the act of collecting meteorites that has driven me across six continents, but also the desire to explore the history of the others’ collections. Space rocks from historic collections are highly prized by enthusiasts, perhaps because they give us a tangible link to those who have gone before us, those who had carefully curated the specimens so they would survive through the centuries and continue to be admired today.

A meteorite auction for the ages

It has been nearly 30 years since my first meteorite find. The largest whole meteorite I recovered was a 273-pound (124 kilogram) pallasite in Kansas, which I found with Arnold and documented on Meteorite Men. The smallest, a witnessed fall from Illinois named Park Forest, weighed 0.2 grams, or 1/140th of an ounce.

Wherever my personal collecting bug came from, it is now time for my collection to move on to some place new. On June 22, 2022, Heritage Auctions in Dallas will offer my personal meteorites at auction. The collection that has meant everything to me will head back out into the world on a new journey — not as long as the trip that brought the meteorites to Earth, but hopefully a trip that will land them in new and enthusiastic hands.

Part of the proceeds from this auction will be donated to the children’s charity Beads of Courage and the educational science and paleontology museum, Texas Through Time, as I have seen both organizations do great good in the world over the years.

Auction highlights

Below are what I consider some of the auction highlights.

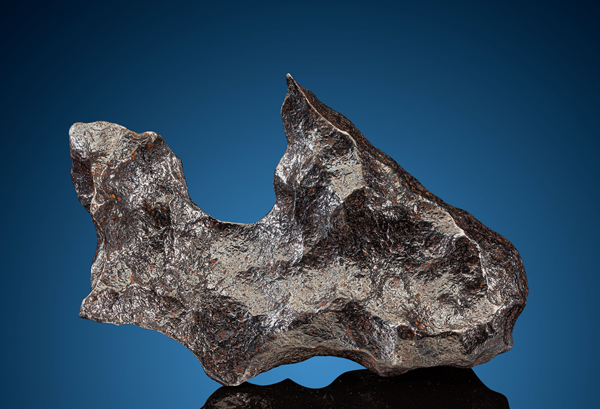

Sikhote-Alin “Flying Wing” (Lot 72028)

My favorite meteorite is Sikhote-Alin. It fell in eastern Siberia in February 1947 and the impact formed approximately 100 distinct craters. A large proportion of the meteoritic material was shattered into fragments upon impact, but some pieces landed as whole, undamaged individuals, their surfaces covered in gentle indentations created when their outer layer melted in flight. The “Flying Wing” shows such features, known as regmaglypts. An exceptionally large and complete whole meteorite that fell without fragmenting, in terms of size, it would likely fall in the top 1 percent of all Sikhote-Alins ever recovered. Extensive hunting at the fall site for decades means no new pieces are expected to be found. It is extremely rare to see a Sikhote-Alin of this size and quality. This piece has been in my collection for more than 20 years.

“Meteorite Men” F-75 Metal Detector (Lot 72074)

Auctions should be fun and exciting and I wanted this one to be an event. I have, therefore, included many prized items from TV’s Meteorite Men, including my beloved Fisher F-75 metal detector. This unit traveled the world with me and was my primary detector on the show. I have found more meteorites with this than every other detector I’ve owned put together. I wish the new owner good hunting!

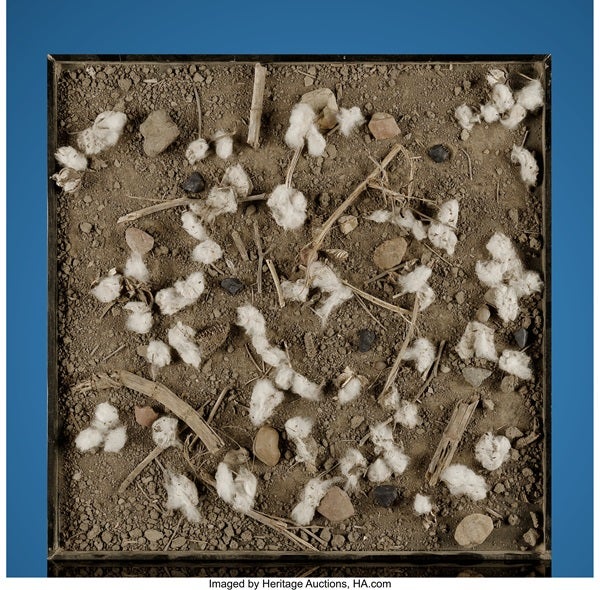

The Ash Creek Diorama (Lot 72104)

On February 15, 2009, I rushed to McLennan County, Texas, after a daytime fireball was seen (a news cameraman filming a sports event captured video footage of the event). I was one of the first people to reach the fall site, and I found a number of perfect, black, fusion-crusted meteorites that had only been on our planet for a few days! I wanted to recreate the excitement of that experience, so I also collected soil, stones, twigs, and cotton from the site. I was then commissioned by the Challenger Space Center Arizona to design and curate a meteorite exhibit for them: “They Came from Outer Space.” This diorama of the meteorite, known as Ash Creek, was created specifically for that exhibit and was seen by thousands of visitors. I hope this unique collection might go to another museum where it can help people understand exactly what freshly fallen meteorites look like. There are five genuine Ask Creek meteorites included in the diorama.

Studying and searching for meteorites has been the great adventure of my life. When I first set out on those expeditions, I was entirely focused on the prize: finding space rocks. Today, looking back through my memories of exploring deserts, tundras, mountains, and oh so many dig holes, I realize the things I’m most grateful for are the moments of joy when a meteorite was found, or a long-dreamed-of impact crater was glimpsed for the first time.

As my meteorite collection goes out into the world on June 22, I wish for the new owners to experience that kind of joy, too.

The Geoff Notkin Collection of Meteorites Signature Auction is open for online bidding at ha.com/notkin and closes on June 22, 2022.