A team of scientists has been combing through the spacecraft’s aerogel and aluminum foil dust collectors since Stardust returned in 2006.The seven particles probably came from outside our solar system, perhaps created in a supernova explosion millions of years ago and altered by exposure to the extreme space environment. The particles would be the first confirmed samples of contemporary interstellar dust.

“These are the most challenging objects we will ever have in the lab for study, and it is a triumph that we have made as much progress in their analysis as we have,” said Michael Zolensky from NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

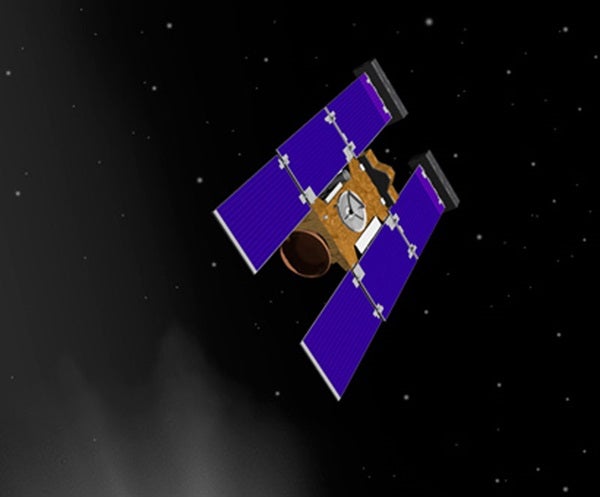

Stardust was launched in 1999 and returned to Earth on January 15, 2006, at the Utah Test and Training Range, 80 miles (130 kilometers) west of Salt Lake City. The Stardust Sample Return Canister was transported to a curatorial facility at Johnson where the Stardust collectors remain preserved and protected for scientific study.

Inside the canister, a tennis racket-like sample collector tray captured the particles in silica aerogel as the spacecraft flew within 149 miles (240km ) of a comet in January 2004. An opposite side of the tray holds interstellar dust particles captured by the spacecraft during its seven-year, 3-billion-mile (5 billion km) journey.

Scientists caution that additional tests must be done before they can say definitively that these are pieces of debris from interstellar space. But if they are, the particles could help explain the origin and evolution of interstellar dust.

The particles are much more diverse in terms of chemical composition and structure than scientists expected. The smaller particles differ greatly from the larger ones and appear to have varying histories. Many of the larger particles have been described as having a fluffy structure, similar to a snowflake.

Two particles, each only about 2 micrometers in diameter, were isolated after their tracks were discovered by a group of citizen scientists. These volunteers, who call themselves “Dusters,” scanned more than a million images as part of a University of California, Berkeley, citizen-science project, which proved critical to finding these needles in a haystack.

A third track, following the direction of the wind during flight, was left by a particle that apparently was moving so fast — more than 10 miles per second (15 km/s) — that it vaporized. Volunteers identified tracks left by another 29 particles that were determined to have been kicked out of the spacecraft into the collectors.

Four of the particles reported were found in aluminum foils between tiles on the collector tray. Although the foils were not originally planned as dust collection surfaces, an international team led by physicist Rhonda Stroud of the Naval Research Laboratory searched the foils and identified four pits lined with material composed of elements that fit the profile of interstellar dust particles.

Three of these four particles, just a few tenths of a micrometer across, contained sulfur compounds, which some astronomers have argued do not occur in interstellar dust. A preliminary examination team plans to continue analysis of the remaining 95 percent of the foils to possibly find enough particles to understand the variety and origins of interstellar dust.

Supernovae, red giants, and other evolved stars produce interstellar dust and generate heavy elements like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen necessary for life. Two particles, dubbed Orion and Hylabrook, will undergo further tests to determine their oxygen isotope quantities, which could provide even stronger evidence for their extrasolar origin.

Scientists at Johnson have scanned half the panels at various depths and turned these scans into movies, which were then posted online where the Dusters could access the footage to search for particle tracks.

Once several Dusters tag a likely track, Andrew Westphal and his team verify the identifications. In the 1 million frames scanned so far, each a half-millimeter square, Dusters have found 69 tracks, while Westphal has found two. Thirty-one of these were extracted along with surrounding aerogel by scientists at Johnson and shipped to University of California, Berkeley, to be analyzed.