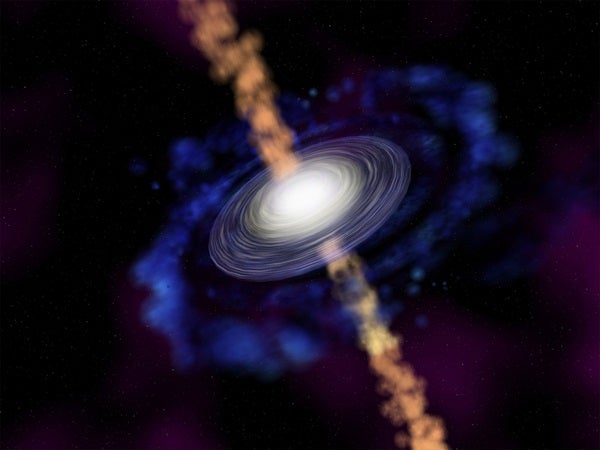

Astronomers have found the best evidence yet of matter spiraling outward from a young, still-forming star in fountain-like jets. Due to the spiral motion, the jets help the star to grow by drawing angular momentum from the surrounding accretion disk.

“Theorists knew that a star has to shed angular momentum as it forms,” said astronomer Qizhou Zhang of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA). “Now, we see evidence to back up the theory.”

Angular momentum is the tendency for a spinning object to continue spinning. It applies to star formation because a star forms at the center of a rotating disk of hydrogen gas. A star grows by gathering material from the disk. However, gas cannot fall inward toward the star until that gas sheds its excess angular momentum.

As hydrogen nears the star, a fraction of the gas is ejected outward perpendicular to the disk in opposite directions, like water from a fire hose, in a bipolar jet. If the gas spirals around the axis of the jet, then it will carry angular momentum with it away from the star.

Using the Submillimeter Array (SMA), an international team of astronomers observed an object called Herbig-Haro (HH) 211, located about 1,000 light-years away in the constellation Perseus. HH 211 is a bipolar jet traveling through interstellar space at supersonic speeds. The central protostar is about 20,000 years old with a mass only six percent the mass of our Sun. It eventually will grow into a star like the Sun.

The astronomers found clear evidence for rotation in the bipolar jet. Gas within the jet swirls around at speeds of more than 3,000 miles per hour, while also blasting away from the star at a velocity greater than 200,000 miles per hour.

“HH 211 essentially is a ‘reverse whirlpool.’ Instead of water swirling around and down into a drain, we see gas swirling around and outward,” explained Zhang.

In the future, the team plans to take a closer, more detailed look at HH 211. They also hope to observe additional protostar-jet systems.

“These are intrinsically difficult measurements. We need narrow jets to be able to detect signs of rotation, and they have to be close enough for us to observe them with high resolution,” said CfA astronomer Tyler Bourke. “There are very few jets around that meet those criteria.”

The technological capabilities of the SMA were crucial in gathering these data.

“The SMA has been in operation since the end of 2003. It has hit its scientific stride and is producing a substantial amount of high-quality scientific results,” said SMA director Ray Blundell.

In the more distant future, new ground-based observatories will turn their powerful gaze on this and other newborn stars.

ASIAA Director Paul Ho notes, “A much more powerful radio interferometer, the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA), is now under construction in northern Chile, as a much more powerful version of the SMA. It will allow us to zoom in to these stellar birthplaces with much finer details and unravel the process of stellar birth directly.”

A paper on this work was published in the December 1 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.