In our galaxy, we are used to the idea that even the nearest stars are light-years away from the Sun. But a team of scientists led by Pavel Kroupa of the University of Bonn, in Germany, thinks things were very different in the early universe. In particular, Ultra Compact Dwarf galaxies (UCDs), a recently discovered class of object, may have had stars packed together a thousand times more closely than in the solar neighborhood, according to calculations made by team member Joerg Dabringhausen.

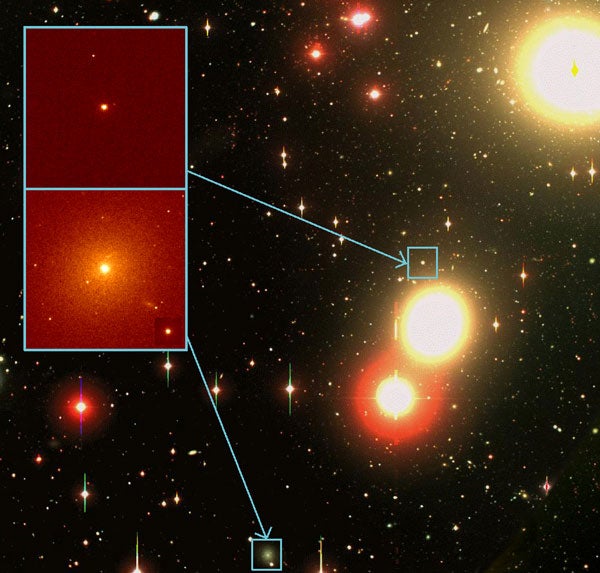

UCDs were discovered in 1999. They are less than 1/1000th the diameter of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. Astronomers believe UCDs were created when galaxies collided in the early universe. But oddly, UCDs clearly have more mass than the light from the stars they contain would imply.

Up to now, exotic dark matter has been suggested to explain this ‘missing mass,’ but this is not thought to gather in sufficient quantities within a UCD. In their paper, Dabringhausen, Kroupa, and Holger Baumgardt present a different explanation.

The astronomers think that at one time, each UCD had an incredibly high density of stars, with perhaps 1 million in each cubic-light year of space, compared with the one that we see in the region of space around the Sun. These stars would have been close enough to merge from time to time, creating many more massive stars in their place. These more massive stars consume hydrogen (their nuclear fuel) much more rapidly, before ending their lives in violent supernova explosions. All that remains is either a super dense neutron star or sometimes a black hole.

So in today’s UCDs, a good part of their mass is made up of these dark remnants, largely invisible to Earth-based telescopes but fossils of a more dramatic past.

Dabringhausen said, “Billions of years ago, UCDs must have been extraordinary. To have such a vast number of stars packed closely together is quite unlike anything we see today. An observer on a (hypothetical) planet inside a UCD would have seen a night sky as bright as day on Earth.”