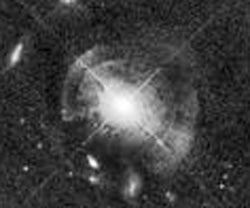

What has appeared as a mild-mannered elliptical galaxy in previous studies is revealing its wild side in new images taken with NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. The Hubble photos show shells of stars around a bright quasar, known as MC2 1635+119, which dominates the center of the galaxy. The shells’ presence indicates a titanic clash with another galaxy in the recent past.

The new Hubble observations reveal at least five inner shells and additional debris traveling away from the galaxy’s center. The shells, which sparkle with stars, resemble ripples forming in a pond when a stone is tossed in. They formed when tidal forces shred a galaxy during collision. Some of the galaxy’s stars were swept up in the elliptical galaxy’s gravitational field, creating the outward-moving shells. The farthest shell is about 40,000 light-years away from the center.

“This is the most spectacular shell galaxy seen at this distance,” said team member Francois Schweizer of the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, California.

The collision also is funneling gas into the galaxy’s center and is feeding a supermassive black hole. The accretion onto the black hole is the source of the quasar’s energy. This observation supports the idea that at least some quasars are born from interactions between galaxies.

“This observation is providing more evidence that mergers are crucial for triggering quasars,” said Gabriela Canalizo of the University of California, Riverside, who led the study. “Most quasars were active in the early universe, which was smaller, so galaxies collided more frequently.

“Astronomers have long speculated that quasars are fueled by interactions that bring an inflow of gas to the black holes in the centers of galaxies. Since this quasar is relatively nearby, about 2 billion light-years away, it is a great laboratory for studying how more distant quasars are turned on.”

Previous studies of this galaxy with ground-based telescopes showed a normal-looking elliptical containing an older population of stars. It took the razor-sharp vision of Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys and the spectroscopic acuity of the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii to uncover the faint, thin shells.

The shell stars are mixing with the stars in the galaxy as they travel outward. Eventually, the shells will dissipate and the stars will be scattered throughout the galaxy.

“This could be a transitory phase, common to most ellipticals, that lasts only 100 million to a billion years,” Canalizo said. “So, seeing these shells tells us that the encounter occurred in the relatively recent past. Hubble caught the shells at the right time.”

Canalizo and her team have not determined the type of merger responsible for the shells and the quasar activity. Their evidence points to two possible collision scenarios.

“The shells’ formation and the current quasar activity may have been triggered by an interaction between two large galaxies or between a large galaxy and a smaller galaxy,” explained team member Nicola Bennert of the University of California, Riverside. “We need high-resolution spectroscopic observations of the quasar host galaxy to determine the type of merger.”